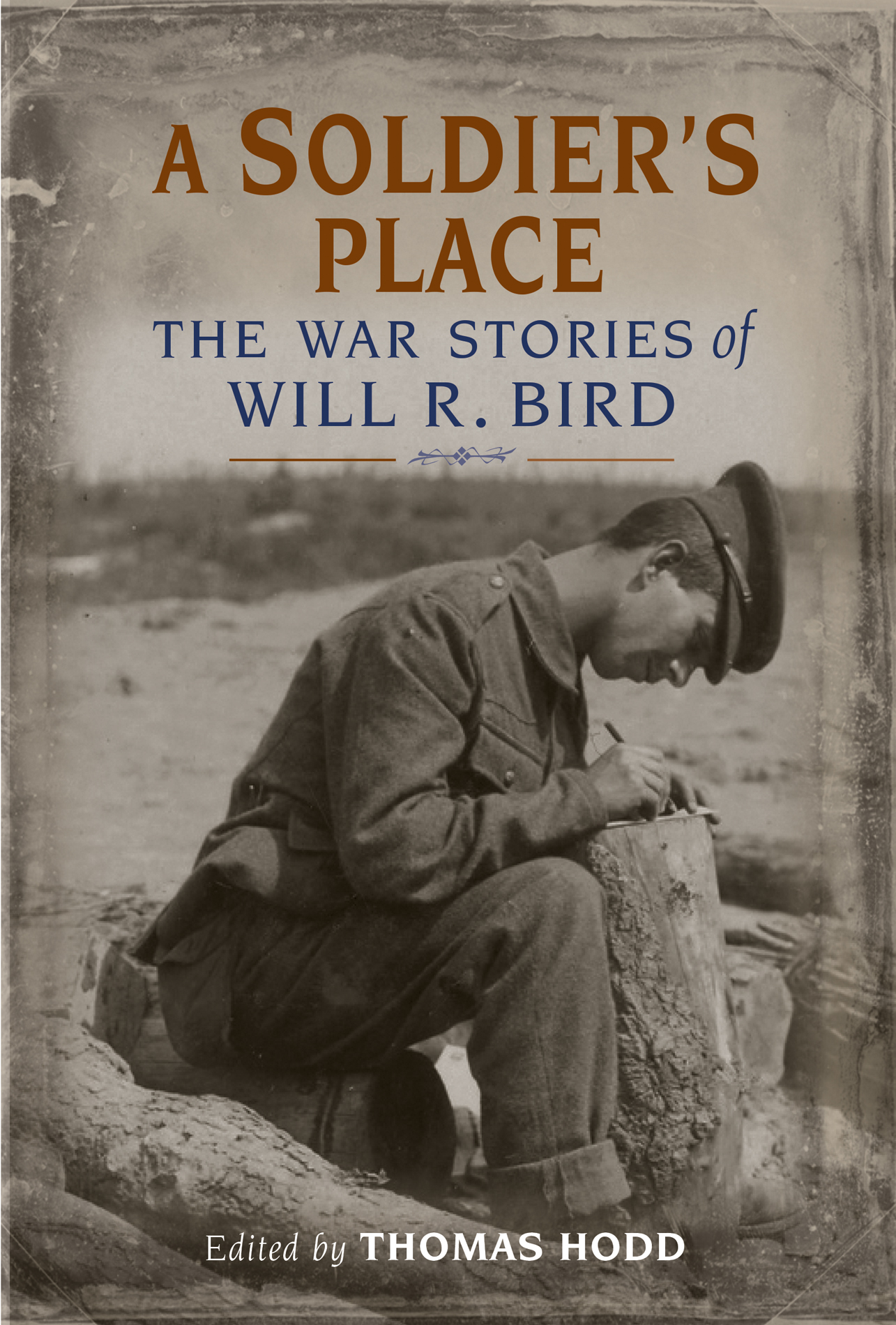

To Master Warrant Officer Daniel Joseph Hodd, and to all the soldiers who struggle to tell their stories

Introduction

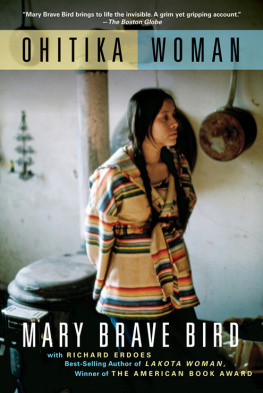

T rench-fighter, military medallist, and the unofficial Bard of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, according to historian Jonathan Vance, Will R. Bird (18911984) dedicated much of his life to storytelling. Over a writing career that spanned more than five decades, the Nova Scotia-born author amassed a store of travel pieces, short stories, novels, edited books, and other works of non-fiction that number in the hundreds. He published more than a dozen novels, as well as a history of Nova Scotia. He also wrote two memoirs, a handful of poems, and several dramatic pieces. But what many Canadians dont know is that a large portion of these publications were inspired by Birds experience as a combat soldier during the First World War. Whats more, had it not been for a belief in the supernatural he might never have seen action at all, let alone wrote about it.

