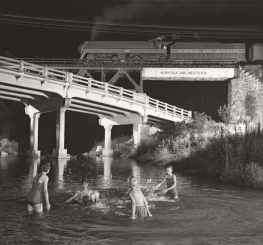

CLASS Y-6B IN THE WASH BAY AT BLUEFIELD. BLUEFIELD, WEST VIRGINIA, JULY 27, 1955, NW 343

O . WINSTON LINK

LIFE ALONG THE LINE

A PHOTOGRAPHIC PORTRAIT OF AMERICAS LAST GREAT STEAM RAILROAD

TONY REEVY

FOREWORD BY

SCOTT LOTHES

AFTERWORD BY

CONWAY LINK

ABRAMS, NEW YORK

ELECTRICIAN J. W. DALHOUSE CLEANS A HEADLIGHT. SHAFFERS CROSSING ROUNDHOUSE, ROANOKE, VIRGINIA, MARCH 19, 1955, NW 8

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

BY SCOTT LOTHES

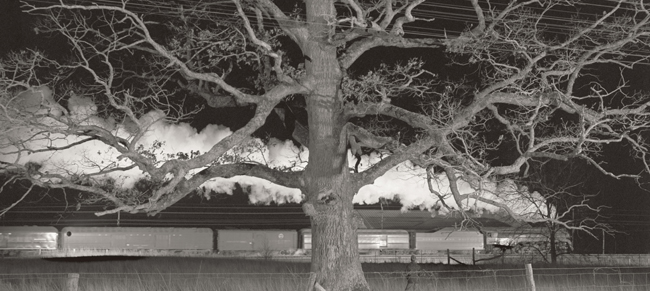

I n Appalachiawhere O. Winston Link photographed the Norfolk and Western Railway and also where I grew upthere is a long tradition of storytelling. On remote mountain farms in areas that lacked schools and even the means for writing, stories were often the only way of preserving heritage, just as people everywhere had done for millennia. The art of those stories was in the form of the telling and the retelling, which occurred almost exclusively at night. Part of the reason was practicalitythere was no time for stories during the hard work of the day. But practicality was only part of it. The night shut out all other distractions, and in its void those stories could grow, and the listeners could contribute their own contextual imagery.

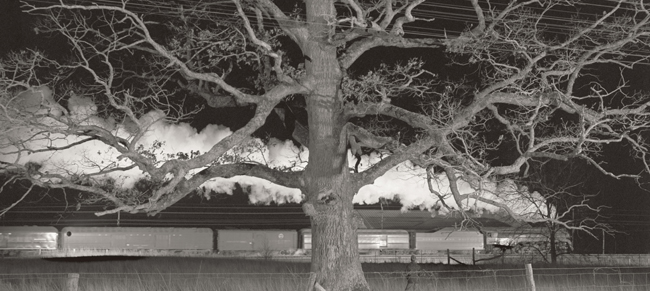

It is fitting that Winston Link applied this quality of the night to his momentous photography effort about the N&W. His engineering education and commercial photography experience provided an ideal background for both recognizing the potential for his night photos and executing them with theatrical brio. Artificial lighting allowed Link to include exactlyand onlywhat he wanted to include.

His critics, and even some of his admirers, find an argument here. By excluding the distractions, they say, he left out too much. Many of his photographs depict a hyperreality that is largely free of the grit we know to have existed in the small-town Appalachia of the late 1950s. But such a straight-up view was never Links goal, and even in the art photography community such an approach would not become widely practiced until the New Topographics movement of the 1970s.

More than fifty years after Link made his last pictures on the N&W, his name has become synonymous with night railroad photography. Digital imaging, with its instant feedback and high sensitivities (offering sixteen times more light-gathering capability than the film Link used), has led to an explosion of amateur night photography. Many of todays practicing photographers, myself and uncounted other twenty- and thirty-somethings included, turn to Links work when seeking ideas or inspiration for nocturnal views. His previous two books were among the first railroad photography books I owned, and they continue to occupy places on my shelves that are within easy reach. Those of us in the railroad photography community frequently and invariably draw comparisons to Link. It matters not that railroad and camera technology have changed drastically, that diesel locomotion replaced steam, and that many of todays young practitioners have never loaded film into a camera or picked up a flashbulb. If a recent railroad night photo is compelling, someone on an Internet discussion board will give it the Link stamp of approval. The cover story of the September 2008 issue of Trains, the nations foremost railroad magazine, featured one of these current night photographers. The subtitle asked, Is Gary Knapp the next O. Winston Link?

