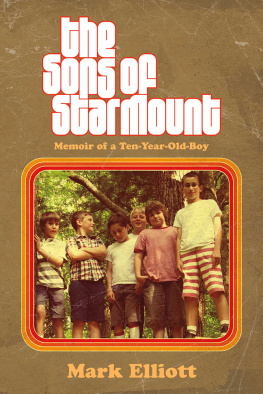

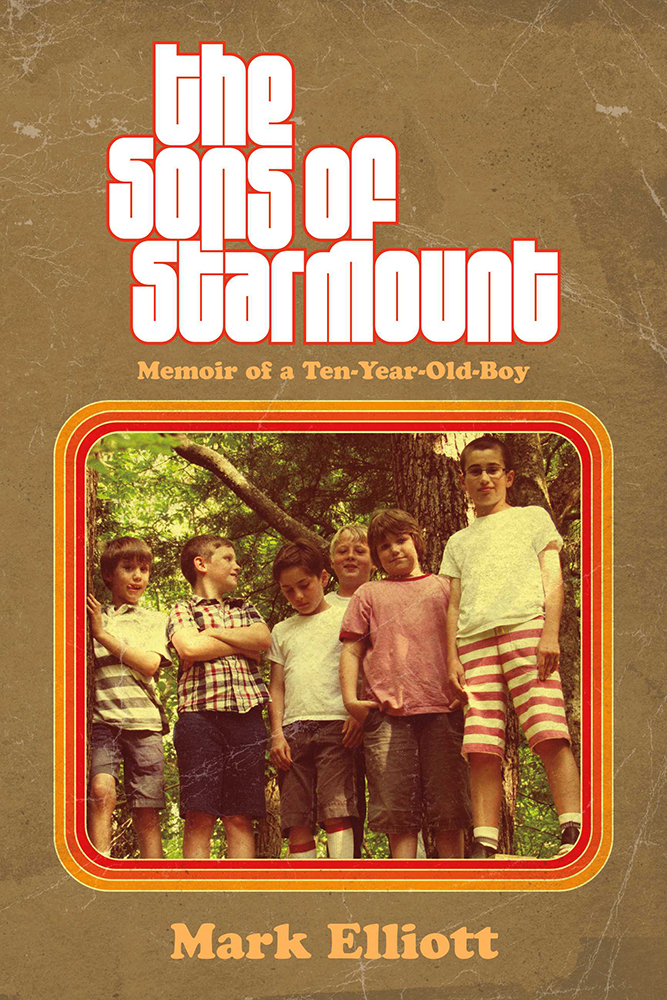

The Sons of Starmount: Memoir of a Ten-Year-Old-Boy

Copyright 2019 by Mark Elliott

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Publishers Note: Although this is a work of non-fiction, some character and locale names have been changed.

ISBN (Print): 978-1-54395-794-5

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-54395-795-2

for my father

Dr. C. Courtney Elliott

Chapter

The Boys

Your best friends are waiting in the rendezvous tree

At the edge of the wild wood by a bottomless creek

Come on and get your feet wet now

Weekend Runaways

I remember Starmount like a reincarnated soul remembers a past life. Memories begin as involuntary neural firings, dj vu moments you just cant seem to hold on to. But they dont give up on you. They come back for more. They are not surface memories, like the kind you thumb through in dusty photo albums, or the ones springing forth from the bottom of a water-stained cardboard box after you cut the old, yellowed masking tape free. And they certainly are not throwaway party pieces for you to use in one of those hackneyed remember-when conversations. They are deeper than that. They are the marrow memories. The ones connecting blood, bone, and soul. And for me, they are the lifeline back to a time and place I apparently have no interest in leaving behind.

I am older now, in fact, forty years older than I was when those marrow memories were born. Wrinkles have replaced freckles, and thinning strands of gray hair have all but pushed out the roots of a once red clay-colored, bowl-cut mane. From outside appearances, I fear I may be utterly unrecognizable to that ten-year-old boy. But on the inside, I am his doppelgnger. And like water from another time, senses flood my brain as they did in 1977. Primed with the memories of yesterday, I can still feel, hear, see, and smell my life on Starmount.

I can feel the tingling mix of dewy grass and spongy earth beneath my feet, and the sharp tug of an eight-pound-test fishing line against the inside knuckle of my left index finger. I can feel yesterdays wind warm across my face as I charge through clouds of katydids and dragonflies at full pelt through a knee-high August field.