Born in East Mapleton, near Amherst, Nova Scotia, Birds early years were marred by emotional and financial hardship: his father died when Bird was four years old; he was also forced to leave school in grade eight to help support his family, before moving out west a few years later. To make matters worse, while his friends and even his youngest brother, Stephen, had been able to join the war effort, Bird had been rejected twice due to medical reasons. Then, in 1915, while working in a field in Saskatchewan he saw an apparition of his brother:

I was [] pitching sheaves on a wagon, when Steve walked around the cart and confronted me. He said not a word but I knew all as if he had spoken, for he had on his equipment and was carrying his rifle. I let the fork fall to the ground and the nearest man came running to me, thinking I had taken ill. I did not tell him what I had seen, but I left the field, and never pitched another sheaf of grain. All that day, and the next, and the next, I wandered by myself around the prairie, and then the message came, a wire, Steve has been killed. Come home. (And We Go On, 89.)

Bird returned to Nova Scotia and tried again to enlist. This time he was successful, and was assigned to the 193rd Battalion, the Nova Scotia Highlanders, although he was eventually transferred to the 42nd Battalion to serve out the remainder of the war with the Black Watch. He first saw action in the fall of 1916, and spent a short time as a sniper before turning patrolman. He also took part in some of the most important battles of the First World War, fighting at Passchendaele and Amiens, as well as at Arras and Cambrai. Remarkably, he survived the war with no lasting physical injuries, an impressive feat for an infantryman. He was even awarded a Military Medal for Bravery at Mons, Belgium, on the final day of the war.

After being demobilized, Bird moved back to Nova Scotia and, for a brief time, ran a general store before having to close shop and take a job at the local post office. Then in the early 1920s, he entered his first writing contest and won, which inspired him to begin sending out his stories for publication. Success soon followed. He decided to try his hand at writing full time, but in order to do so he needed to find a subject that would interest readers. Luckily for Bird, very few veterans wanted to write downor even talk abouttheir experiences in the trenches, so he made it his mission to tell their stories.

The result? No Canadian author who served overseas has published more on the First World War than Will R. Bird. Although a handful of his contemporaries, such as Prince Edward Island native Basil King and Ontario writer Ralph Connor, each published maybe a handful of novels on the subject, during the early 1930s the Great War became almost an obsession for Bird: he penned no fewer than five books on the subject as well as numerous short stories and other non-fiction pieces. His main non-fiction works include Thirteen Years After: The Story of the Old Front Revisited (1932) and The Communication Trench (1933). He also wrote a novel, Private Timothy Fergus Clancy (1930). His most lasting book from this period, however, is his soldier memoir, And We Go On (1930), recently republished with McGill-Queens University Press. It has become a staple for Canadian military historians and to those interested in reading about the soldier experience during the First World War.

But a memoir about the soldier experience does not capture the imagination in the same way that a novel or short story might. Equally curious, the majority of Canadian fictional responses to the First World War published during and after the conflict tended to be novels, not short stories. So once again Bird chose the road less travelled: beginning in the late 1920s and continuing for the next two decades, he published more than fifty war stories. His tales of courage, survival, and self-doubt eventually appeared in a variety of publications and trade magazines, including Macleans, Colliers, the Toronto Star Weekly, and the Maritime Advocate and Busy East. Most of Birds war stories, however, first found a home in one of three literary outlets: the Legionary, a magazine launched in May 1926 and meant almost exclusively for military veterans; the short-lived New York pulp magazine War Stories; and the Canadian pulp periodical, Canadian War Stories, published out of Chatham, Ontario, but which lasted less than a year. The majority of these publications are no longer in print, nor are they digitized. So for the last several decades Will Birds extraordinary tales of war have fallen ever deeper into Canadian literary obscurity.