Table of Contents

Praise forCommodore

A valuable update to our knowledge of a man who had a huge impact on the development of American life in the 19th century.

Providence Journal

Renehan succeeds in his quest of bringing the colorful, controversial character of Cornelius Vanderbilt back to life.

The Scotsman

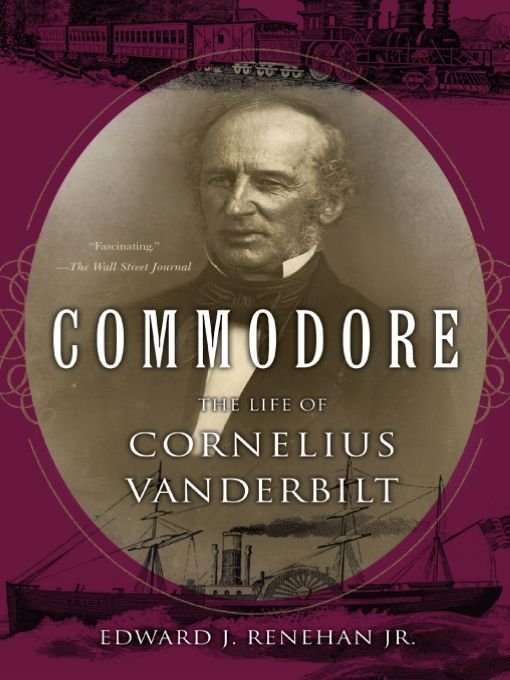

Reveals hidden secrets from the life of Vanderbilt, the progenitor of modern American business, who was known as the Commodore. Using several previously unreleased archives, including those of Vanderbilts personal physician, this biography sheds new light on the many startling aspects of his personal and business life.

Library Journal

Renehan absorbingly traces this fascinating endowers start from the gate and his race to the finish line.

Chronogram

Commodore explores the tycoons dark family life, erratic later years, and his terminal bout with syphilis. The authors attention to detail and exhaustive research paints a unique picture of a man who was hated, loved, admired, and reviled.

Hudson Valley Magazine

Exhaustively researched, Commodore spans George Washingtons presidency, the War of 1812, the building of the Erie Canal, the Civil War and construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. Such momentous occasions serve as backdrop for the life story of this descendant of Dutch immigrants, who made his first wealth in ferry routes and shipping cargo in and around New York harbor.

The Tennessean

Your favorite bookworm will welcome a copy of Commodore. The Hudson River was important to the Commodore in all phases of his lifesailing vessels, steamboats, railroads. He was an original incorporator of the track at Saratoga and his grandson, Frederick, owned a massive estate at Hyde Park.

The Independent

Edward J. Renehan Jr.s Commodore, the first re-evaluation of Vanderbilts life since 1942, focuses deeply on the ambiguity of the entrepreneurs professional self and the untold secrets of his personal life, including his many affairs and a chronic case of syphilis that led to dementia.

The Vanderbilt Hustler

Renehans writing proves colorful, insightful and efficient.

Publishers Weekly

In this remarkable and engrossing work, leading historian Edward J. Renehan Jr. brings Commodore Vanderbilt to lifeshedding new light on one of the architects of modern America. In the first major reexamination of Vanderbilt since 1942, Renehan masterfully utilizes major new sources, uncovering extraordinary details in his portrait of a life at once monumental and poignantly human.

James Strock, author of Theodore Roosevelt on Leadership

Also byEDWARD J. RENEHAN JR .

Dark Genius of Wall Street:

The Misunderstood Life of Jay Gould, King of the Robber Barons

The Kennedys at War

The Lions Pride

The Secret Six

John Burroughs: An American Naturalist

This book is warmly dedicated to

Marie Kutch, Nikki Natale and John Staudt,

who know why

PREFACE

AT FORTY-SECOND STREET AND PARK AVENUE IN NEW YORK City, busy travelers rush in and out the large doors of an architectural gem: Grand Central Station, built on the site of Cornelius Vanderbilts original Grand Central Depot of 1871. Long known as the gateway to the nation, 1913s Beaux-Arts masterpiececonstructed by Corneliuss great-grandson William K. Vanderbilt IIis today dominated by commuters from New Yorks Westchester County: riders of MetroNorth, a remnant of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilts old New York Central. High above, at the precipice of the stations front, a massive Tiffany clock sits in the middle of a large figurative sculpture by Jules Felix Couton. Mercury, Hercules, and Minervathe Roman gods of travel, strength, and wisdom, whom Couton assembled to sum up his assigned theme of Transportationdrape themselves around the timepiece. By day or by night (but especially at night, when floodlights work their magic) pedestrians strolling north along lower Park Avenue cannot help but be impressed by the enormous lounging divinities.

Several hundred feet beneath the seminude figures, close to street level, stands a barely noticeable (and thoroughly clothed) statue of the Commodore: builder of the original Second Empire-style terminal on this site. Although heroically proportioned, the bronze Vanderbilt nevertheless seems diminutive when compared to Coutons Transportation and the massive backdrop of the palace-like station. Barely head-and-shoulders above the rushing taxis and street grime, the bald financier, dressed in a fur-lined coat, seems somehow aware of his reduced status. He glowers grimly and stares south toward the downtown district that was once, in his day, the heart of New York. The mute Vanderbilts left hand juts outward, the index finger extended. Its as though he has some stern injunction hed issue, if he could, to the distracted motorists rushing over and through Pershing Square.

The statue is one of which Vanderbilt, who died in 1877 at the age of eighty-three, knew and approved. In Vanderbilts time, the same piece began life outside yet another New York Central depot. First revealed to public view in 1871, Ernst Plassmanns version of Cornelius stood at a lofty height above the Hudson River Rail Road Freight House, known more popularly as the St. Johns Park Freight House, on Hudson Street. There it formed the apex of an ambitious rooftop pediment more than a hundred feet long and thirty-one feet wide. On each side of the statue, bas-relief figures documented Vanderbilts various triumphs on land and sea. To the Commodores left were represented icons of his early days when hed first earned that honorific: schooners and steamships with which hed been associated on the Hudson River, Long Island Sound, and the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. To his right, meanwhile, lingered symbols of his later conquests: trains, tunnels, bridges. And at his feet lay a cacophony of engines, cables, anchors, and wheels.

Plassmanns reputation as a sculptor has not endured. Works such as that described above, reviled in its own time, are the reason why. Horace Greeley (a fan of the Commodores who joined with Vanderbilt in the unpopular task of posting a bail bond for Jefferson Davis after the end of the Civil War) used his column in the New York Tribune to comment on the bronze, leaving other aspects of the pediment undescribed. As a likeness, wrote Greeley, the statue signally fails to do justice to that physiognomy, one of the finest in America, which has never yet been rendered worthily by any photograph, bronze, or picture that we have seen. The Manhattan attorney George Templeton Strong (a trustee of Columbia University and president of the New York Philharmonic Society) criticized the entire installation within the privacy of his diary: Have inspected the grand $800,000 Vanderbilt bronze. Its a mixellaneous biling [sic] of cog-wheels, steamships, primeval forests, anchors, locomotives, periaugers (pettyaugers we called them when I was a boy), R.R. trains, wild ducks (or possibly seagulls) & squatter shanties, with a colossal Cornelius Vanderbilt looming up in the midst of the chaos, & beaming benignantly down on Hudson Street, like a Pater Patriaedraped in a dressing gown or overcoat, the folds whereof are most wooden. As a work of art, it is bestial.