A merican railroading spans nearly two centuries. This intricate and complex network has made for fascinating and endless study. As railroads emerged, evolved, and matured, numerous companies provided a great variety of services to points across the continent. Railroads grew rapidly to become the predominant form of American transport in the nineteenth century because they offered greater speed, capacity, and efficiency than other modes of transportation. American railroads thrived as a result of the nations underdeveloped road network and an intense desire for transport to interior points. Prior to the railroad, American commerce relied largely on waterwayscoastal shipping, river navigation, and, to a limited degree, manmade canalswhich reached most established population centers. Yet commerce beyond these corridors was slow, difficult, and costly. Railway construction faced a host of hurdles in its infancy, but once its advantages were clearly demonstrated, the mode was unstoppable and railway construction took off at an unprecedented rate. Thousands of railroad schemes were formulated and innumerable companies chartered. Some railroads were immediately successful. Others progressed slowly, while some faltered and many remained little more than stillborn visions. By the early twentieth century, railway lines connected virtually every population center in North America. Competitive interests produced numerous parallel schemes that vied for traffic. As a result, most major cities were served by two or more railway systems.

Using its domestically built Best Friend of Charleston, South 15, 1831. The locomotive was destroyed in a boiler explosion a few months later. At the 1939 New York Worlds Fair, Carolina Canal & Rail Road introduced Americas first scheduled steam-hauled passenger service on January k Worlds Fair, a replica of the Best Friend is demonstrated alongside the William Mason, a 4-4-0 locomotive typical of the mid-nineteenth century. H. W. Pontin photo, Solomon collection

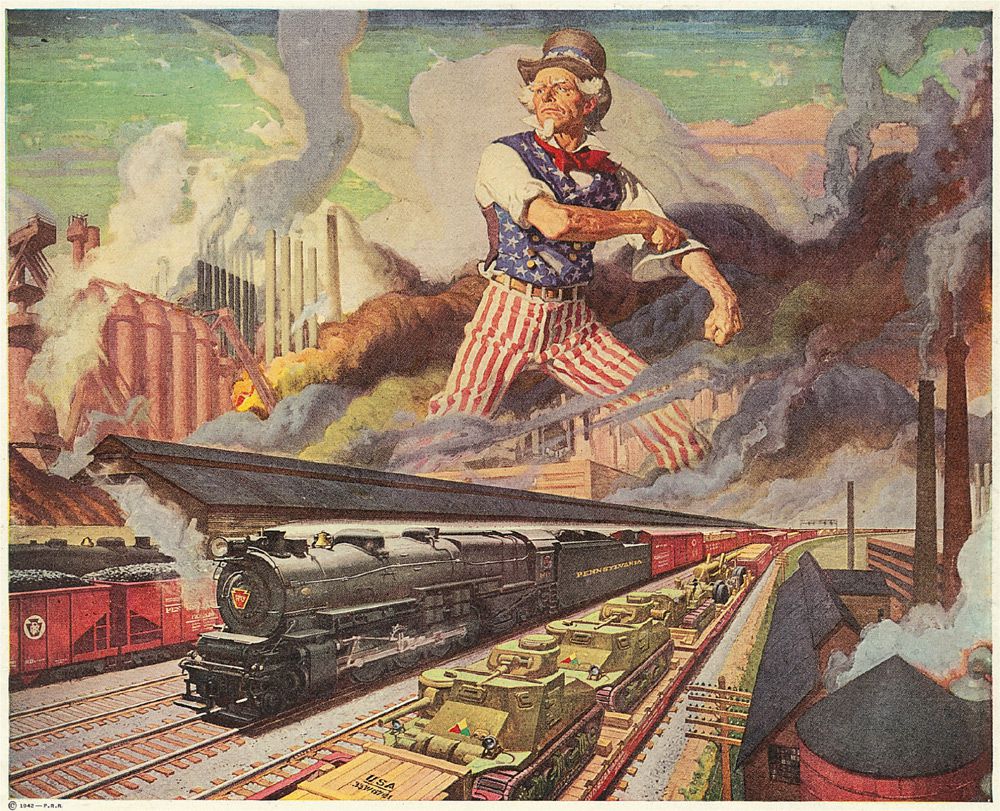

Most primary routes were in place by 1910, and while construction of new lines continued on a limited basis into the 1930s, the network reached its zenith in the 1920s. The growth of government-sponsored highways, combined with inexpensive petroleum, fostered automotive industries that eroded railway traffic. While railroads initially favored highway development, viewing improved local roads as feeders to their lines, the tide quickly changed, and as early as 1916 railroads were feeling the pinch of highway traffic. By the 1930s, highways had dramatically affected business. Highway competition, strict rate regulation, and inflexible labor arrangements caused the whole industry to stagnate and then contract. During this transition, railroads evolved from general-purpose transportation networks to primarily bulk-freight transport systems. As railroads became more specialized, they withdrew from public consciousness. Yet deregulation in the 1980s, combined with rising fuel prices and improvements to railroad technology, have facilitated a railroad renaissance for freight and, to a limited extent, passengers.

