About the Author

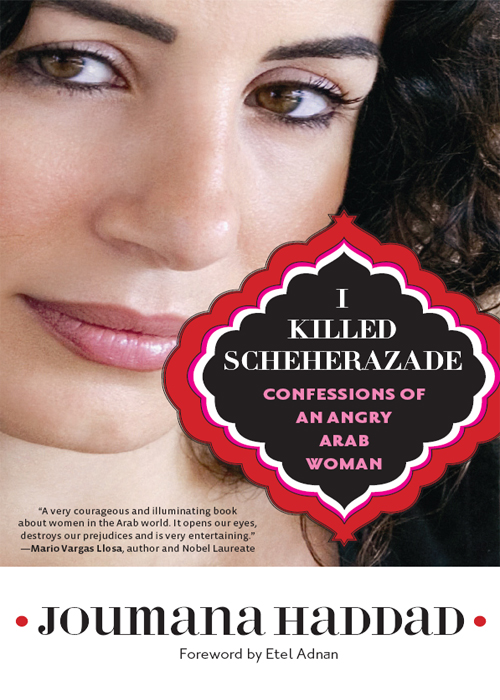

An award-winning poet and journalist, Joumana Haddad is also the cultural editor for an Arab newspaper, a magazine publisher, and a translator. In 2008 she launched the Arab worlds first erotic cultural magazine, JASAD (Body), which made international headlines and caused her to be dubbed the Carrie Bradshaw of Beirut. She lives in Lebanon.

Poet, novelist, and visual artist Etel Adnan was born in Beirut. She is the author of the classic Middle Eastern novel Sitt Marie Rose and divides her time among the United States, France, and Lebanon.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Haddad, Jumanah Sallum

I killed Scheherazade : confessions of an angry Arab woman / Joumana Haddad ; foreword by Etel Adnan.

p. cm.

Originally published: London : Saqi Books, 2010.

ISBN 978-1-56976-840-2 (pbk.)

1. Haddad, Jumanah Sallum. 2. Women, ArabSocial conditions.

3. Arab countriesSocial conditions. I. Title.

HQ1784.H273 2011

305.488927dc23

2011022057

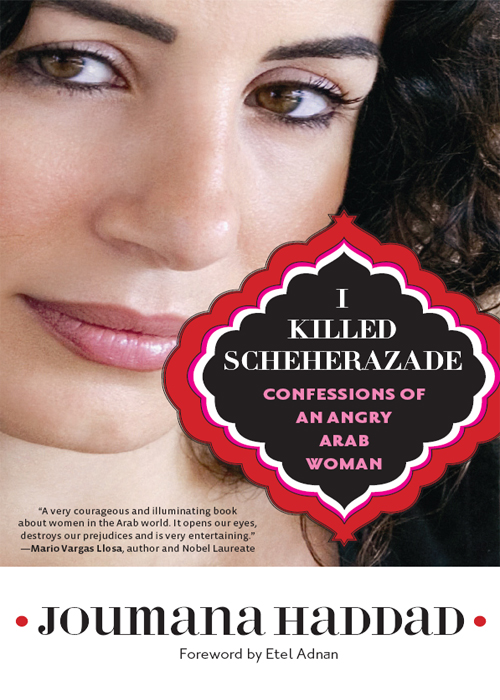

Cover design: Rebecca Lown

Cover photograph of the author: Hayat Karanouh

This edition published in 2011 by Lawrence Hill Books

First published in the United Kingdom by Saqi Books

Copyright 2010 by Joumana Haddad

All rights reserved

Foreword copyright 2010 by Etel Adnan

All rights reserved

Lawrence Hill Books is an imprint of

Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-56976-840-2

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

To my daughter,

The one I might/might never have,

Awaited, unexpected,

Wanted, feared,

Dreamed, held in arms,

Made of hope, made of flesh,

Real, unbelievable,

With a thousand names

Yet forever unnamed,

Born,

Unborn,

Loved in both her forests.

Contents

The Arab malaise is inextricably bound with the gaze of the Western Other a gaze that prevents everything, even escape. Suspicious and condescending by turns, the Others gaze constantly confronts you with your apparently insurmountable condition. You have to have been the bearer of a passport of a pariah state to know how categorical such a gaze can be. You have to have measured your anxieties against the Others certainties about you to understand the paralysis it can inflict.

