The World of My Youth

IN TRYING to recount events that have influenced my life, it is humiliating to find that I remember very little of my childhood. Watching my great-grandchild Serena Russell at play, so sure of herself, even at the age of three, I wonder if, when she reaches my age, she also will have forgotten events that now appear important to her. That we are both in America she the child of my granddaughter Sarah Spencer-Churchill, who married an American, and I the wife of a Frenchman is due to World War II, and to events little anticipated at the turn of the century when I left my native land.

Memories of myself at Serenas age recall a picture painted by Carolus Duran of a little girl against a tall red curtain. She is wearing a red velvet dress with a square dcollet outlined with Venetian lace. A cloud of dark hair surrounds a small oval face, out of which enormous dark eyes (much bigger than they were) look out from under arched brows. A pert little nose and dimples accentuate the mischievous smile. There is something vital and disturbing in that small figure tightly grasping a bunch of roses in each fist. You were un vrai petit diable , and only kept still when I played the organ in my studio! Carolus Duran exclaimed, when again he painted me, this time at seventeen. The second portrait was a very different affair from the first, for the red curtain which had become his traditional background was at my mothers request replaced by a classic landscape in the English eighteenth-century style, and I am seen a tall figure in white descending a flight of steps. For my mother, having decided, in the fashion not uncommon at the time, to marry me either to the man who did become my husband or to his cousin generously allowing me the choice of alternatives wished my portrait to bear comparison with those of preceding duchesses who had been painted by Gainsborough, Reynolds, Romney and Lawrence. In that proud and lovely line I still stand over the mantelpiece of one of the state-rooms at Blenheim Palace, with a slightly disdainful and remote look as if very far away in thought.

It is well that my Aunt Florence Twombly, now ninety-eight, could remember not only the street but also the number of the house where I was born, for my birth had never been officially recorded. This information was required when I took back my American citizenship after the French armistice in World War II. It was in one of those ugly brownstone houses somewhere in the forties, which was then the fashionable district of New York, that I first saw the light of day.

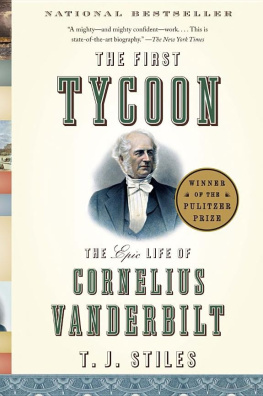

My fathers family was Dutch and had its origin in the Bilt that northern point of Holland whence comes our name. It was about the year 1650 that the first member of the family came to the New Netherlands, and succeeding generations lived in the vicinity of New Amsterdam, as New York City was then called. In the first part of the nineteenth century my great-grandfather Cornelius Vanderbilt founded the family fortune, moved from New Dorp, Staten Island, to New York and changed the spelling of our name from van der Bilt to its American version. In later years I met a Professor van der Bilt who taught at a Dutch University. He told me that there was only one family bearing our name in Holland, and in looking through his family archives he had become convinced that the Dutch and American branches had descended from a common ancestor. In the Patriciat , a book that is the Dutch equivalent of the British Landed Gentry , the Professor pointed out our coat of arms, the three acorns, and the names Gertrude, Cornelius and William, which repeatedly figure in our family Bible.

My grandfather, William H. Vanderbilt, had, considering his numerous philanthropic gifts, an unmerited reputation for indifference to the welfare of others. It was, as is often the case, founded on a remark shorn of its context. This is the version of the public be damned story that was given me by a friend of the family. Mr.Vanderbilt was on a business trip and, after a long and arduous day, had gone to his private car for a rest. A swarm of reporters arrived asking to come on board for an interview. Mr. Vanderbilt sent word he was tired and did not wish to give an interview, but would receive one representative of the Press for a few minutes. A young man arrived saying, Mr. Vanderbilt, your public demands an interview! This made Mr. Vanderbilt laugh, and he answered, Oh, my public be damned. In due course the young man left and next morning his article appeared in the paper with a large headline reading, Vanderbilt says, The Public be damned. That he was not so black as painted I have from a cousin to whom my grandmother after her husbands death said, Your grandfather never said an unkind word to me during all the years we were married.

In The House of Vanderbilt by Frank Crowninshield, I find a reference to my grandmother in which he says, She was an amazing woman who brought up her children to become people of the greatest cultivation and taste. She had been born Maria Louisa Kissam, the daughter of a clergyman of the Dutch Reformed Church. The Kissams were an old and distinguished family, Mrs. Vanderbilts father having descended from the Benjamin Kissam who, in 1786, married Cornelia Roosevelt, the daughter of the patriarchal Isaac, and the Presidents great-great-grandfather. Of my grandmothers eight children my father, W. K., as he was known to his friends, was the second son. I remember my grandmother very well, and our visits to her in the big house on Fifth Avenue directly opposite St. Patricks Cathedral where she lived. She was a lovely old lady, gracious and sweet as old ladies should be. All her grandchildren we were, I think, twenty-six loved her. After my grandfathers death in 1885 she lived alone with her youngest son, George. Uncle George was quite different from my other uncles and aunts. With his dark hair and eyes, he might have been a Spaniard. He had a narrow sensitive face, and artistic and literary tastes. After my grandmothers death in 1896 he createdBiltmore, a great estate in North Carolina where he built model houses and fostered village industries.

My fathers eldest brother Uncle Corneil, as we called him, was a stern and serious person, or so we thought. He was not gay like my father and Uncle Fred. Of my four aunts I loved my Aunt Emily Sloane best, for, like my father, she was of a joyous nature and had the look of happy expectancy one sees on the faces of those who love life. She and my Aunt Florence were always perfectly dressed, and, with their slight figures and quiet distinction, reminded me of Jane Austens charmingly prim ladies. Some time before her death I went to see Aunt Emily. She was sitting at a window overlooking Central Park. It struck me that her days must have been very long, now that she was widowed and that the bridge game she loved was no longer possible because of her failing memory. But when I sympathised with her, she folded her hands and softly smiling answered I have such lovely thoughts to keep me company, and when I crept away, fearing to disturb them, I heard her murmuring, as if conversing with ghosts of the past. She lived to be over ninety. At her memorial service the Rector of St. Bartholomews in New York paid a well-deserved tribute to her lovely character and generous charity.

My maternal grandfather, Murray Forbes Smith, was descended from the Stirlings, and both my mothers given names Alva Erskine are Stirling names. The Scotch tradition of large families is borne out in two volumes on the Stirlings in America. This prolific family overflowed from Virginia into the more southern states and produced several governors and people of importance. All this accentuated in my mother a pride in her Southern birth and a certain disdain for the mercenary spirit of the North. Her father, who owned plantations near Mobile, was ruined by the liberation of the slaves and, after the Civil War, moved to Paris. There my mothers eldest sister made her dbut at one of the last balls given at the Tuileries by Napoleon III. My mother and I used to attribute our love for France to a Huguenot ancestor who escaped to America after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Indeed we were happier in France than in any other country, and, following the example of an aunt and a great-aunt, we both returned to live there.