Suddenly the scene was thrown into relief by a flash brighter than the sun. An immense cloud of smoke shot up into the air above Halifax crowned by an angry, crimson ball of rolling flames. Almost at once the flames were swallowed up in the black-grey smoke but from time to time they reappeared, boiling in its midst.

The billowing mass rolled higher and higher and then, after a few seconds, Campbell heard two thundering reports in quick succession.

The captains sextant lay near at hand and, grabbing it, he took an observation of the summit of the smoke, now flattened and spreading outwards. His rapid calculations showed that it had risen to more than 12,000 feet.

Fifteen minutes later the vast cloud was still visible. Now it hung, almost motionless, like an open umbrella over the funeral pyre of the town that died.

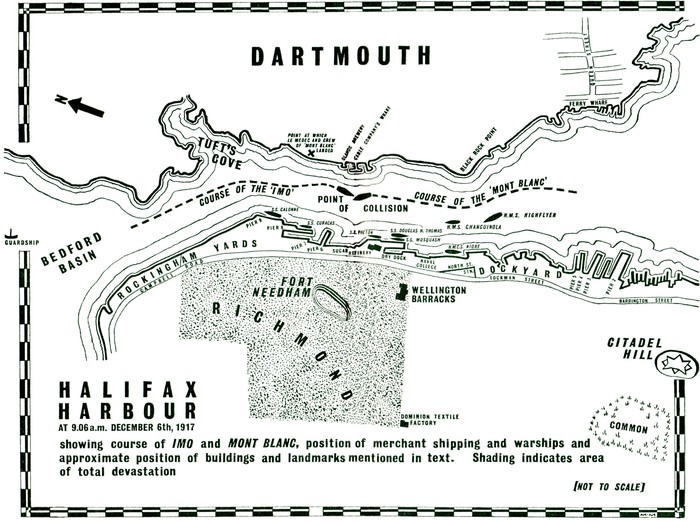

A LITTLE after one oclock on Wednesday, 5 December, 1917, Captain Aim Le Medec entered the wheelhouse of the French freighter MontBlanc. He had just worked out the ships position as at one precisely and now he checked the compass before the helmsman. He nodded his satisfaction at the bearing to First Officer Jean Glotin and then went out onto the bridge.

The French ship had cleared New York at 11 p.m. on 1 December and from that moment Le Medec, fearfully conscious of the possibility of a marauding U-boat, had run as close inshore as he dared. From Newport to Bar Harbour the MontBlanc had hugged the American coast. Off Bar Harbour, however, he had been forced to leave these comparatively safe waters and to head his vessel out into the open sea for a landfall at Yarmouth.

The one hundred mile crossing of the mouth of the Bay of Fundy had been tense but uneventful and now, away to port, the flat and rocky coast of Nova Scotia continued to offer further sanctuary.

The MontBlanc was steaming at full speed some nine miles south-west of Pennant Point. In another hour or so she would round Cape Sambro and from there Le Medec would make for the examination anchorage between Lighthouse Bank and McNabs Island in accordance with the instructions given to him on sailing. Once in the anchorage, with formalities concluded and a pilot aboard, the MontBlanc would proceed up-channel into Halifax Harbour.

Through the windows of the wheelhouse helmsman Marcel Aleton momentarily allowed his attention to wander. Idly he watched the captain as Le Medec slowly paced the bridge, deep in thought. He is a worried man, our Commandant, Aleton was later to report to other members of the crew, and who can blame him with such a cargo as ours in this bloody old hulk?

Aletons was a fair enough general description of the condition of the MontBlanc for the small, 3,121-ton freighter had been badly used and hard worked during her sea time, but she was certainly not nearly as old as many another and prouder ship then in service.

Built by Sir Raylton Dixon & Company in their Middlesbrough shipyard, she had been launched in 1899 and purchased by E. Anquetil of Rouen who had held her for charter to all comers and for every type of cargo. Giddy with the profits to be made during the transportation boom of the early years of this century, Anquetil, who would concede only the most vital repairs and who had provided the minimum amount of maintenance, had pushed his ship to the very limits of safety and sea-worthiness.

It was then an already tired and neglected MontBlanc that the reputable Compagnie Gnrale Transatlantique bought in 1915. It is doubtful whether at any other time they would have considered adding such a vessel to their well-known fleet but the urgent need for any and all ships to counter-balance the heavy toll levied by U-boats against the Allied merchant marine gave them no alternative. So it was that patched, painted and overhauled as thoroughly as possible and with St. Nazaire as her new port of registry, and with a light gun mounted forward and another aft, the MontBlanc went to war.

During the 191418 hostilities all French merchant ships above a certain tonnage and of sizeable capacity came under the control of the French Admiralty. This was achieved not by requisition of the vessels themselves, but indirectly by a Government order mobilising all merchant marine officers into the Naval Reserve. Therefore, whilst the MontBlanc was, on paper, operated by her new owners she came under Navy orders as to the cargoes she carried and movement control, and almost immediately upon acquisition by the Compagnie Gnrale Transatlantique she was put into active service.

For many months, following the United States declaration of war on Germany on 6 April, 1917, she sailed the Atlantic uneventfully, carrying on her outward journeys general cargo for North America and returning to Europe laden with vital raw materials for the French war effort. When, however, on 25 November, 1917, she berthed in Gravesend Bay, New York, there was a more sinister shipment awaiting her and on this voyage the MontBlanc had a new master.

Not more than 5 feet 4 inches in height but well built, with a neatly trimmed black beard to add authority to his somewhat youthful face and with, as a Canadian newspaper man was later to report, a broad forehead over snapping dark eyes, Captain Aim Le Medec was thirty-eight years old when he assumed command and joined the ship at Bordeaux. To back his appointment he had more than twenty-two years experience of the sea and he had seen over eleven years service with the Compagnie Gnrale Transatlantique . On the summary of his service notes, kept in the records of their Paris office, it is constantly emphasised that he was of a serious and modest character with remarkable qualities as an active and conscientious officer. A contemporary, however, describes him as a likeable but moody man at times inclined to be truculent and as a competent, rather than a brilliant, sailor.

Nevertheless Le Medecs steady promotion had followed the normal pattern of an officer in whom his employers had every confidence. From second officer when he joined the Company at twenty-seven in 1906, he had risen through first officer to captain by 1916 when he was given the Antilles. The following year, but for a brief period only, he was master of the Adb-el-Kader.

Immediately upon his appointment to the MontBlanc he had impressed upon her four officers his intention of working strictly to the book and had set about tightening discipline and improving efficiency among the thirty-six men of her mixed French and French Colonial crew.

At first resentful of his demands upon them the men quickly came to respect and trust their captain and Le Medec was reasonably happy with his new command when his ship tied up in Gravesend Bay. True the misused MontBlanc was no great prize to an ambitious young officer but he accepted her as one further step up the ladder of his career, confident in his ability as a seaman, equal to any hazard of his profession in peace or war.