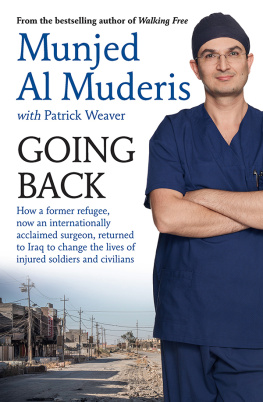

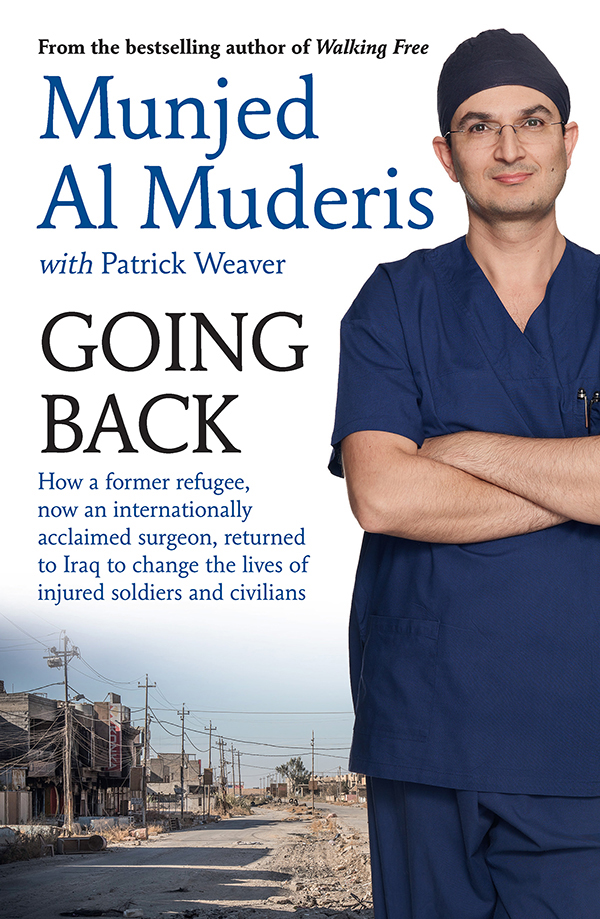

First published in 2019

Copyright Munjed Al Muderis and Patrick Weaver 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76063 316 5

eISBN 978 1 76087 071 3

Uncredited photographs courtesy of Claudia Roberts, Michelle Nairne and Patrick Weaver

Set by Post Pre-press Group, Australia

Cover design: Romina Panetta

Cover photography: Lucas Allen (Munjed Al Muderis); iStockphoto (Qaraqosh, Iraq)

A chill ran down my spine as the Qatar Airways Boeing 737 descended and, through the darkness, the lights of Baghdad gradually came into sight in the distance. Oh no, what have I done? I thought. Im coming back to the place I escaped nearly two decades ago. The city where I came so close to being executed. I went through a succession of traumatic experiences to get out. Now, of my own free will, Im here again. It doesnt make any sense at all!

My return to Iraq in 2017 was an entirely unpredictable and surreal experience. I felt completely remote from the events that were unfolding, like I was watching someone elses story.

After eighteen years, so much had changed. First and foremost, I had established my new life in Australia. And my feelings as we approached the tarmac at Baghdad International Airport reinforced the fact that these days I am passionately Australian and proudly regard Australia as my home. Its where I created my orthopaedic practice and where the closest members of my family live.

Sure, I have maintained contact with the expat Iraqi community in Sydneymainly based in and around what is sometimes known as Little Baghdad, at Fairfield in the southwestern suburbsand Ive kept a keen, often despairing, watch on events in the country where I was born. Who hasnt? Lets face it: Iraq has been in the world headlines for most of the time since I left.

But, as we approached Baghdad, it didnt occur to me that I was coming home. I felt as though I was arriving in a foreign country. I felt like an outsider.

