Teaching Arabs, Writing Self

First published in 2014 by

OLIVE BRANCH PRESS

An imprint of Interlink Publishing Group, Inc.

46 Crosby Street, Northampton, Massachusetts 01060

www.interlinkbooks.com

Copyright The Estate of Evelyn Shakir, 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shakir, Evelyn, 1938

Teaching Arabs, writing self : memoirs of an American woman / by Evelyn Shakir.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-56656-924-8

1. Shakir, Evelyn, 1938- 2. Shakir, Evelyn, 1938---Travel--Middle East. 3. English teachers--Middle East--Biography. 4. Lebanese American women--Massachusetts--Biography. 5. Lebanese Americans--Massachusetts--Biography. I. Title.

PE64.S43A3 2013

818'.603--dc23

[B]

2013023656

General Editor: Michel Moushabeck

Copyeditor: Kitty Florey

Proofreader: Jennifer M. Staltare

Cover and book design: Pam Fontes-May

Printed and bound in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To request our complete 48-page, full-color catalog, please call us toll free at 1-800-238-LINK, visit our website at www.interlinkbooks.com, or send us an e-mail:

info@interlinkbooks.com

To

My father, Wadie

My mother, Hannah

My brother, Philip

Iconoclasts all

Contents

Preface

In recent years, I have taught American literature to university students in three Arab countries: Lebanon, Syria, and the archipelago kingdom of Bahrain. In Damascus a man asked me how I liked my students. Very much, I said. I learn from them every day.

He shook his head in protest. The eye, he said, calling on an Arab proverb, does not sit above the eyebrow.

Despite his gallantry, he was, of course, mistaken. I did learnhow could I not?from my students as well as from other Syrians, whether friends, shopkeepers, or cabbies. In Lebanon and Bahrain, it was the same.

This two-way street, my teaching others, their teaching me, is reflected in the title of my book. Just as hanging judges hang and kissing cousins kiss, teaching Arabs may teach; think of those pictures where, if you stare at them long enough, foreground and background swap around. The second half of the title performs a similar do-si-do: self both the writer and the written about. And, of course, self and Arab have been brought under a single roof for a reason. Cohabitation implies intimate connection.

Because what took me to Arab lands, initially, was a belated desire to connect with my own heritage. As a child of immigrants from Lebanon, I had tried to run from it. My goal was to be American, and to expunge in myself every trace of foreignness. In those days before wed wrapped our tongues around multiculturalism and diversity, our teachers, the news media, politicians, and pop culture all conspired to promote ethnic amnesia and urge assimilation. I was a good student; I bought it all. If there was a flaw in their definition of American, I couldnt see it. I think the closest I came to suspecting something was amiss was when I would mention the name of one classmate or another to my parents. Oh, they would saylike pulling a rabbit out of a hathes Italian or shes Irish or hes Greek. I began to wonder: So who are the Americans and where are they hanging out? It took years before I could say, with Pogo-like certainty, I have met the Americans and they are us.

Given that personal history, it has made sense to me to divide this book into three sections: one that reflects on my early attempts to sort out my identity (and related family matters); one that explores my teaching abroad; and, finally, one that looks inward again but at a different hour and under a different sky.

I

Childhood

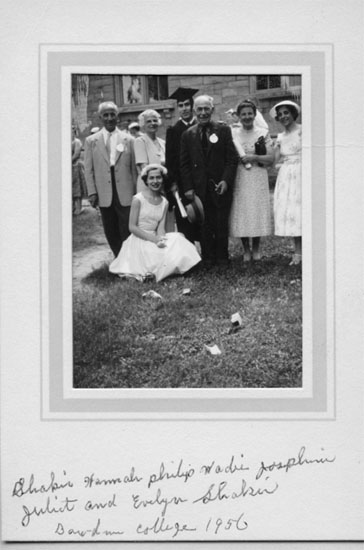

Evelyns graduation from Wellesley College

At Home and Away:

Thirteen Takes on Growing Up Arab in America

Its my experience that Arabs and psychiatrists are natural enemies. One says, Family first. The other says, Only neurotics call home every day. Another difference is that Arabs dont want to hear a word about psychiatry. It hurts their ears. Ooft, they say. Whats this craziness! But psychiatrists are eager to pry into Arab psychesexpecting to find a house of horrors. Each group calls the other bonkers.

My mother and father were immigrants from Lebanon. I was born in the United States. In the eighties, when Americans were being kidnapped in Beirut, a therapist explained to me the source of my unhappiness: Your family is holding you hostage, she said. She was being clever. She was pleased with herself.

My Uncle Yusuf, a gentle man, loved America but hated Catholics, Democrats, and Jews. Mention the pope to him, hed come close to spitting. Jews, of course, were the usurpers, planting themselves on Arab land. Which also explained his venom toward Democrats and Harry Truman, in particular, whod waited all of 11 minutes before saying yes when Jews in Palestine declared themselves a state.

My Uncle Yusuf loved his suburban garden. He grew vegetables for his wife, and flowers for the joy of it. Flashy bloomsdahlias, giant chrysanthemums, and ruffled peonies. He cradled their heads in his huge hands. He cooed to them like a lover. Their enemies were his enemies. He picked off Japanese beetles with his bare fingers and drowned them in a can of kerosene. He called them Trumans.

My Uncle Yusuf loved me. One day, when it was just the two of us in his car, he asked the standard question. What do you want to be when you grow up? To be funny, I said, President. He said, Why not? A window in my mind flew open. I began to think things Id never thought before.

To American diplomats who urged Truman to hold off on recognizing Israel, he cited the wishes of American Jews: I am sorry, gentlemen, but I have to answer to hundreds of thousands who are anxious for the success of Zionism: I do not have hundreds of thousands of Arabs among my constituents.

On a Christmas show, back in the fifties, Perry Como croons carols on TV but also works in Jewish folk songs. My father, passing through the living room, overhears. Jews! he explodes. Do they control everything? I go into my bedroom and slam the door. Only years after he died did I begin to understand what it felt like for my father to be an Arab in the United States, reminded in every editorial, on every channel, that on matters that mattered, he could have no political voice.

Good that he didnt live to see 67 and Israels six-day blitzkrieg against Syria and Egypt, when newsmen and even comics on American TV gloated openly at Israels victory, when Arabs were mocked pitilessly.

The early seventies. Palestinians are hijacking airliners and planting bombs. After one horrific attack, Im on a bus, riding through a Boston neighborhood where Syrians and Lebanese have lived for decades. An old man climbs on. He is drunk and disheveled. Oh, Arabs, he cries out in Arabic, swaying from one overhead strap to another. His tears spill. Oh, brothers, what have you done! The driver, who has understood nothing, mutters an ethnic epithet and puts him off the bus.