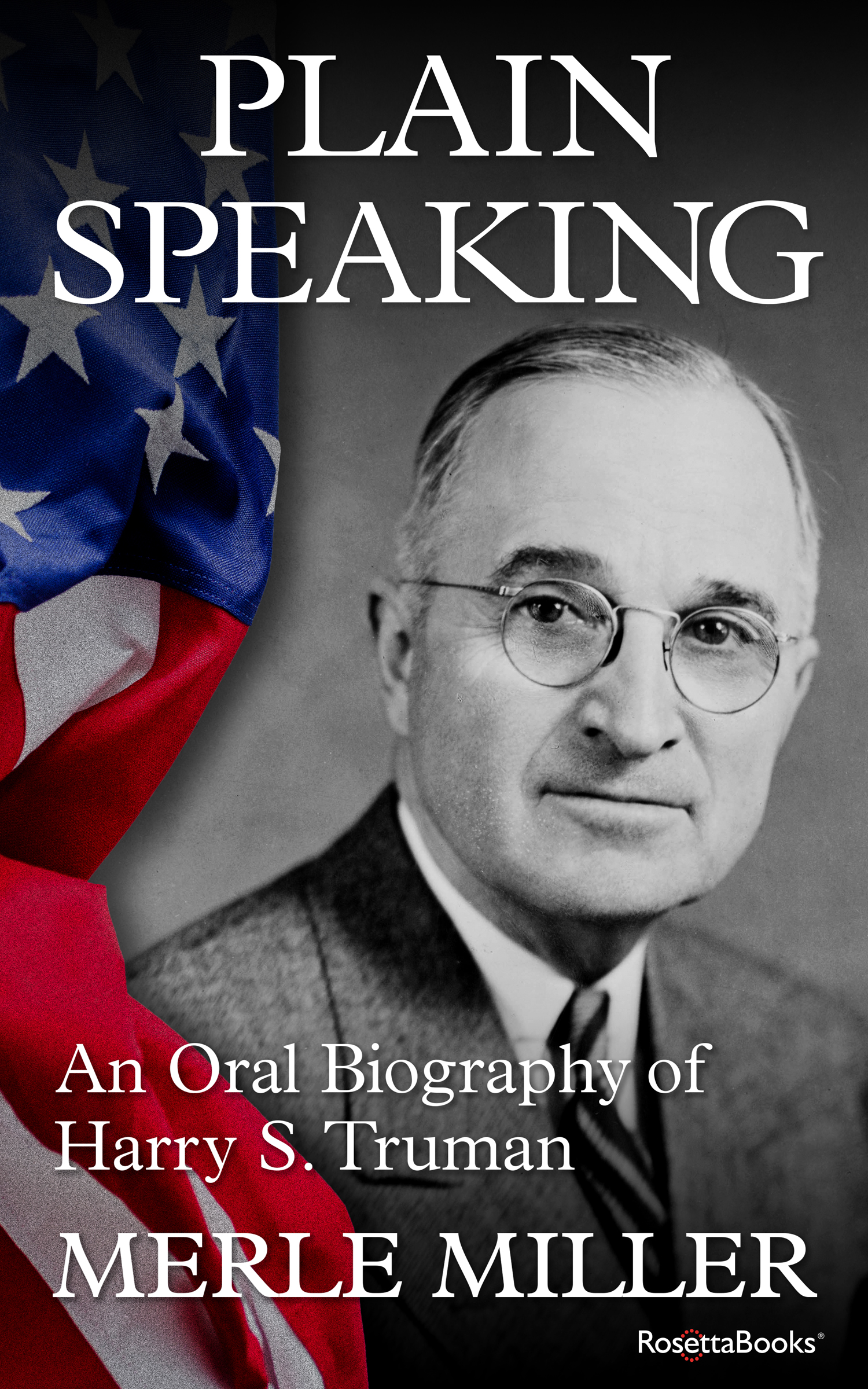

Plain Speaking

An Oral Biography of

Harry S. Truman

Merle Miller

Plain Speaking

Copyright 1974 by Merle Miller

Cover art and Electronic Edition 2018 by RosettaBooks LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Cover jacket design by Lon Kirschner

ISBN e-Pub edition: 9780795351280

For David W. Elliott, who has been urging me to do this book for almost ten years now, who became as familiar with and as fond of Harry Truman as I am and who, when the time came, did more than half the work and deserves more than half the credit.

Also for Judy Freed, who insisted that I do it and even found a publisher.

And, of course, for Robert Alan Aurthur and David Susskind, without whom I would never have met Harry Truman or any of the other people who inhabit these pages. They are mostly gone now, and I miss them.

CONTENTS

For, the noblest deeds do not always shew men's virtues and vices, but oftentimes a light occasion, a word, or some sport makes men's natural dispositions and manners appear more plain, than the famous battles won, wherein are slain ten thousand men, or the great armies, or cities worn by siege or assault.

