IMAGES

of Rail

EAST TEXAS

LOGGING RAILROADS

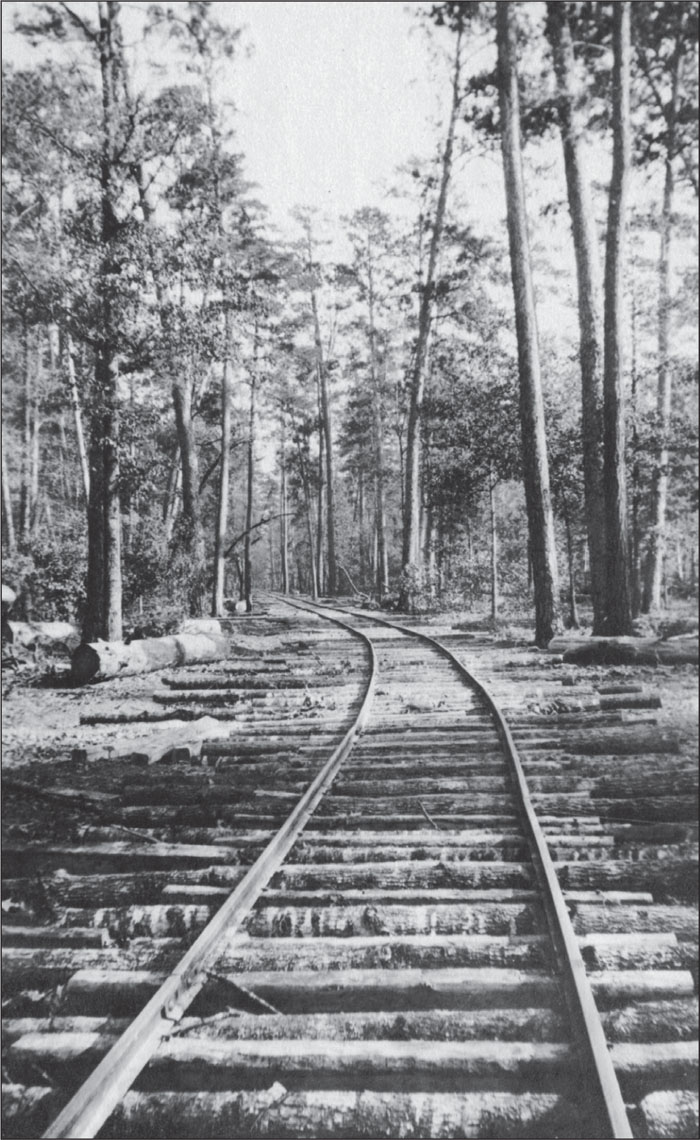

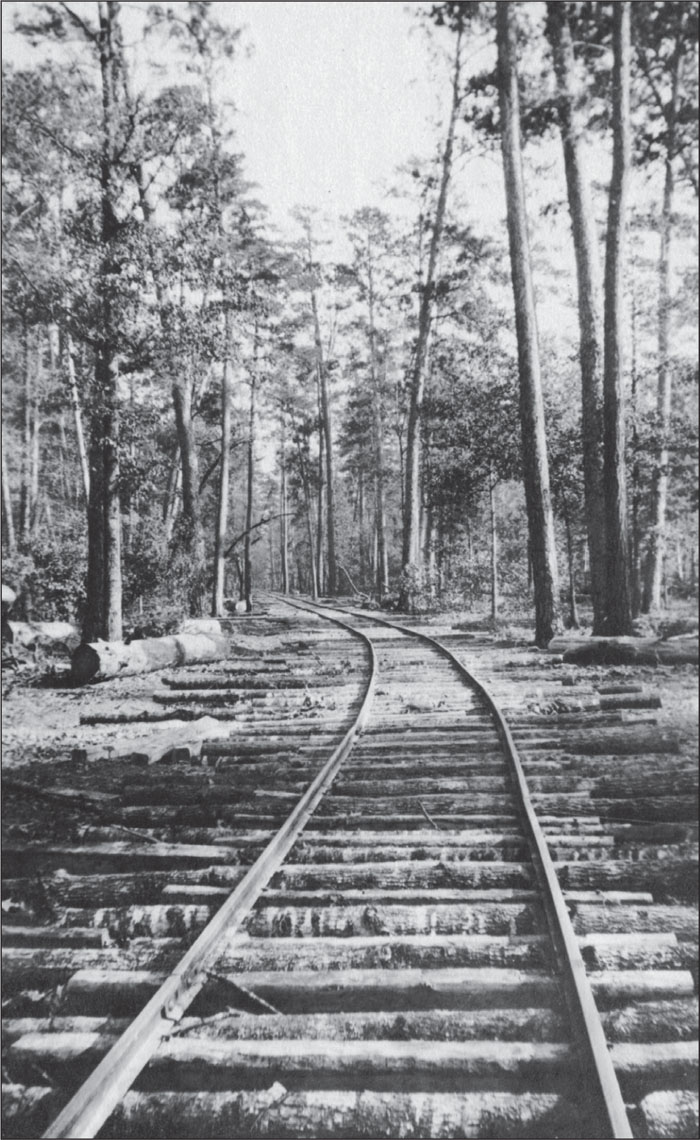

This unknown stretch of tram railroad was photographed by a traveler headed through East Texas in the 1920s. Crossties made out of small tree trunks were cut to widely differing lengths with no attempt to remove the bark. The construction practices displayed were typical of trams all over Texas during the heyday of logging. (Courtesy Texas Transportation Archive.)