Samir Kassir

Being Arab

Note to the Reader

The idea of this book started with a foreign journalist asking me, one rainy day in December 2008, how did an Arab woman like you reach the point of publishing a controversial erotic magazine like JASAD in Arabic? Were there any particular elements and precursors in my upbringing and background, she inquired, that paved the way for such an uncommon and polemic decision?

Most of us in the West are not familiar with the possibility of liberated Arab women like you existing, she added.

She had meant it as a compliment, of course, but I remember being provoked by her words and rather rude in my reply: I dont think I am that exceptional. There are many liberated Arab women like me. And if you are not aware that we exist, as you claim, then it is your problem not ours. Later that evening, I regretted my defensive reaction. Still, the journalists question remained stuck in my head, and I tried to understand better why she had asked it, and why it had irritated me to that extent. My attempt to understand soon became a small text; the small text developed into a long piece; the long piece then grew to become an expos; the expos combined with other texts I had produced around the same subject on various previous occasions; it all merged with some pertinent and revealing autobiographical notes I had written over the years; and the result was a book: this book.

Was it a good or a bad idea? Is it necessary or irrelevant? Too general? Too personal? Too scattered? Too self-absorbed? Its rather late for me to ask these, and similar, questions now. The only thing I know is that writing it felt inevitable. Inescapable, even. Much like a love story. And to me at least, that is enough of a justification.

However, having decided to publish it, I hope Ill find more justifications for it day after day, through the new life you, the readers, are going to give it.

Dear Jenny, please accept my very late apology for my needless rudeness towards you. I hope you can consider this modest testimony as a not-too-awkward attempt to say: Im sorry.

And, most importantly: Thank you.

Foreword

Etel Adnan

The latest news is that Scheherazade is dead, assassinated! Was it an act of passion or of reason? Probably both. Joumana Haddad has just killed the heroine from The Arabian Nights. And never has a crime been so joyous and moral.

The story of this killing is a stormy wind that clears the sky. Not the sky charged with monotheisms, but the sky that is a womans body, the personal body that belongs only to itself.

A historical myth had to be killed so the body, and therefore also the mind, could be liberated, and this experience had to be written so it could be better affirmed.

So, before listening to noise, we must listen to silence. Before sonorous words, there is the first word, the existence of the body, and Haddad proposes, not that we lose ourselves in its glorification, but that we listen to it.

I like this narrative-cum-analysis that resonates like jazz or rap music. And yet it is an indictment of impeccable logic punctuated by anger, by more than anger, by the ecstatic mystical search for absolute liberation, which would be possible only through the liberation of this objectsubject that is this body with which life begins and ends.

But from birth the body is mired in a social context, and it is thus that the constraints begin and lead us even into slavery.

Haddad rejects mild measures. Coming from a country where there has been much killing (and for nothing), she employs equally intense violence, but of a different nature. She strikes out against all taboos and her crime becomes a birth, an act of life.

She speaks of the Arab woman, of what is familiar to her, but what she says concerns all women throughout history, especially those of the Mediterranean region, where they are told with sacred authority that they are a sub-product of Creation, God having created Adam whereas Eve merely emerged from his rib. But Haddad brings the good news that woman comes only from herself, and that she must make herself, must create herself just like man. She must become the new Scheherazade, writing her tales to participate in the creation of the world through literature.

She brings the crucial questions of identity and of taking root back, not to the social me, which is more narcissistic than we think, but to the freedom she discovered as a child, and which is the shifting place of perpetual departure.

All of this is put into question with a wild joy and a surplus of intelligence that carry us along, in a text that in the end is a barbaric poem.

It takes genius to attain such radical freedom.

To Start With

On camels, belly dancing, schizophrenia and other pseudo-disasters

Dear Westerner,

Allow me to warn you right from the start: I am not known for making lives any easier. So if you are looking here for truths you think you already know, and for proofs you believe you already have; if you are longing to be comforted in your Orientalist views, or reassured in your anti-Arab prejudices; if you are expecting to hear the never-ending lullaby of the clash of civilisations, youd better not go any further. For in this book, I will try to do everything that I can to disappoint you. I will attempt to disillusion you, disenchant you, and deprive you of your chimeras and ready-to-wear opinions. How? Well, simply by telling you that:

Next page