I can hear the grinding of steel skateboard wheels giving way to their failed bearings as they careen over the hot blacktop. At a distance, those wheels sound like the rattling of old boxcars heading to places I have never been. And when everything else is quiet, I can hear the low croaking of bullfrogs, the heartbeat of the south, echoing in the humid night air, and best friends calling my name.

I can see a metallic-blue streetlight bouncing around in my minds eye, like some magic orb bleeding Halloween shadows through the October woods. Sometimes I stare into a rain-filled parking lot puddle like it was a wishing well. And when I do, I swear I can see the roiling green water just above a largemouth bass that has overconfidently taken my bait. And always, probably because Ive grown one of my own now, I see my fathers doctoral school beard, dangling like Spanish moss in the live oak trees.

I can smell a faint whiff of sweet honeysuckle blown about by butterfly wings as it slips away on a mightier magnolia breeze. And just as sweet, at least to me, I am randomly overtaken by the musty smell of a dew-soaked sleeping bag inside a mildewed canvas tent, or the bubbling-up of methane and crawfish as my bare feet pierce a mud-bottom creek. Hmm. Who said that you can never go home again?

I arrived on Starmount Drive as an only child, but by weeks end, I had brothers. The year we spent together fishing knee-deep in alligator ponds, kicking down shaded forest paths, and riding tire-swing time machines beneath century-old live oak branches allowed us a degree of childhood autonomy, now lost to the ages. Flanked by a few important months either side of my tenth birthday, I consider 1977 to be the most soul-defining year of my life. Through countless adventures, mishaps, and life-affirming realizations, my friends and I became the vagabond children of a new family. A family mothered by soft green fields, warm waters, and the random flicker of fireflies. Her perfume smelled of loblolly, honeysuckle, and chewing gum. We were a family fathered by screeching bike tires, whistling mud balls, and seventies songs. His cologne smelled of frog guts, wet sneakers, and peanut butter. We were the perfect mix of those two spirited lovers. We were, and will always be, the Sons of Starmount.

Jim Maples bounded down the embankment between his house and mine wearing oversized brown Dingo boots, mud-splattered camouflage pants, and a shirt with blood-red streaks of Kool-Aid down the front. He looked like a cross between G.I. Joe and a murder victim. Holding a fishing rod in one hand and a big burled stick in the other, Jim uttered his first greeting to me like youd flip a baseball underhanded to an old friend: Hey! This stick is for catching snakes. Wanna go fishin?

I didnt know whether he meant fishing for rattlers or largemouth, but I didnt care. He was selling adventure and I was buying. We became instant best friends, connected first by the hill between our houses, and only minutes later by a shared longing for everything wild, and a restlessness beyond our years. We were separate halves of the same boy. We complemented each other like a left boot does the right. We walked beside each other mostly, and then took turns leading the way, and in those rare moments when we stepped on each other, well, we both fell down.

As we walked the well-worn path through the field toward Alligator Pond, careful not to step on the stinging nettles with our bare feet, he told me everything he knew about snakes, especially the kind that could kill you. And what he knew about snakes blew my mind. All of em, except for the coral snake, have arrow-shaped heads, and you better grab em right behind the bony part or theyll twist their heads around and get you right there, Jim said with half a smirk, pointing to the fleshy part of his hand near the thumb.

Not to be outdone, I blew his mind with everything I knew about what hides in the shadows and lurks beyond our sight, like the Loch Ness Monster, aliens, and my favorite obsession, Sasquatch.

Its out there, man, Im tellin ya. Famous hunters have been looking for him for years. But you and me, Jim, were gonna find him firstback there, I said, pointing wildly toward the dark woods, far beyond the point where the large live oaks in the field gave way to the taller loblolly pines.

Feeling an instant and reciprocal appreciation for the absurd, we never once considered questioning each others stories, no matter how far-out the subject matter or exaggerated the delivery. Together, we stirred up chaos like the occasional Panhandle dust devil stirred up the red clay beneath our feet. Jim was fearless, always the first to dive headlong into the tall weeds to catch a snake and the last to care about what kind of snake it was. More important to me, he never blinked an eye at whatever ridiculous plan I put forth. It seemed alright with him as long as he was part of it.