In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Bringing this book to light has been a long and somewhat bumpy road, and without the encouragement, love, and support of many people it wouldnt have been possible. Thank you to my friends and family, who have seen me through the most difficult of times and have always been there to listen, give advice, or just sit with me.

Thank you to Howard Yoon for guiding me through this crazy process and believing the story I wanted to tell was worth telling.

I am forever grateful to Jenna Free, who spent countless hours helping me turn a bunch of scattered memories and stories in tattered journals into a book.

Thank you to Bob Free and Carolyn Corker-Free for the use of their beautiful Silica Ranch as a writing retreat.

Many thanks to everyone at Grand Central, especially Sara Weiss and Jamie Raab.

Thank you to the early readers of the manuscript: Athena Wickam, who has walked a similar path, your amazing spirit inspires me; Gina Hart for your lifelong friendship, diligent notes, and gentle but honest insight.

Thank you to my parents, Paul and Bindy Ugenti, for your unconditional love and support. Knowing you are always there no matter what has allowed me to soar. Thank you for your patience and for loving me enough to let me find my own way.

To my brother, Paul Ugenti, a willing travel partner who in the streets of Cambodia encouraged me to take the leap and has been cheering me on ever since.

Thank you to Alex Garwood for protecting me, carrying the heavy load, and granting me the time and space I so desperately needed.

To my sister, Christine Garwood, thank you for the endless phone conversations and a lifetime of unwavering encouragement and support.

And most important, to Joe Shenton, who in the midst of chaos just saw me. Thank you for your love and light, and for bringing three beautiful boys and endless possibility to my life. I love you.

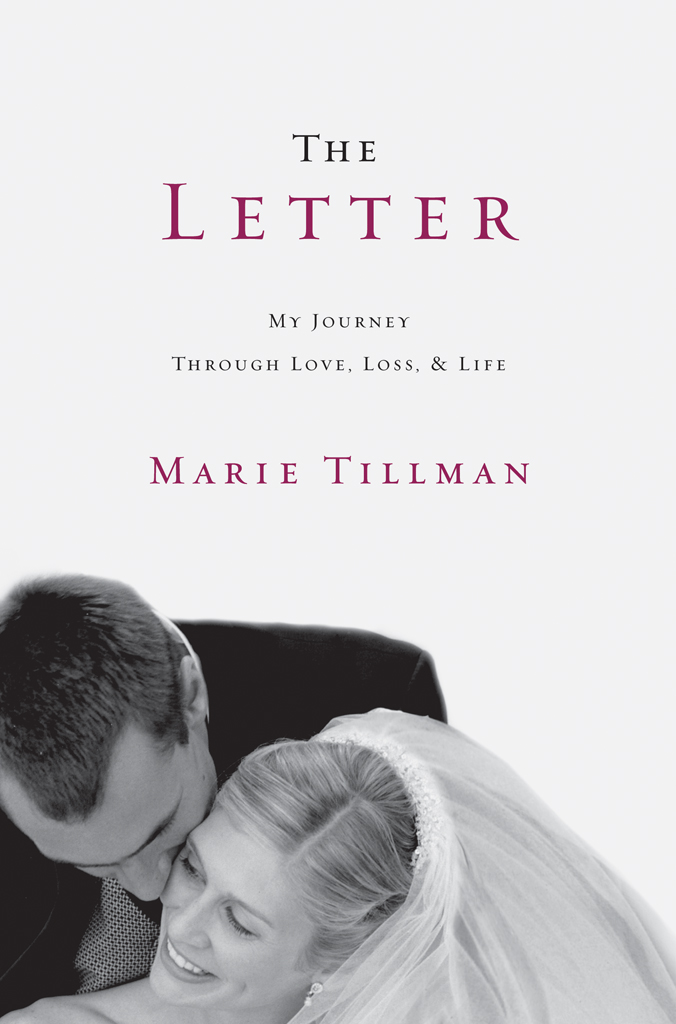

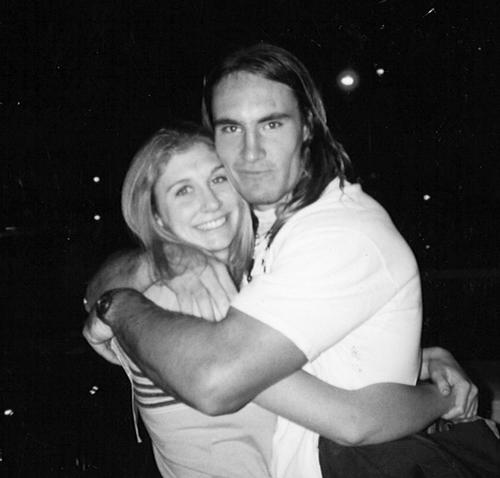

Many people in my life were surprised to hear I was writing a book about my experiences. The person I was in 2004, when my husband, Pat Tillman, was killed, would be more surprised than anyone.