Links photographic legacy extends beyond American soil. One of his first major exhibitions occurred in London, and Germany has produced two of his greatest disciples, Axel Zwingenberger and Olaf Haensch. Steam lasted longer in Germany than it did in the United States, especially in the former East Germany, where steam continued in regular service on some lines into the 1990s. Many steam locomotives still operate on tourist railroads and special trains for enthusiasts. Zwingenberger and Haensch drew directly on inspiration from Links work and embarked upon substantial, personally motivated night photography endeavors about Germanys steam trains. Neither had to wait decades for fame as Link did. Both published well-received books almost immediately that appeal to train-lovers and the general public alike: Zwingenbergers Vom Zauber der Zge (The Magic of Trains) in 2000, and Haenschs NachtZge (Night Trains) in 2010.

Although he is most acclaimed for his night work, Link also made a substantial number of daytime photographs on the N&W, with ) evoke the creativity of Richard Steinheimer, Jim Shaughnessy, and Philip R. Hastings.

But it was in the void of the night that Link created his most significant works, none more renowned than 1956s Hotshot Eastbound (NW 1103; see ). When the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City mounted an international loan show of railroad art in 2008, The Railway: Art in the Age of Steam, curator Ian Kennedy chose Link to carry the banner for all American railroad photographers of the late steam era. Kennedy wrote that Links photos stand out among the vast and often distinguished corpus of post[World War II] railway photography. While the show included several of Links daytime photos, his most prominent was Hotshot Eastbound. The drive-in movie photos pop culture fame includes a series in the comic strip Gasoline Alley (where Link received the pseudonym O. Winken Blink) and a re-creation in a 1998 episode of The Simpsons, Dumbbell Indemnity.

Even in the 1950s, Link was not alone as a night photographer of steam railroads. Steinheimer, Shaughnessy, Hastings, and others practiced night photography, experimenting with ambient light, open flash, and synchronized flashoccasionally with great success. The 2000 Starlight on the Rails exhibition at New Yorks Robert Mann Gallery presented some of their and their successors best night work. Today, technological advances in both lighting equipment and digital imaging have made night photography easier than ever, and twenty-first-century railroad photographers, including some still in their teens, produce results that are sometimes stunning. Yet for all the night railroad photography that has followed Links, his work remains the standard by which all of our efforts are judged.

Like Appalachias tradition of storytelling, Links photographs preserve and create memories. They have achieved international acclaim because they transcend geographic and generational boundaries, and even the locomotives themselves. For a century, the wailing whistle of a passing steam trainespecially that of a night expresswas the voice of progress, hopes and dreams, and escape, not only in America but also in much of the developed world. Link captured that voiceliterallyin his sound recordings (some of the most lyrical and artistic ever made of railroad subjects). But he also found a way to convey that aural phenomenon through pictures that seem to talk, telling stories in the night.

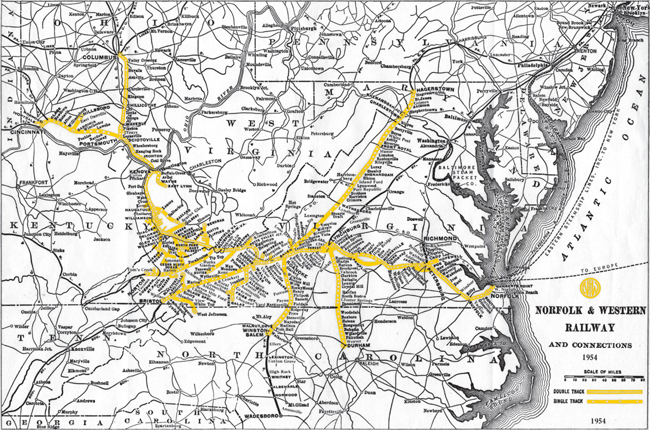

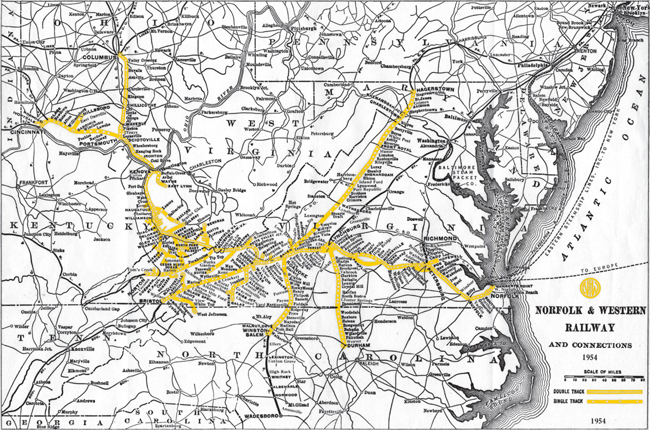

Links genius lay in looking at the region surrounding the Norfolk and Western Railway in Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina in the late 1950s and finding what it was about that time and place that he wanted to remember for himself and wanted others to know and think about. His photographs continue to resonatemore than fifty years after he made the last onebecause so many of us want to build the same memories and tease our imaginations with them. Our internal dialogues with his photographs, as with all art, occur inevitably and unbidden.

Next page