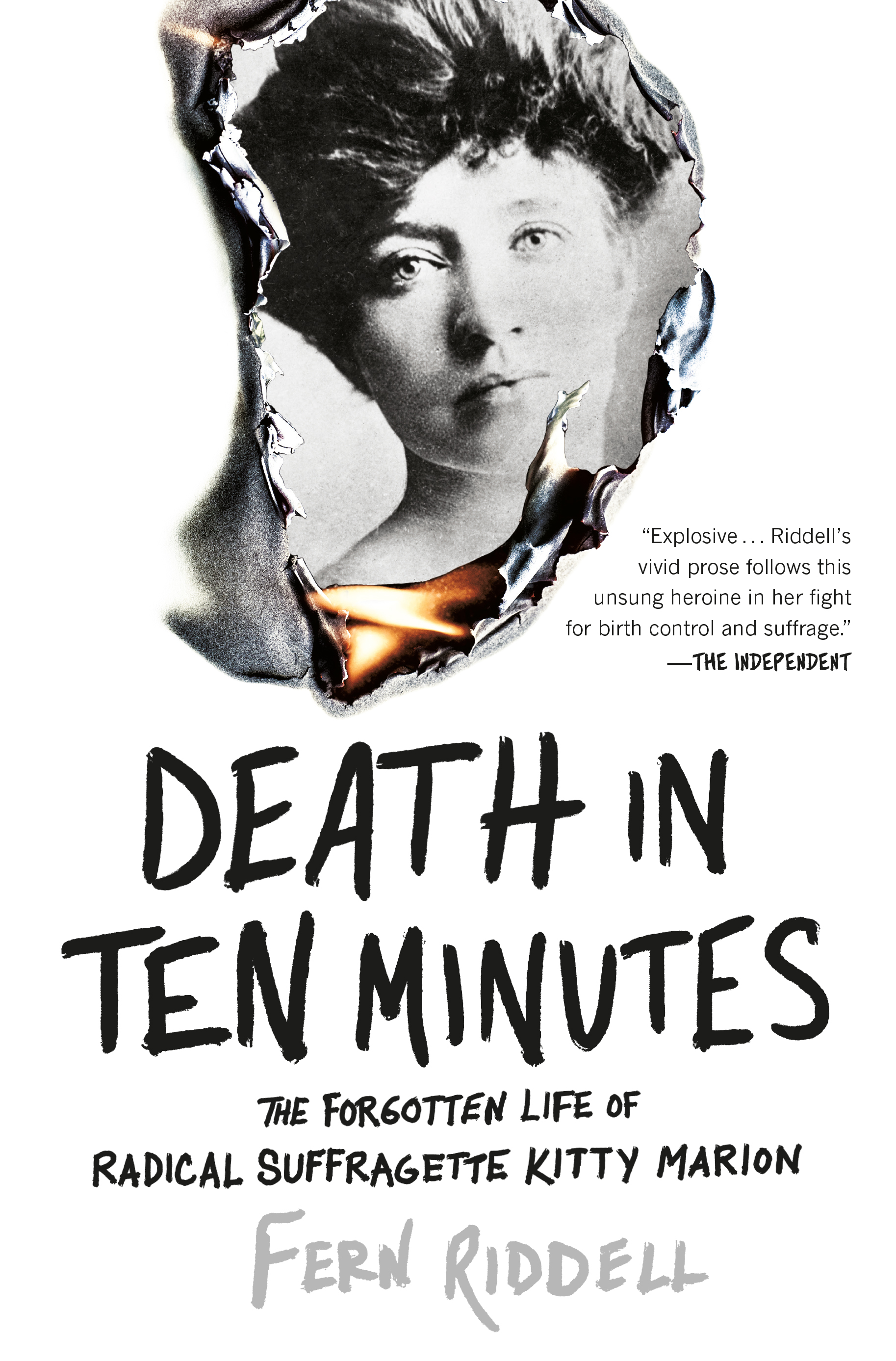

Death in Ten Minutes

Also by Fern Riddell

The Victorian Guide to Sex: Desire and Deviance in the 19th Century

New York London

2018 by Fern Riddell

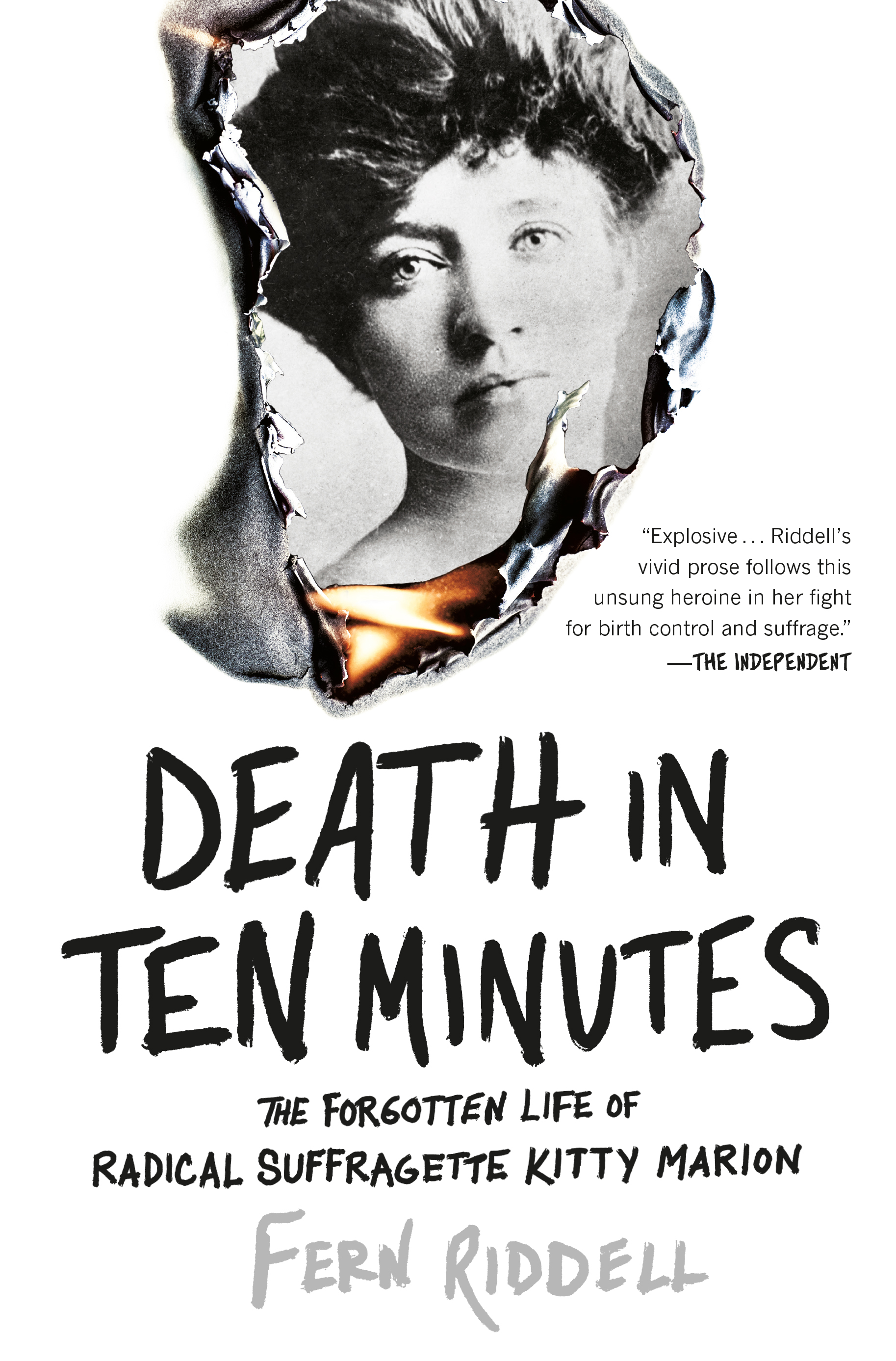

Jacket design by Brian Lemus

Jacket imagery Tom Biegalski/Shutterstock (fire) and Mary Evans/ The National Archives, London, England (Kitty Marion)

First published in the United States by Quercus in 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to .

e-ISBN 978-1-63-506131-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file.

Distributed in the United States and Canada by

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

www.quercus.com

For Kitty

Contents

Imagine we have spent the day at the National Portrait Gallery, among the paintings of figures and images from history. Our clothes are heavy, our feet are tired, and we leave the airless relics of the past to step out into the crisp London air. Facing Trafalgar Square, you see a woman standing on the plinth between two lions; her voice carries on the breeze toward us, and we catch snatches of her words. Moving closer, we are caught in a crowd that pushes and pulls like a tidal wave, barely kept in check by the police officers who dart in and out of the throng, removing men and women who fight and kick, eager to hear this diminutive figure speak. A line of policemen guard her feet, holding back the crowd from the edge of where she stands, to make room for the journalists, elbow to elbow, who furiously scribble down her words on their paper pads for the next edition.

