Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

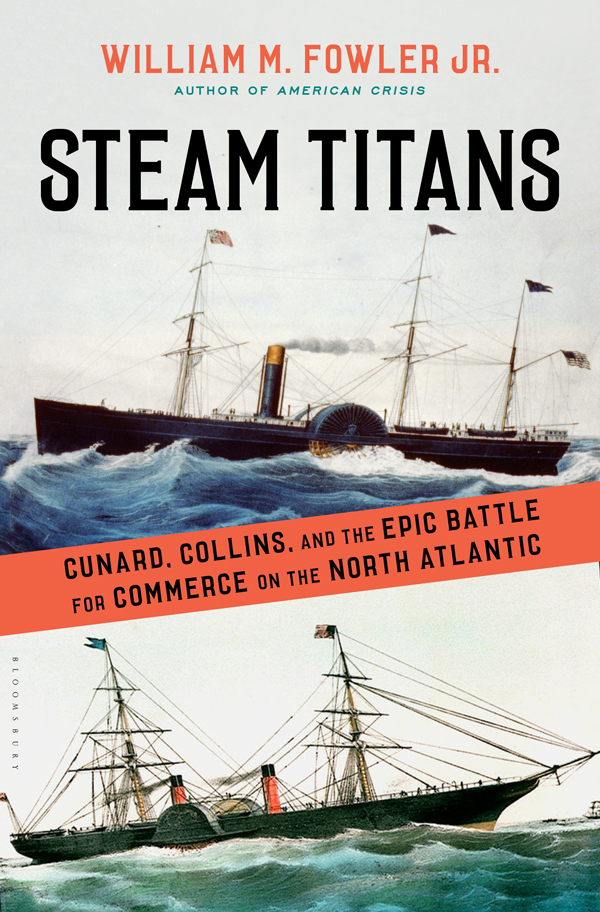

STEAM TITANS

To: Olivia

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

William Ellery: A Rhode Island Politico and Lord of Admiralty

Rebels Under Sail: The American Navy in the Revolution

The American Revolution: Changing Perspectives (coeditor)

The Baron of Beacon Hill: A Biography of John Hancock

Jack Tars and Commodores: The American Navy, 17831815

Under Two Flags: The Navy in the Civil War

Silas Talbot: Captain of Old Ironsides

Samuel Adams: Radical Puritan

America and the Sea: A Maritime History (coauthor)

Empires at War: The French and Indian War and the Struggle for North America, 17541763

American Crisis: George Washington and the Dangerous Two Years After Yorktown, 17811783

CONTENTS

In 1492, Christopher Columbus crossed the Atlantic in thirty-five days; three centuries later, passage from Europe to America took just as long. During the early nineteenth century, Atlantic voyagers still sailed aboard wooden vessels powered by the natural energies of man and nature, muscle and wind. Between 1815 and the American Civil War, however, there was a sea change in oceanic transportation, delivered by the greatest

Ashore, steam-powered factories consumed vast quantities of raw materials, turning them into a stunning array of goods. Mass production, in lowering prices, spurred mass consumption. Decreasing the costs and increasing the momentum of transportation, steam at sea, linked in turn to rails on land, overwhelmed the traditional world of sail. In a single year, for example, one steamship could easily complete more than a dozen round-trips between New York and Liverpool, whereas masters of sailing vessels were fortunate if they managed three. Between 1820 and 1860, cargo clearing the port of New York increased more than fifteen-fold. American raw materials and foodstuffs flowed into England and Europe, satisfying the demands of industrialization and feeding millions of workers, while westbound vessels carried manufactured goods and immigrants to an emerging American empire. Because it allowed for a rapid and reliable exchange of information, steam passage reduced uncertainty about price and supply, which created a stable economic environment. Thanks to the steamship, the Atlantic world grew interdependent and prosperous.

Two ports, Liverpool and New York, the Atlantic antipodes, gained dominance. Each was blessed by geography, but only when their citizens brought entrepreneurial talent to natures gifts did the ports thrive. Steamships demanded new servicescoal, repair facilities, larger docks, sizeable warehouses, and links (rail, canal, rivers, coastwise) to distant markets. Guided by skilled management and funded with deep capital reserves, the ports developed a level of efficiency unmatched in the Atlantic world.