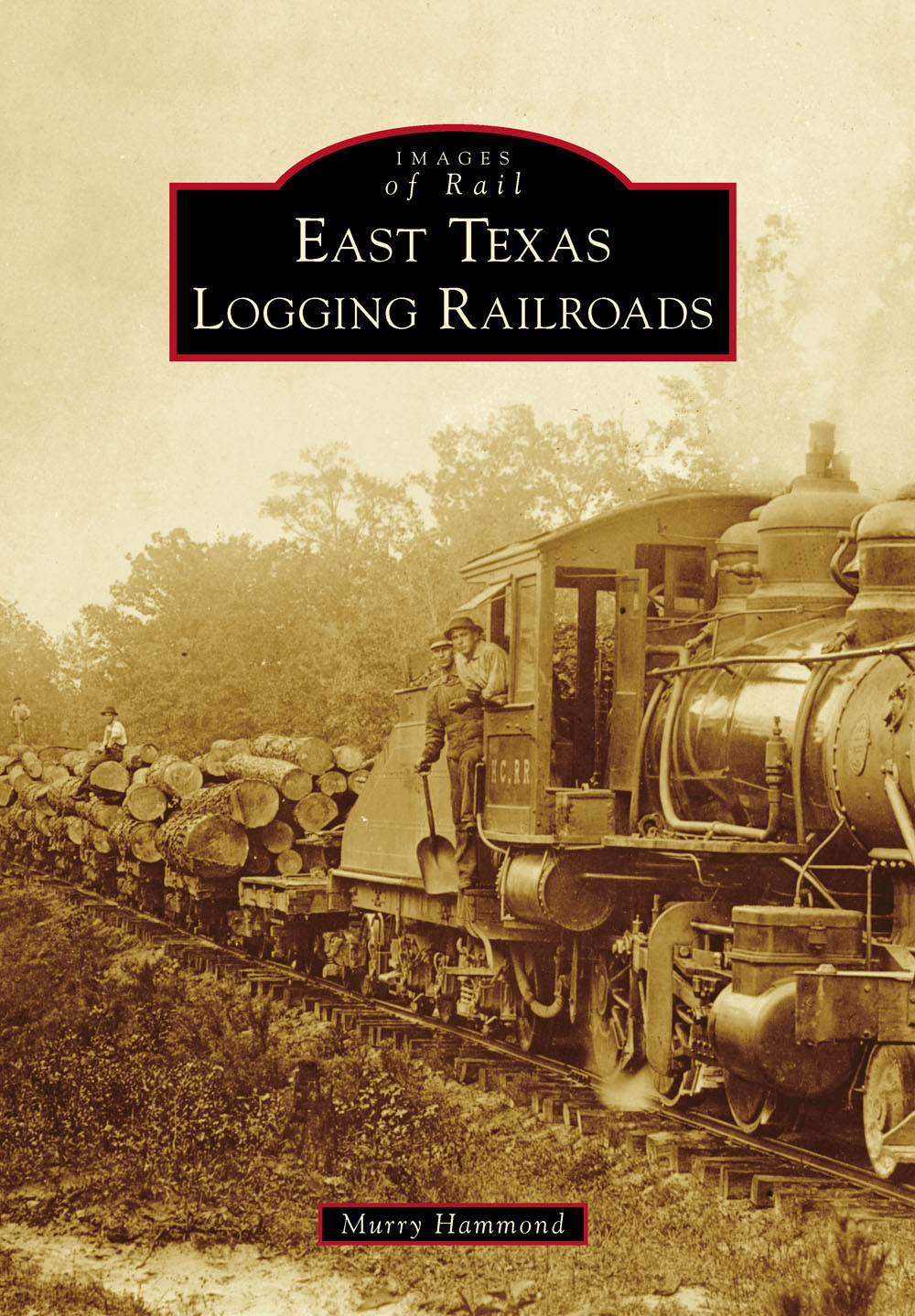

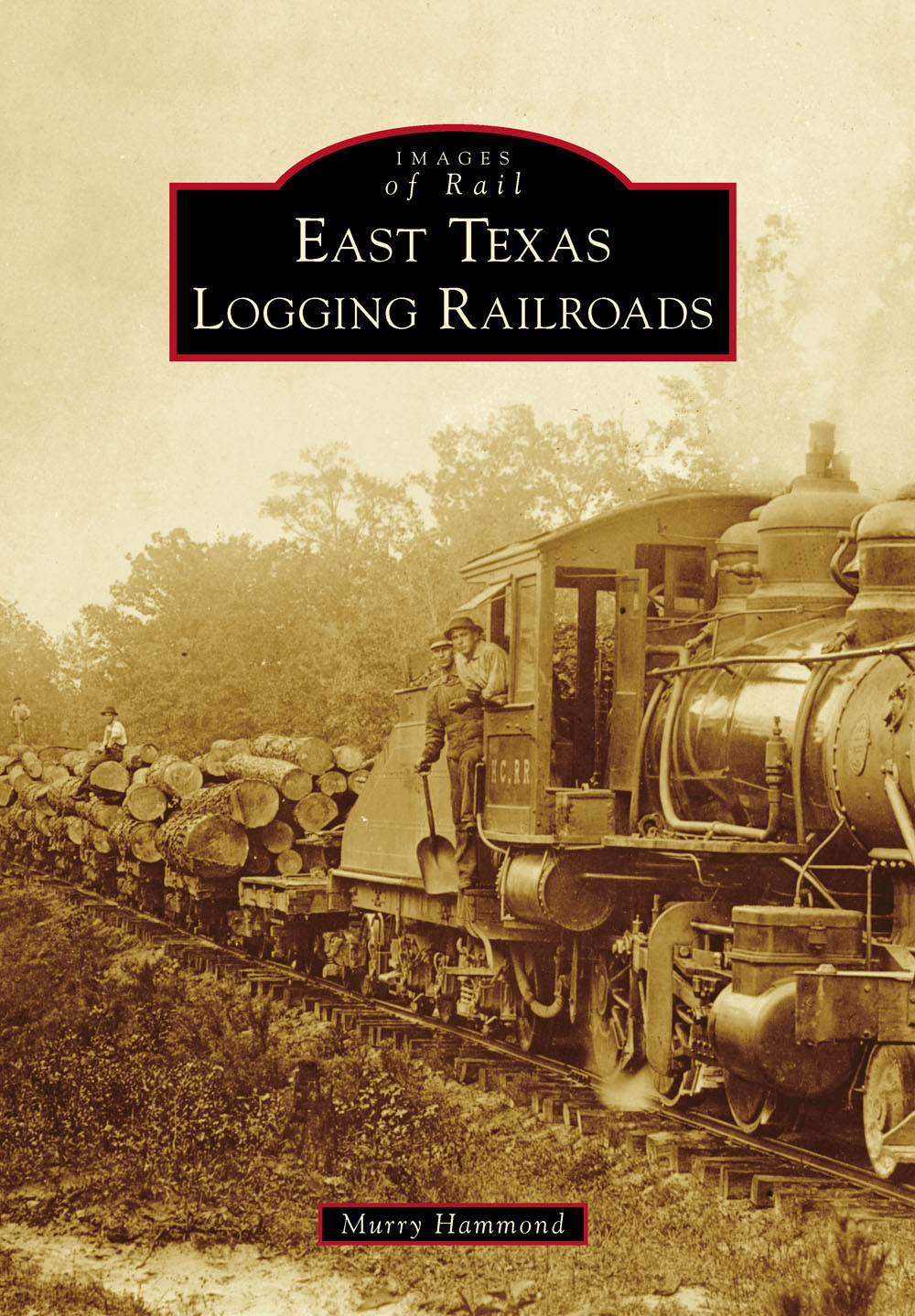

ON THE COVER: Houston County Railroad Locomotive No. 5 pauses mid-trip in 1915 on its way to the 4-C mill at Kennard, Texas. Houston County Railroad was a name given to trams that branched off the short-line Eastern Texas Railroad. When the mills closed in 1917, the No. 5 went to Peavy-Byrnes Lumber Company at Kinder, Louisiana, then to Peavy-Moore Lumber Company at Deweyville, Texas, where it operated into the 1940s. (Courtesy Texas Transportation Archive.)

IMAGES

of Rail

EAST TEXAS

LOGGING RAILROADS

Murry Hammond

Copyright 2016 by Murry Hammond

ISBN 978-1-4671-1574-2

Ebook ISBN 9781439655887

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015948605

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

For the people of East Texas and all who love its history.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The people of East Texas are warm and generous by nature, and I have long been the grateful recipient of their willingness to share history. Richard Moody, Bob and Edna King, and Joan Weatherly have all invited me into their homes. Theyalong with Jack Langston, Mary Kirby, Ruel Young, Bob Bramlett, and so many others over the yearshave contributed their stories and precious photographs to these pages. I am deeply grateful to you.

