Cornelius K. Garrison

George W. Vanderbilt

William H. Vanderbilt

INSERT FOLLOWING PAGE 531

USS Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt

Sighting the Alabama

Capture of the Ariel

Harlem Railroad Station, Twenty-sixth Street and Fourth Avenue

Commodore Vanderbilt locomotive

Hudson River Railroad Station, Chambers Street

Horace F. Clark

Augustus Schell

The Albany Bridge

Henry Keep

Erastus Corning

Jay Gould

James Fisk Jr.

Thomas A. Scott

St. John's Park Freight Depot

The Vanderbilt statue

Stock watering (cartoon)

Racing Fisk (cartoon)

Grand Central Depot under construction

Grand Central Depot

Grand Central Depot car house, exterior view

Grand Central Depot car house, interior view

Fast train to Chicago

New York Central & Hudson River Railroad

Fast trotters on Harlem Lane

Mountain Boy

Congress Hall veranda, Saratoga Springs

Cornelius Vanderbilt

Tennessee Claflin

Victoria Woodhull

Horace Greeley

Frank Crawford Vanderbilt

Ethelinda Vanderbilt Allen

Sophia Vanderbilt Torrance

Mary Vanderbilt La Bau

Going to the Opera

The run on the Union Trust

Vanderbilt at rest

Death of Cornelius Vanderbilt

Funeral of Cornelius Vanderbilt

Burial of Cornelius Vanderbilt

Dr. Jared Linsly at the will trial

New York, 1880

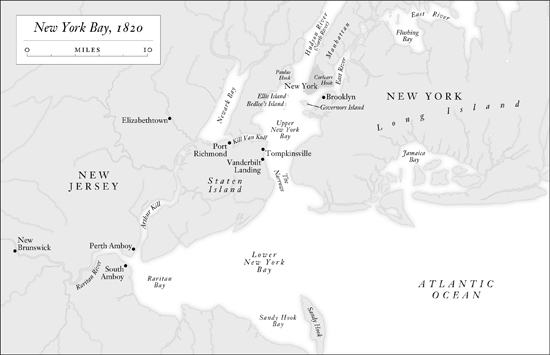

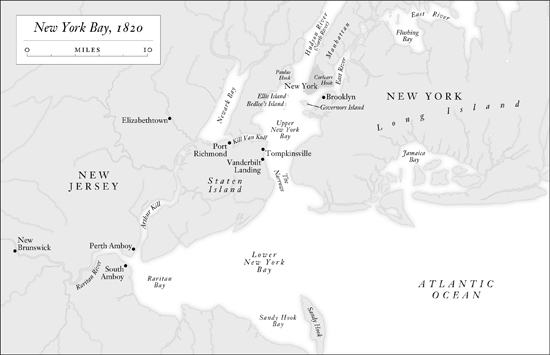

Maps

Chapter One

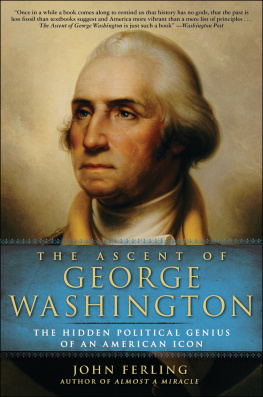

THE ISLANDER

T hey came to learn his secrets. Well before the appointed hour of two o'clock in the afternoon on November 12, 1877, hundreds of spectators pushed into a courtroom in lower Manhattan. They included friends and relatives of the contestants, of course, as well as leading lawyers who wished to observe the forensic skills of the famous attorneys who would try the case. But most of the teeming mass of men and womenmany fashionably dressed, crowding in until they were packed against the back wallwanted to hear the details of the life of the richest man the United States had ever seen. The trial over the will of Cornelius Vanderbilt, the famous, notorious Commodore, was about to begin.

Shortly before the hour, the crowd parted to allow in William H. Vanderbilt, the Commodore's eldest son, and his lawyers, led by Henry L. Clinton. William, glancing carelessly and indifferently around the room, removed his overcoat and comfortably settled himself in his chair, the New York Times reported; meanwhile his lawyers shook hands with the opposing team, led by Scott Lord, who represented William's sister Mary Vanderbilt La Bau. At exactly two o'clock, the judgecalled the Surrogate in this Surrogate Courtstrode briskly in from his chambers through a side door, stepped up to the dais, and took his seat. Are you ready, gentlemen? he asked. Lord and Clinton each declared that they were, and the Surrogate ordered, Proceed, gentlemen.

Everyone who listened as Lord stood to make his opening argument knew just how great the stakes were. THE HOUSE OF VANDERBILT , the Times headlined its story the next morning. A RAILROAD PRINCE'S FORTUNE. THE HEIRS CONTESTING THE WILL. A BATTLE OVER $100,000,000. The only item in all that screaming type that would have surprised readers was the Times's demotion of Vanderbilt to prince, since the press usually dubbed him the railroad king. His fortune towered over the American economy to a degree difficult to imagine, even at the time. If he had been able to sell all his assets at full market value at the moment of his death, in January of that year, he would have taken one out of every twenty dollars in circulation, including cash and demand deposits.

Most of those in that courtroom had lived their entire lives in Vanderbilt's shadow. By the time he had turned fifty he had dominated railroad and steamboat transportation between New York and New England (thus earning the nickname Commodore). In the 1850s, he had launched a transatlantic steamship line and pioneered a transit route to California across Nicaragua. In the 1860s, he had systematically seized control of the railroads that connected Manhattan with the rest of the world, building the mighty New York Central Railroad system between New York and Chicago. Probably every person in that chamber had passed through Grand Central, the depot on Forty-second Street that Vanderbilt had constructed; had seen the enormous St. John's Park freight terminal that he had built, featuring a huge bronze statue of himself; had crossed the bridges over the tracks that he had sunk along Fourth Avenue (a step that would allow it to later blossom into Park Avenue); or had taken one of the ferries, steamboats, or steamships that he had controlled over the course of his lifetime. He had stamped the city with his marka mark that would last well into the twenty-first centuryand so had stamped the country. Virtually every American had paid tribute to his treasury.

More fascinating than the fortune was the man behind it. Lord began his attack by admitting that it seemed hazardous to say that a man who accumulated $100,000,000 and was famous for his strength of will had not the power to dispose of his fortune. His strength of will was famous indeed. Vanderbilt had first amassed wealth as a competitor in the steamboat business, cutting fares against established lines until he forced his rivals to pay him to go away. The practice led the New York Times, a quarter of a century before his death, to introduce a new metaphor into the American vernacular by comparing him to the medieval robber barons who took a toll from all passing traffic on the Rhine. His adventure in Nicaragua had been, in part, a matter of personal buccaneering, as he explored the passage through the rain forest, piloted a riverboat through the rapids of the San Juan River, and decisively intervened in a war against an international criminal who had seized control of the country. His early life was filled with fistfights, high-speed steamboat duels, and engine explosions; his latter days were marked by daredevil harness races and high-stakes confrontations.