Lorenzsonn, Axel S.

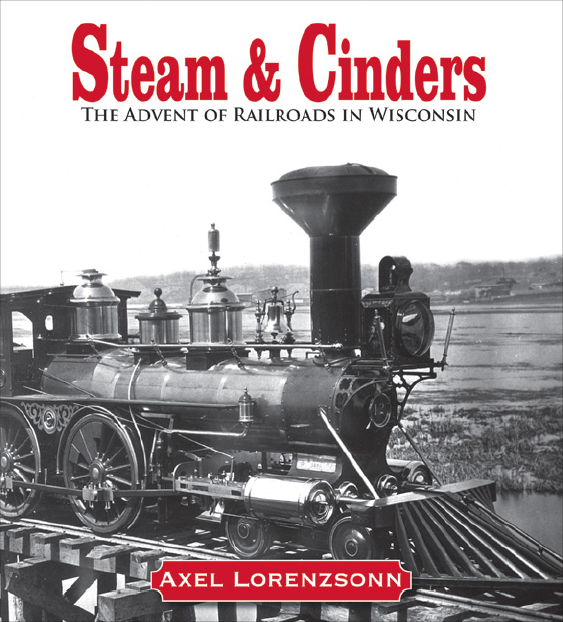

Steam and Cinders : the advent of railroads in Wisconsin, 1831-1861 / Axel S. Lorenzsonn.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87020-385-5 (hbk : alk. paper)

1. RailroadsWisconsinHistory19th century. 2. Milwaukee and Mississippi Railroad CompanyHistory. I. Title.

Acknowledgments

History and story are the same word differently written.

Moses M. Strong

We are more eager to have railroads than we are to get to heaven.

Anonymous Wisconsin pioneer

I have long loved history. My childhood summers were spent at the beach lying on a damp towel and reading books about Revolutionary War heroes, frontiersmen, and Native Americans. In college I was taken by Juliette McGill Kinzie's Wau-bun: The Early Day in the Northwest, her account of living in Wisconsin in the 1830s. And for the last ten years I have been collecting stories of Wisconsin's early railroads.

Why railroads? The train bug bit me a number of years ago while I was shopping for a toy train for my son. I then became curious about the origin of railroads in Madison, where I live. A trip to the Wisconsin Historical Society Library revealed to me that the first train to arrive in Madison came from Milwaukee on May 23, 1854. It had two locomotives, thirty-two cars, and one thousand passengers and was met at the depot by some two thousand Dane County residents, most of whom had never seen a train before. At the Madison Public Library in the 1858 city directory I found advertisements for railroads with fascinating names such as the Milwaukee and Mississippi, the La Crosse and Milwaukee, and the Chicago, St. Paul and Fond du Lac. I was hooked.

When I first began collecting early Wisconsin railroad stories, I found that they were few and scattered. Pictures and photographs are rare. There are several summaries of early railroad development in local Wisconsin histories, but no book exists on the topic. With the encouragement of family and friends, I decided to try to write such a book. The result is Steam & Cinders, the story of the first thirty years of railroads in Wisconsin.

I would like to thank the people who helped make this book possible, although I regret I cannot name them all. I thank my wife, Nandini, my daughter, Faye, and my son, Erik, for being supportive and for reviewing sections of the manuscript. Thanks to my parents, Edgar and Vila Lorenzsonn, for insisting that I was a railroad historian and giving me confidence. Thanks to my mother-in-law, Josephine Sarkar, for giving me a copy of Stephen Ambrose's Nothing Like It in the World, which became the model for this book. Thank you to Dr. Stephen Weiler for helping me keep my focus. Thank you to the Madison Public Library's Sue Koehler, a now-retired librarian who helped me find and use reference guides; to the staff at the Wisconsin Historical Society Archives for helping me locate maps and other materials; to the volunteers in the society's microfilm room for their assistance and good cheer; to freelance editor John Toren for reading the manuscript thoroughly and offering many valuable suggestions; and to Wisconsin Historical Society Press editors Kate Thompson and Sara Phillips for their editing, guidance, and support. Thanks to all of the folks at the local historical societies for digging for those elusive preCivil War railroad itemsI was touched by their attention and courtesy. And finally, a special thank you to former Wisconsin Historical Society Press editor J. Kent Calder for giving me encouragement, direction, and so much of his time.

PART ONE: BEGINNINGS

Chapter 1

A Proposal

1831

In 1831 the United States was forty-two years old; its lands stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Rocky Mountains, and Andrew Jackson was president. There were twenty-four states in the Union at the time, and all but Louisiana and Missouri lay east of the Mississippi river. Slavery was practiced in the twelve southern states and prohibited in the twelve northern states. The United States owned and administered the areas known as Florida Territory, Arkansas Territory, and Michigan Territory, from which future states were expected to emerge. The remaining areas of the United Statesthe lands west of Arkansas Territory, Missouri, and the upper Mississippi River, and extending to the Rocky Mountainswere Indian Territory. There, settlement by whites was prohibited. Both the United States and Britain claimed the Pacific Northwest, while Texas, the Southwest, and California belonged to Mexico.

There were thirteen million people living in the United States in 1831. Eleven million of them were white, two million were African American, and 330,000 were aboriginal Native American. Most of those African Americans were slaves in the South. Both whites and African Americans had been increasing in numbers; their combined population had doubled in less than twenty years. As a result, many whites, and, in the south, their attendant black slaves, had moved from the settled areas of the East to cheaper, more fertile lands between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. Native Americans, meanwhile, had been

Three-quarters of Americans lived on subsistence farms at this time, consuming most of what they grew and marketing the surplus nearby. But as roads and waterways were improved, more and more of these individuals turned to commercial farming, growing crops or raising livestock for shipment and sale at distant markets and buying food and other necessities for themselves and their families rather than growing or producing them. What they produced varied by region. In New England they raised sheep, in Ohio they grew wheat, in Tennessee and Kentucky they grew tobacco or corn and raised pigs and cattle, and across the South they grew cotton. In all of these regions, farmers found that they could achieve a better life through commercial farming than they had experienced with subsistence farming.

It was improved transportationtransportation that was faster, cheaper, and more readily availablethat allowed these new commercial farmers to produce more, sell more, and buy more. The earliest land transportation had been conducted over the Indian trails that connected villages and crossed streams at fordable shallows. Settlers soon improved these trails by widening them into wagon roads. These roads were primitiveoften consisting of little more than stakes marking the way across open areas and cleared forest paths littered with one-foot-high tree stumpsbut they enabled hundreds of settlers to first move west and then ship their produce back east.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.