The institutions and libraries that opened up their collections were no less wonderful. Grateful thanks go to Kaitlin Wieseman and Kendall Gay at the Texas Forestry Museum, Tim Ronk at the Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Serena Keech at Stella Hill Memorial Library in Alto, Melissa Booker and Pearl Phillips at the Kirbyville Public Library, Renee Hart Wells at the Hardin County Museum, Kathy Knighton at the Newton County Museum, John Anderson and Halley Grogan at the Texas State Library and Archives, and all the staff at Jasper County Archives and Museum. At Arcadia Publishing, Samantha Langlois got me started, and Sarah Gottlieb took me the rest of the way through my project. Sarahs advice was always so helpful and welcome.

Special thanks go to Jonathan Gerland at the History Center at Diboll for his help, counsel, and friendship. Rail historian Lester Haines is a treasured friend who was beyond generous in the contribution of his own images and those from the Keeling Collection that he lovingly maintains. Finally, thanks to my most significant other and talented editor, Anne Crawford, who more than once has prevented my grammar from standing in the way of a good caption.

INTRODUCTION

The southern forest was once a stand of virgin timber that stretched unbroken from the Atlantic Ocean to its far western edge, the old-growth forests of East Texas. Pines were dominantespecially the longleaf, shortleaf, and loblolly varieties. Cypress grew along rivers, as did hardwoods such as oaks and gums. In all, merchantable timber covered 36,000 square miles across 48 East Texas counties, an area the size of Indiana.

The first industrial-minded lumbermen came mostly from northern states. They taught themselves by trial and error the methods of efficient logging as they worked the great eastern white pine forests of New England and the Great Lakes. As those regions were exhausted of their timber stands in the 1870s, the lumbermen brought their expertise, drive, and capital to the southern forests.

Up until this time, Texas lumbering had taken the form of local operations that harvested timber adjacent to tiny mills. Rivers were utilized where timber could be floated, and larger mills were established along the coast at the mouth of these rivers. For the most part, however, much of the forest was hard to reach, the mill output was small, and the markets remained entirely local. The yield simply could not keep up with the increasing demand for Texas lumber. This was the extent of the Texas lumber industry until railroads penetrated the region, connecting commercial centers with each other and with the world beyond.

The first significant infiltration by rail into the heart of the longleaf belt was by the Houston East & West Texas Railway (HE&WT), which began construction in 1876 and completed a route to Shreveport, Louisiana, in 1886. On the Texas side, the HE&WT (locally nicknamed the Hell Either Way Taken) traversed some of the densest sections of East Texas forest. Dozens of mill towns emerged along its route, and some, such as Lufkin in Angelina County, would be counted among the most important lumber centers in the South.

Elsewhere in East Texas, a surge of new railroad construction was happening. The Texas & Pacific Railway completed its east-west line through the northern section in 1873 at the same time that the InternationalGreat Northern Railroad was building northward from Houston along the forests western edge. The Sabine & East Texas Railway completed its route northward from Beaumont through the densely forested border counties, while numerous smaller but significant lines were filling in the railroad map with branches and bridge routes across every county that offered merchantable timber.

By the end of the 1880s, there was no longer a point in East Texas that was not within a tramlines reach of either a rail outlet or a navigable river. Large-scale harvesting of forests was now a possibility waiting to be exploited, and lumbermen from all over the United States answered the call. Some of these early entrepreneurs were able to raise enough capital to purchase huge sections of timber, while others established themselves with only moderate amounts of capital and timberland, and still others manufactured on a small scale, utilizing only lands in their immediate vicinity. All built sawmills, and many built railroads.

To maximize output, mill owners built their own industrial tram railroads, greatly extending a mills reach into remote forestlands. The first trams were animal-powered: small carts pulled over short distances on wooden rails to feed logs into one of the rivers that connected with the coastal mills at Beaumont and Orange. The first steam locomotive to be used on a Texas tram was brought up the Neches River in 1878 and used on the Yellow Bluff Tram, a wood-railed line that extended eight miles from a point on the Neches River near modern-day Evadale to a logging camp at Cairo Springs. The Yellow Bluff Tram engine was able to pull a whole string of log cars with exponentially less energy and expense than older methods.

The success of the Yellow Bluff inspired others to adopt its model, and soon steam engines, iron rail, and heavier logging equipment began to arrive along the new railroads and rivers. In the 1870s, there were less than 10 trams of any variety operating in Texas, but by the end of the 1880s, that number increased to more than 70nearly all of which were built along recently constructed rail lines. Large mill towns like Call and Deweyville in Newton County and Village and Olive in Hardin County were established during this time.

Next page