In the course of this 200-year history, railroads have undergone a multitude of changes, some subtle, some dramatic. Companies have come and gone, and most railroads operating today are the result of waves of mergers and consolidations, spin-offs, and reorganizations. Every railroad has a unique history, and while generalizations can be applied to the industry as a whole, to understand the particulars of an individual railroad, a careful examination of its background is necessary.

THE FORMATIVE YEARS

The railway originated in Britain. The technology evolved in the early nineteenth century, from simple animal-drawn tramways serving collieries and quarries to steam-powered common carriers. Steam locomotives developed from stationary pumping engines into efficient pulling machines. The opening of George Stephensons Stockton & Darlington railway in 1825 established a prototype for most later railway development and quickly attracted the attention of American engineers and entrepreneurs. Stephenson further refined the railway concept with his Liverpool & Manchester line that opened in 1829. These early railways combined locomotive haulage with a fixed-railed tramway, connecting established population centers and carrying both people and freight on a scheduled basis for published rates.

Early railways sought improved efficiency. This sparked Liverpool & Manchester to hold a locomotive competition with a view toward producing more effective and more powerful locomotives. Interestingly, George Stephensons son, Robert, produced the winning locomotive, a cleverly designed machine called the Rocket that attained a top speed of 29 miles per hour, extraordinarily fast at the time. Combining the three principal elements of a successful locomotivea multi-tube (fire tube) boiler, forced draft from exhaust steam, and direct linkage between the piston and drive wheelsthe Rocket rendered all other designs obsolete and set the pattern for most future steam locomotive designs, not just in Britain, but in the United States and around the world.

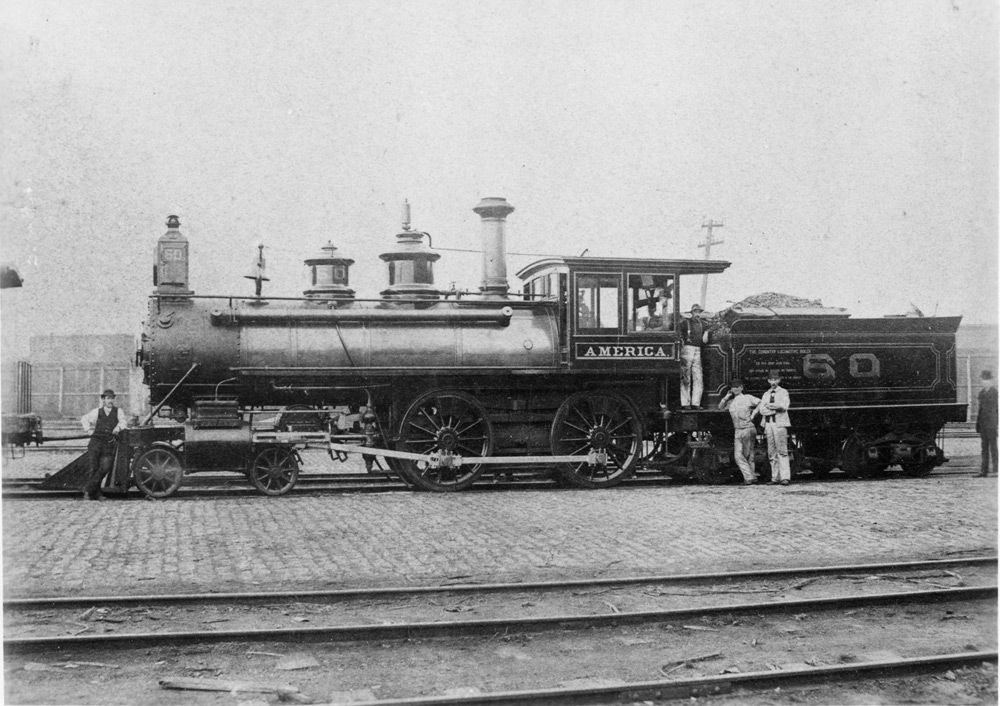

The classic 4-4-0 wheel arrangement was by far the most common in North America in the second half of the nineteenth century, with many railroads continuing to use them well into the twentieth century. While the wheel arrangement was standard, there was considerable variation in other elements of 4-4-0 design. The America, pictured here (later Monons No. 109), was an experimental type with an unusual Coventry boiler. Solomon collection

The tracks were barely in place on the Stockton & Darlington when the concept was exported to the United States. America was ripe for railway development. Prior to the British pioneers, American visionaries had been agitating for railways. As in Britain, the first American lines were industrial tramways. In Quincy, Massachusetts, Gridley Bryant built a 3-mile line to move granite from a quarry to a pier, while in Pennsylvania, coal-hauling tramways were built to move mine products to canal heads.

Most significant of the early lines was Delaware & Hudson (D&H), which as early as 1825 had considered a railway to augment its canal. D&H planned to move anthracite coal from mines at Carbondale, Pennsylvania, to New York City. In January 1828, the companys chief engineer, John B. Jervis, dispatched engineer Horatio Allen to Britain to learn about railway practice and to purchase both iron rails and complete locomotives for import to the United States. As built, D&Hs 17-mile-long railway connected Carbondale with the canal head at Honesdale, Pennsylvania, using a mix of level sections, where coal wagons were horse-drawn, and steeply inclined planes that were hauled by cables drawn by stationary engines. History was made on August 8, 1829, when Allen fired up Foster, Rastrick & Companys