Text : Eric Shanes

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78160-617-9

Andy

Warhol

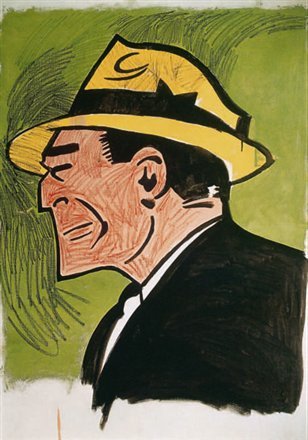

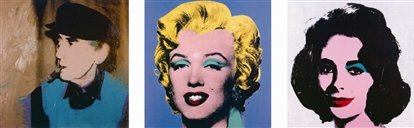

1. Dick Tracy, 1960.

Casein and pencil on canvas, 121.9 x 83.9 cm.

The Brant Foundation, Greenwich.

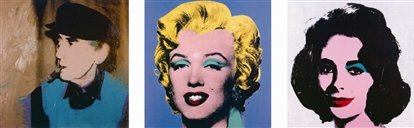

Andy Warhol was an artist who undoubtedly put his finger on the pulse of modern culture. Through pioneering a variety of techniques, but principally by means of the visual isolation of imagery, its repetition and enforced similarity to printed images, and the use of garish colour to denote the visual garishness that is often encountered in mass culture, he threw much direct or indirect light upon modern anomie or world-weariness, nihilism, materialism, political manipulation, economic exploitation, conspicuous consumption, media hero-worship, and the creation of artificially-induced needs and aspirations. Moreover, in his best paintings and prints he was a very fine creator of images, with a superb colour sense and a brilliant feel for the visual rhythm of a picture which resulted from his intense awareness of the pictorial potentialities inherent to forms. Initially, his images might appear rather simple. Yet because of that very simplicity they not only enjoy a high degree of immediate visual impact, but also possess the rare power of projecting huge implications through the mental associations they set in motion. For example, the visual repetitiousness that Warhol employed within a great many of his images was intended associatively to parallel the vast repetitiousness of images that is employed in a mass-culture in order to sell goods and services including vehicles of communication such as movies and TV programmes whilst by incorporating into his images the very techniques of mass production that are central to a modern industrial society, Warhol directly mirrored larger cultural uses and abuses, while emphasizing to the point of absurdity the complete detachment from emotional commitment that he saw everywhere around him. Moreover, as well as employing imagery derived from popular culture in order to offer a critique of contemporary society, Warhol also carried forward the assaults on art and bourgeois values that the Dadaists had earlier pioneered, so that by manipulating images and the public persona of the artist he became able to throw back in our faces the contradictions and superficialities of contemporary art and culture. And ultimately it is the trenchancy of his cultural critique, as well as the vivaciousness with which he imbued it, that will surely lend his works their continuing relevance long after the particular objects he represented such as Campbells Soup Cans and Coca-Cola bottles have perhaps become technologically outmoded, or the outstanding people he depicted, such as Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley and Mao Tse-Tung, have come to be regarded merely as the superstars of yesteryear.

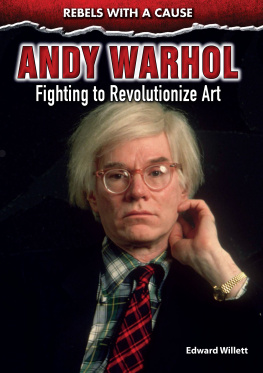

Andy Warhol was born Andrew Warhola on 6 August 1928 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the third son of Ondrej and Julia Warhola. They were immigrants from what is today the Slovak Republic but which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After leaving school in 1945, Warhol attended the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, majoring in Pictorial Design, where he received an excellently rounded art education.

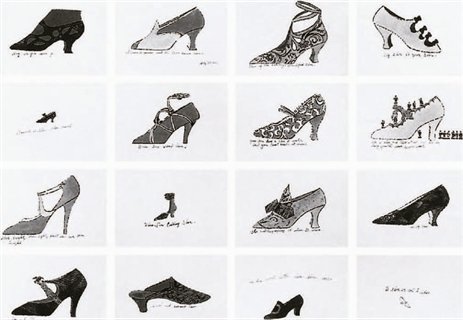

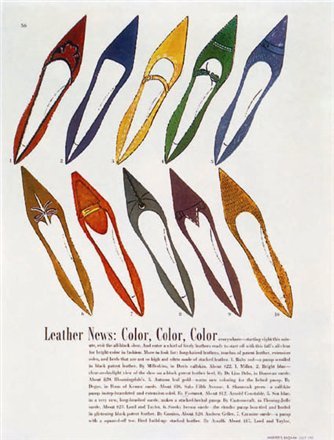

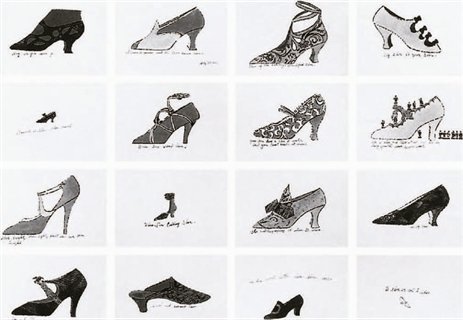

2. A la Recherche du Shoe Perdu, 1955.

Lithograph watercolour, each 24.5 x 34.5 cm.

