This book made available by the Internet Archive.

I dedicate this book to the Beavers.

To 'Scrooge', my beloved Mother, the most wonderful woman. I owe my survival to her.

To 'Petit Pole', Myriam, my adored sister, whose courage I salute.

To 'Mounch', Raouf, my brother and my friend, my support, my example of dignity.

To 'the Negus', my sister Maria, who gave me the opportunity to begin my life over again in the country of democracy. Thank you.

To 'Charlie', my very talented sister Soukaina, in whom I have faith.

To 'Geo Trouvetout', Abdellatif, my young brother, who inspired me with the strength to fight and hope.

To 'Barnaby', Achoura, and 'Dingo', Halima, for their loyalty through every ordeal.

To 'Big, Bad Wolf, my beloved father, who I hope is proud of us.

To Azzedine, my uncle, and Hamza, my cousin, who died too young.

To the children of the Beavers, Michael, Tania and Nawel, my nephew and nieces. May this account not prevent them from loving their country, Morocco.

M.O.

To my daughter Lea, who was constantly in my thoughts as I listened to this story.

M.F,

\

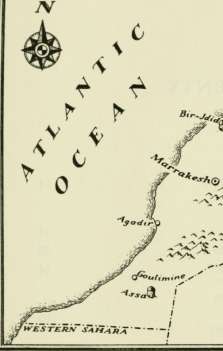

n*f*

^O^^'

d^.

- esctMp^ r-outm

lOOmtlfs

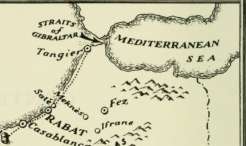

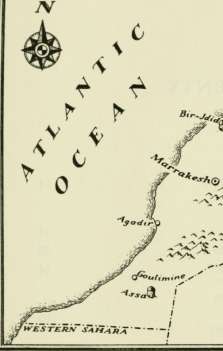

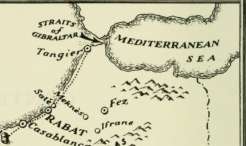

MOROCCO

PREFACE

Why this book? It is clear that even if we hadn't met by chance, MaHka Oufkir would have written this account one day. Since her escape from prison, she has always wanted to tell her story and exorcize the painful past that continues to torment her. The idea was slowly forming in her mind, but there was no hurry. She wasn't ready yet.

Why write it together? That is also clearwe had a helping hand from fate. We met by chance and immediately became friends, which gave her the courage finally to unburden herself, and prompted me to shelve all my other plans to listen to her and transcribe her account.

We met for the first time in March 1997, at a party to celebrate the Iranian new year. A mutual friend pointed out a sHm, pretty young woman lost in the crowd of guests.

'That's Malika, General Oufkir's eldest daughter.'

The name gave me a start. It evoked injustice, horror, the unutterable.

The Oufkir children. Six youngsters and their mother, incarcerated for twenty years in appalling Moroccan gaols. I recalled snatches of newspaper stories. I was overwhelmed.

How can anyone appear normal after such suffering? How can they Hve, laugh or love, how can they go on when they have lost the best years of their Hfe as a result of injustice?

PREFACE

I watched her. She hadn't seen me yet. Her behaviour was that of someone used to sociaHzing, but her eyes revealed a barely disguised grief. She was in the room with us, yet strangely elsewhere.

I carried on staring at her with an intensity that would have seemed rude, had she only noticed me. But she had eyes only for her companion, clinging to him as if her life depended on it. At last we were introduced. We exchanged a few cautious platitudes about our respective countries, she being from Morocco and I from Tunisia. We were both trying to size each other up.

I observed her covertly all evening. I watched her dance, noticing the grace of her movements, the way she held herself erect, her solitude in the midst of all those people having fun, or pretending to. From time to time our eyes met and we smiled at each other. 1 was perturbed by this woman. At the same time, she intimidated me. I didn't know what to say to her. Everything sounded trite, pathetic. Questioning her would be intrusive. And yet I was already burning to know.

At the end of the party, we exchanged telephone numbers. At that time I was finishing off a collection of short stories due to be pubhshed the following May. I still had a few weeks' work ahead of me. I suggested meeting as soon as I had finished. Malika agreed, without abandoning her reserve.

Over the next few days I thought about her continuously. I kept seeing her beautiful, sad face. I tried to picture myself in her situation. Or at least to imagine the unimaginable. I was besieged with questions. What had she been through? What did she feel now? How do you return from the grave?

I was deeply moved by her extraordinary destiny, the suffering she had endured, and by her miraculous survival. There is only a year's difference in our ages. She was imprisoned in December 1972, at the age of nineteen and a half, the year when 1, with my baccalaureate under my belt, was starting my preparatory year at the Ecole des Sciences PoUtiques. I obtained my diploma and have since fulfilled my childhood dream of becoming a journalist, and then a writer. I have worked, travelled, loved and suffered, like everyone else. I have

PREFACE

two wonderful children. I've lived a full, rich life and had my share of experiences, sorrows and joys.

Throughout that entire time, she had been incarcerated with her family, away from the world, in horrendous conditions, her horizons limited to the four walls of her cell.

The more I thought about her, the more driven I was by a single desire, a mixture of journalistic curiosity, the excitement of the writer and pure human interest in this woman's extraordinary destiny. I wanted Malika to tell me her story, and I wanted to write it with her. I was gripped by this idea. To be honest, I was obsessed.

That week, 1 sent her my books as a friendly gesture, in the hope that they would convey my ardent wish. After I had finally delivered the manuscript of my short stories, I called to invite her to lunch.

On the phone, her voice was faint. She was finding it hard to settle in Paris. She had been living with Eric, her companion, for barely eight months. In 1996, nine years after her breakout from prison, the Oufkir family had finally been granted permission to leave Morocco, thanks to the escape of Maria, one of the younger daughters, who had sought poHtical asylum in France.

The affair had made a big splash. Maria's strained little face had appeared on TV, and shortly afterwards, again on the small screen, the French pubHc had witnessed the arrival of some of the family on French soil: Malika, her sister Soukaina and her brother Raouf Myriam, their other sister, joined them shortly afterwards. Abdellatif, the youngest, and Fatima Oufkir, their mother, still Hved in Morocco at that time, Malika told me over a lunch that went on long into the afternoon.

I Hstened to her, fascinated. Malika is a remarkable storyteller. A Scheherazade. She has a thoroughly oriental narrative style, speaking slowly in an even tone, building suspense, and gesticulating with her tapering hands for added effect. Her eyes are incredibly expressive; she swings from melancholy to laughter. At the same moment she is a child, a teenage girl and a mature woman. She is all ages rolled into one, but has not really lived through any of them.