Liverpool entered the fray with a distinct advantage. Given its ready access to the English midlandsheartland of the Industrial RevolutionLiverpool enjoyed a well-ordered port system. Her merchants and bankers had extensive experience in Atlantic shipping. Moreover, they benefited from the support of an imperial government determined to strengthen the sinews of empire, and they had long drawn upon the rich resources of Londons private-money market as well as of the Bank of England.

In 1838, the British steamship Sirius made its maiden voyage across the Atlantic from Liverpool to New York. That same year, a rebellion in Upper Canada stirred rumors that America had instigated the uprising and might be planning to invade. Appealing to the Colonial Office, Canadian officials argued that security depended upon establishing a line of rapid communication by steam. The ministry agreed; it invited tenders, with the enticement of a generous subsidy for anyone who would guarantee regular steamship service between Halifax, Nova Scotia, and Liverpool. Samuel Cunard, a Canadian familiar with both ports, submitted the successful bid. He christened his enterprise the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company. Everyone called it the Cunard Line.

Americans were flabbergasted. For years, Liverpudlian shipowners had lamented the loss of business to the Yankee sailing packets, but the rules of the game were shifting and the United States was unprepared. American shipowners, unlike their English counterparts, suffered from a shortage of capital, aggravated by a parsimonious national government unwilling to proffer aid. The demise of the Bank of the United States (1836) threw American markets into disarray, as capital was dispersed among hundreds of loosely regulated state banks. Credit was limited, and compared to London, interest rates were high. The costs of building and operating steamships far exceeded the capacity of traditional partnerships, while the mounting complexities of international finance baffled the clerks tallying accounts in waterfront counting houses.

In 1825 James Brown, one of four sons of Alexander Brown, a successful Baltimore merchant and banker, arrived in New York to set up a branch office. Thanks to another brother, William, who had moved to Liverpool, the Brown Brothers forged a strong transatlantic network. Within a few years, they were Americas most influential players in currency exchange and international banking. When Edward Knight Collins, a Cape Codder transplanted to New York, stepped forward to challenge Cunards domination of transatlantic steam travel, the Browns were behind him. An indefatigable promoter and shipowner, Collins also successfully lobbied Congress. Like the British, the U.S. government extracted a political and military quid pro quo for its support: Collinss vessels must be readily convertible to warships. His commitments in place and optimism his watchword, Collins built a series of magnificent steamships. The first, the Atlantic , steamed out of New York Harbor, bound for Liverpool, in April 1850.

For nearly a decade, in a quintessential Anglo-American rivalry, Cunard and Collins mounted a colorful, pitched battle to wrest control of the globes most lucrative trade route: the North Atlantic. Through their lives and through the ports they represented, New York and Liverpool, these two fierce competitors sent to sea the fastest, biggest, and most elegant ships in the world, hoping that each in turn might earn the distinction of being known as the only way to cross. In their clash for supremacy, Collins and Cunard employed every weapon available to themtechnology, money, secret deals, bribery, government influencewhile at the same time coping with the inevitable, sometimes crushing, perils of the sea. In the midst of this spectacleand in no small part because of itNew York rose to take her place among the greatest ports and cities of the world.

As the icons of their respective countrys merchant marines, Collins and Cunard embodied and reflected their nations goals and commitments. For Great Britain, an island state in possession of a vast empire, the sea was a primary and indispensable conduit for transferring knowledge and values as well as goods or, in times of war, armies and supplies. For the United States, with its immense hinterland, much of it still to be claimed, settled, and rendered productive, the merchant marine was less attractive to capitalists and legislators than were railroads and canals. Great Britain kept a steady hand on the throttle, while America was always peering over the horizon to the next best opportunity. Neither fortitude nor enterprise prevailed in the long run. By the early twenty-first century, among the worlds seafaring nations, the United States ranked a lowly 26th in the number of her merchant vessels, while her old rival Great Britain did little better at 22nd.