When Pat died, the media and the public at large became fascinated with his story. His image was everywhere, and it seemed like everyone had something to say about why he left an NFL career to enlist in the military in the first place, or what his death meant. His biography was told and retold; clips from his college and NFL careers were broadcast again and again. So much of his life was out in public, and the things that were minethe details of our life together, and how I was coping with the loss of himI wanted to keep close. I wanted to keep something for myself. I also felt fearful that if I shared my memories, somehow theyd evaporate. Theyd float out of my mouth, into the atmosphere, and be gone. Id lose them forever. My need to keep everything contained, to keep everything private, was primal.

In my grief, I shut out even my close family and friends. But one thing I did open myself up to was books. Reading other peoples accounts of loss made me feel less alone, more connected. I could read from the safety of my room, where I could cry without fear that someone would hear or see or want to intervene. I underlined passages that spoke to me, then returned to them months and years later, only to find they spoke to me in a whole new way. The authors of these books, I realized, hadnt lost their stories by sharing them. If anything, theyd made them stronger by committing them to paper.

I understood what prompted them to write. I wrote, too, from the earliest stages of my grief. Most of it was stream of consciousness; nothing was crafted or polished, but getting the words down on the page allowed me a small measure of release. Unlike support groups, or even therapy, reading is personal, and so is writing. The combination was exactly what I needed then.

With time, I was able to go out into the world and connect with people again. I met veterans, widows and widowers, and people who had survived personal struggleswhether a death, an illness, or a divorcewho felt a connection with my story. I started to talk about my experiences after Pat died, and I found that other people took comfort in hearing what Id been through. And it was healing for me, tooboth to share finally and to know my story was helping someone else.

So though the person I was in 2004 would never believe shed write a book, thats exactly who Im writing for. Im writing so that someone might open this up in the privacy of his or her room, start to read, and feel a little more connected.

It was good to be in Seattleto hear the foghorns on the Sound, and the deep bellow of the departing steamers; to feel the creeping fog all around you, the fog that softens things and makes a velvet trance out of nighttime.

Ernie Pyle

I leaned back in my office chair, staring at the account board and talking to my coworker Jessica about the days business. We worked together at a consulting firm in downtown Seattle. At the end of every day, Jess and I would catch up and compare notes about clients and current projects. I liked her. She had a quick wit and a foul mouthnot to mention two perfectly placed tattoos: the first, about the size of a quarter, a series of concentric circles on the inside of her left wrist; the second, a row of alien-like dots that crawled up her spine, just high enough to peek out from behind a dress shirt collar. Jess was edgy but lighthearted, and made working in a somewhat uptight corporate office more enjoyable. After almost a year of working together, we had become close friends.

We sat there contemplating the idea of getting a drink downstairs to wait out the rush hour traffic, as we had done many nights before. Jesss drink of choice, Corona, no fruit; mine, a glass of red wine. The receptionist Ted suddenly leaned into my workspace. He looked at me and then let his eyes fall to the ground. Its an image Ill never forgetthat pause as he looked for words.

Um, Marie? he said. There are some people here to see you in the conference roomup front.

I didnt ask him who they were. I somehow knew. Ted was a big teddy bear of a guy who served as our gatekeeper, screening calls, protecting us. But this time I wanted to protect him. I didnt want him to have to tell me; I wanted to spare him. Or maybe I was trying to spare myself, give myself a few more moments before the inevitable. There was something in his voice and body language, or something waiting in the fear that is with you constantly when your loved one is in a war zone.

A chaplain and three soldiers in full dress Army uniforms were standing in the conference room when I entered. They did not have to say a word. I knew instantly that Pat had been killed. They had prepared us for this at the Family Readiness meeting a few months back. Class A dress uniformkilled. BDU, or battle dress uniforminjured. My mind registered their appearance.