As we push our way through this vocal congregation and move along toward the bustling street of the Strand, a woman catches your eye. She is Indian, the goddaughter of Queen Victoria, and stands, ferocious, on the corner selling copies of a magazine written by the organization led by the woman on the platform. She wears a sash of purple, green, and white. Perhaps we stop and speak to her, perhaps we move quickly past, but within a few hundred feet another woman, with the same sash and the same fierce, daring stare, stands in our way. She wears a placard over her chest announcing a new and exciting matinee just around the corner. There is a political play about the rights of women being shown, and a queue is already forming. Suddenly, a deep boom sounds from the direction of St. Pauls, and frightened birds fill the air. A man struggles to keep control of his carthorse as a growing surge of people rush past, shouting, A bomb! A bomb! They put a bomb in St. Pauls!

This is 1913, and it is the time of the suffragettes.

Here, sneaking through the Mancunian twilight, is Kitty Marion, music hall star and militant suffragette, disguising her red hair under a mill girls shawl. She makes her way through Alexandra Park toward the glasshouse, where she leaves a pipe bomb primed to explode in the early morning. This is not her first attack, nor will it be her last, as she is a member of the Womens Social and Political Union (WSPU)a soldier in the war raging across Britain, and the world, to give women the vote. Kitty Marion and the many women like her are part of a violently radical and dedicated branch of the suffrage movement, which conducted a nationwide campaign of terror that has never been truly acknowledged in our history before.

At half past four in the morning, on Tuesday, November 11, 1913, the cactus house in Manchesters Alexandra Park was reduced to rubble by a stout brass tube, about three inches in diameter, and strengthened at one end by a stout brass cap, which was screwed on to it. The Leeds Mercury pored over every detail of the device, as police began a frantic hunt for the person or persons unknown who could carry out such violence.... [T]he brass cap had been bored for the insertion of the fuse. The tube was about fifteen inches long, and in addition to a heavy charge of powder it contained a miscellaneous collection of pieces of To those picking through the debris it was clear the force of the explosion had scattered the contents of the bomb over a wide area, far from the twisted ruins of the cactus house itself.

Manchester had suffered an earlier attack by the suffragettes in April. Annie Briggs, Evelyn Manesta, and Lillian Forrester attacked numerous paintings in the Manchester Art Gallery, seizing the opportunity to smash the glass coverings of Frederic Leightons The Last Watch of Hero and Sibylla Delphica by Edward Burne-Jones as the museum began to close at 9:00 p.m. As the attackor outrage, as the press often called themtook place, supporters of the womens movement had unfurled a Votes For Women banner in the gallery, fighting off the attendants who attempted to wrestle them into submission and tear the banner down.

The April attack was not unique. Organized in a wave of retaliation to the sentencing of the WSPUs leaderthe fifty-four-year-old Moss Side native Emmeline Pankhurstto three years in jail after she had admitted to inciting persons unknown to bomb the holiday cottage of the chancellor of the exchequer, David Lloyd Georgenumerous attacks were now taking place across the country. These suffragette outrages grew in violence and intensity in the years before the First World War, ranging from window-breaking, chemical attacks on mailboxes, and the cutting of telegraph and telephone wires, to the arson and bombings of churches, railway carriages and stations, MPs homes, racecourses, golf courses, sporting pavilions, theaters, public parks, banks, newspaper offices, and museums. Anywhere you could find a woman, you could find a suffragette bomb. And yet we know so little about the women operating on this self-declared danger duty. Why did they choose such extreme and violent action to make a political protest? What had happened to them that led to their decision to leave a bomb in a public place? Today, we find such actions morally repugnant, the tools of outsiders and organizations whose values deeply contradict our own. So how do we feel when we discover these actions in a movement we idolize? Is there room for our heroes to be flawed?

The Manchester attack, along with the many others Kitty Marion carried out on behalf of the WSPU, has long been hidden from our acknowledged history of the fight for the vote. But Kitty kept her own record, an unpublished autobiography detailing her life and actions as a suffragette and birth control activist, as she fought for respect and equality for women in all areas of their lives. Her unique story shines a light on the previously ignored actions of many involved in the womens movement, and shows us that they committed to a plan of action that violently contradicted their supposed place in society, and the rules of men.

Next page