PLUTARCH, Alexander the Great, i

A NOTE ON THE LANGUAGE

THE diligent reader will notice that sometimes Mr. Truman is quoted as saying "fella" and sometimes "fellow," that sometimes he confuses "like" and "as" and sometimes does not, and that while he usually has "dinner" at twelve noon, he occasionally has "lunch" at that hour. There are other inconsistencies. Mr. Truman talked that way, inconsistently, like the rest of us.

He was a self-educated man, and he mispronounced a reasonable number of words, which in the beginning puzzled me. Then I realized that while he had often read them, he had seldom, if ever, spoken them aloud, not even in many cases heard them spoken aloud. It's like that if you're one of the few readers in town.

PREFACE

IT HAS been good to think about Harry Truman this spring and summer, the twentieth summer since he left the White House, the summer after his death, the summer of Watergate. The memory of him has never been sharper, never brighter than it is now, a time when menacing, shadowy men are everywhere among us.

There was never anything shadowy about old Harry, never anything menacing. He was never less than four-dimensional; he was always a person, a human being.

I once wrote that Harry Truman might be the last human being to occupy the White House, and considering, as he would say, "the four fellas that succeeded me," I see no reason to change my mind.

As you will see in reading this book, Harry's words were never fancy, but they were never obscure either. You never had to try to figure out what Harry was up to; he told you what he was up to. And, as they said of him back in Independence, he was a man of his word. There was not a duplicitous bone in his body. He was without guile, and when it was all over, when he and Bess came back home, after eighteen years in Washington, more than seven of them in an unbugged,President were, to state it gently, strained, he and Bess might have to walk from the White House to the railroad station. Or perhaps take a taxi.

"But that wouldn't have bothered me," he told me years later. "I was there more or less by accident you might say, and I just never got to thinking that I was anything special. It's very easy to do that in Washington, and I've seen it happen to a lot of fellas. But I did my best not to let it happen to me. I tried never to forget who I was and where I'd come from and where I was going back to. And if you can do that, things usually work out all right in the end."

As nearly as he could remember, Harry's last act in the White House was returning a pencil or maybe it was a pen to the desk of the man he had borrowed it from.

"Everything," he said, "all of it belongs to the people. I was just privileged to use it for a while. That's all. And since it was only lent to me, and by that I'm includin' the power of the Presidency, such as it is, I had to try to use whatever it was with great care so that I could pass it on to the next fella in the best condition possible. And for the most part I think you can say I succeeded."

Mr. President, it's been said that the Presidency is the most powerful office in the world. Do you think that's true?

"Oh, no. Oh, my, no. About the biggest power the President has, and I've said this before, is the power to persuade people to do what they ought to do without having to be persuaded. There are a lot of other powers written in the Constitution and given to the President, but it's that power to persuade people to do what they ought to do anyway that's the biggest. And if the man who is President doesn't understand that, if he thinks he's too big to do the necessary persuading, then he's in for big trouble, and so is the country."

So Harry and Bess took the train back to Independence, and people in Independence found them unchanged; it was as if they had never been away, and as a neighbor says in this book, maybe Harry never really left Independence; maybe he just sort of commuted to Washington.

Anyway, people back home found that they were as Bernard Berenson, yes, Bernard Berenson, said, "Both as natural, as unspoiled by high office as if he had risen no further than alderman of Independence, Missouri."

And you remember the day after Mr. Truman got back home, he took his usual morning walk, and Ray Scherer, the television reporter, asked him what was the first thing he did when he walked in the house at 219 North Delaware the night before, pausing for some monumental statement suitable for engraving on the side of Mount Rushmore.

"I carried the grips up to the attic," said Harry.

That house on North Delaware Street had served as the summer White House various times during the more than seven years that Harry Truman was President, but somehow it never occurred to him to have it all fancied up at the expense of the taxpayers. In fact, he didn't even own the place. He and Bess had put up with mother-in-law Wallace from the time of their marriage in 1919 until her death in 1952. They had fed her and clothed her and housed her, including in her last years a room of her very own in the White House. But Madge Gates Wallace never stopped ruminating, aloud and whenever possible in the presence of her son-in-law, about all the people who would have made better Presidents than Harry. And why did he have to fire that nice General MacArthur? The general was a man she could have felt socially at ease with; for one thing, he was a gentleman to the manor born. He was a five-star general, not like some dirt farmers who shall be nameless. And don't track up the kitchen with your muddy feet, Harry.

When she died, that impossible old woman, she didn't even leave the house to Harry. She left it to Bess and the Wallace boys, and Harry had to buy out their share.

But, as it says in these pages, in all those years, Harry never once complained. He never once answered back. Mrs. W. L. C. Palmer, who taught him Latin and mathematics, says, "You must remember Harry is a reticent man."