Flight QR 442 from Doha in Qatar had been a circus from the time I queued at the boarding gates with my personal assistant, Michelle Nairne, and my physiotherapist and partner, Claudia Roberts. For a start, we began boarding the plane 90 minutes before the scheduled departure. Its normally half that time. I couldnt figure out why at first. But it gradually became clear when I saw the other passengersthe vast majority of the people queuing nine or ten deep at the gates were pilgrims from rural areas of Iraq who were returning from the annual pilgrimage to Mecca, known as Haj. Most of them seemed completely unfamiliar with air travel and what to do at an airport. The journey to and from Mecca was probably the first time many of them had been on a plane.

Muslims from regional Iraq tend to be highly traditional and deeply conservative. They were all dressed in white and every woman was wearing a headscarf. As I looked around the departure hall, I quickly realised that Claudia and Michelle were the only women who werent covered.

This is terrible, I thought. Its not the Iraq I remember from the days when I was growing up.

I was apprehensive and said to my travelling companions, You dont have to go through with this. You can fly back to Sydney from here.

They immediately declined. In fact, both were horrified at the suggestion they should make an early return to Australia. In the previous days, wed been to South Africa and the United Kingdom. But this was the leg of our trip they had most eagerly anticipated.

Claudia looked at the throng of pilgrims and lightheartedly suggested, At least they dont smell! The observation came back to bite us. The truth was that many of the pilgrims did have bad body odour.

Its all part of the more zealous interpretation of Islamic teachings: a woman is committing a sin if a man smells her scent. As a result, they dont wear perfume. And the more religious Muslims take it to the extreme and dont use antiperspirant, either. So, ironically, by adopting the literal view of the teachings, they smell morecompletely defeating the purpose of the edict.

The staff at the boarding gateslargely foreign nationals who didnt speak much Arabicwere particularly rough with the pilgrims as they herded them onto the aircraft. While I dont share the pilgrims religious faith, I believe they deserved to be treated and respected like any other traveller. Watching events unfold, I decided I needed to intervene and had a heated discussion with a female member of the airport staff who was being especially harsh with the pilgrims.

The experience didnt become any easier when we eventually boarded the aircraft. I was concerned for Claudia and Michelle, who were both massively conspicuous because of their uncovered heads. Claudia is also very tall, with long blonde hair. Shed stand out in any crowd in the Middle East.

To avoid potential conflict with any other passengers, I advised them not to talk to anyone. And, if they did have to say anything, not to reveal why we were flying to Iraq.

Of course, the inevitable happened. Within a matter of minutes, someone asked them why they were going to Iraq. Claudia panicked a little, didnt know what to say and blurted out, Were going on holiday!

Going on holiday to Iraq, a nation that, over the decades, had become famous as the most dangerous place on earth? It was hardly a convincing answer. Weve laughed about it many times since.

I edged my way along the aisle of the plane and into my seat, followed by a morbidly obese Iraqi woman who flopped herself down immediately behind me. The flight attendant checked her ticket. Im sorry, but youre in the wrong seat, he told her. You should be in Row 23 in the economy section.

The woman argued back in Arabic, which the flight attendant clearly didnt understand. I have a ticket. Im a big woman, and this is a big seat, she told him.

The flight attendant continued to explain in English that all seating on the plane was allocatedthe passenger couldnt just sit wherever she chose. Meantime, several other passengers also tried to grab a seat in business class, even though theyd only paid for economy. Finally, the leader of their tour group managed to restore some form of order, and the pilgrims were settled into more or less the right seats.

I was dumbfounded by the whole experience and thought, What is going on? Iraq used to be a leader of the developing nations. This is chaos. These people know nothing about how the world works.

The rest of the mercifully short flightit was less than three hourswent relatively smoothly, until the end. As we landed, the cabin crew made the usual announcement. Welcome to Baghdad International Airport. Passengers should remain seated until the Fasten Your Seatbelts sign has been switched off. Even as the announcement was being made, 20 or 30 passengers leapt into the aisle, opened the overhead lockers and started wrestling their bags into the cabin.