The Andy Warhol Foundation for

the Visual Arts, Inc., New York.

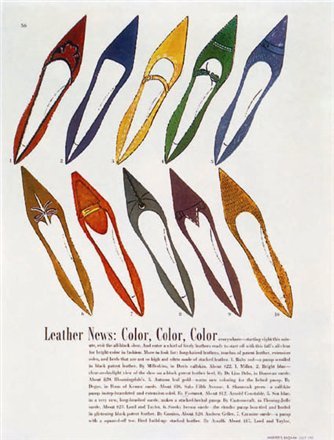

3. Shoe Advertisement for I. Miller, 1958.

The Andy Warhol Foundation for

the Visual Arts, Inc., New York.

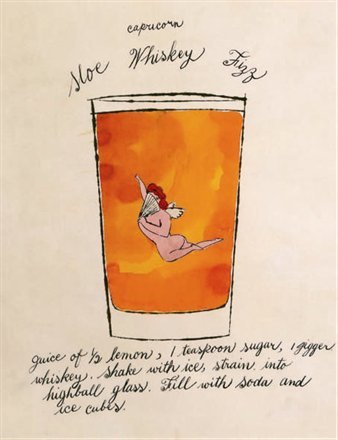

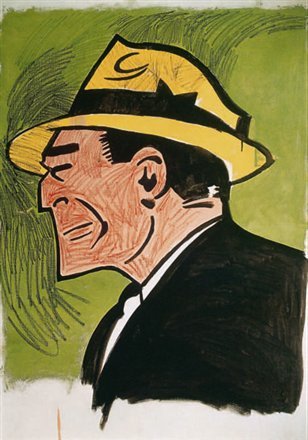

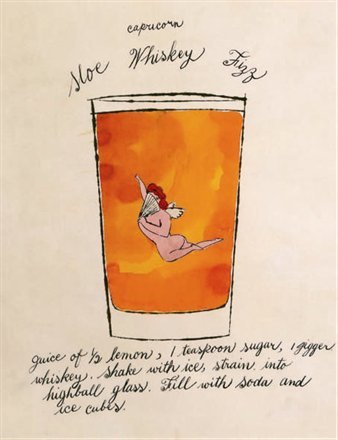

4. Capricorn Sloe Whiskey Fizz, 1959.

Draw by ink on paper, coloured with

the hand, 60.3 x 45.7 cm.

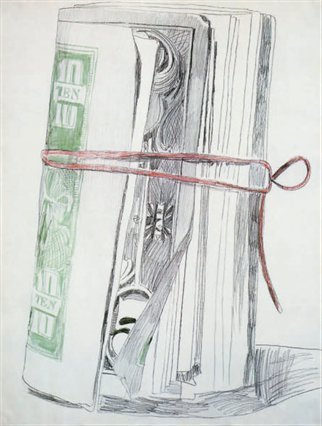

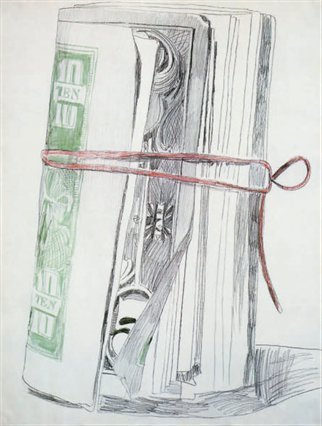

5. Roll of Bills, 1962.

Pencil, felt-tipped pen and

crayon on paper, 101.6 x 76.4 cm.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

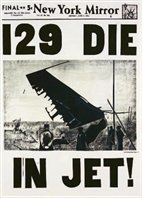

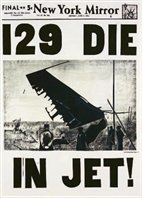

6. 129 Die in Jet (Plane Crash), 1962.

Acrylic paint on canvas, 254 x 183 cm.

Museum Ludwig, Cologne.

In the spring of 1948 Warhol obtained a degree of professional design practice by working part-time in the art department of the largest department store in Pittsburgh. In June 1949 he graduated from the Carnegie Institute with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree. The following month he moved to New York where he soon made the acquaintance of Tina Fredericks, the art editor of Glamour fashion magazine. She commissioned a suite of shoe illustrations, shoes being a subject that Warhol would soon make his speciality. When these illustrations appeared in the magazine in September 1949, the a in Warhols surname was dropped from the credit byline (possibly by accident) and the artist adopted that spelling thereafter.

Warhol was determined to succeed in New York and he haunted the offices of art directors in search of work, even cultivating a down-and-out, raggedy Andy look in order to gain the sympathy of potential clients. One successful commission soon led to another, and within a relatively short time Warhol was much in demand for his highly characterful illustrations, both within the Cond Nast organisation (to which Glamour magazine belonged) and beyond it. Warhol was extremely accommodating as far as all his employers were concerned, for as he related in 1963:

I was getting paid for it, and did anything they told me to do. If they told me to draw a shoe, Id do it, and if they told me to correct it I would Id do anything they told me to do, correct it and do it right after all that correction, those commercial drawings would have feelings, they would have a style. The attitude of those who hired me had feeling or something [near] to it; they knew what they wanted, they insisted; sometimes they got very emotional. The process of doing work in commercial art was machine-like, but the attitude had feeling to it.

In September 1951 one of his drawings that was reproduced as a full page advertisement in the

Next page