Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

s

The

Day

War

Broke

Out

Jacky Hyams is a freelance journalist, editor, columnist and author with over twenty-five years experience in writing for mass-market magazines and newspapers in the UK and Australia.

A Londoner who has spent many years travelling, her feature-writing career was launched in Sydney, Australia, where she wrote extensively for the Sydney Morning Herald, Sun Herald, Cosmopolitan, Rolling Stone, Good Housekeeping, New Idea, Clio and The Australian Womens Weekly. Returning to London, she spent several years as a womens magazine editor on Bella Magazine, followed by six years as a weekly columnist on the London Evening Standard.

Her memoir, Bombsites & Lollipops: My 1950s East End Childhood, and its follow-up, White Boots & Miniskirts: A True Story of Life in the Swinging Sixties, were published in 2011 and 2013 respectively, both by John Blake Publishing. She is also the author of The Real Downton Abbey, a brief guide to the Edwardian era (John Blake Publishing, 2011) and The Female Few, a study of the women Spitfire pilots of the Air Transport Auxiliary, while her most recent books are Bomb Girls: Britains Secret Army: The Munitions Women of World War II and Frances Kray: The Tragic Bride (both John Blake Publishing, 2013 and 2014).

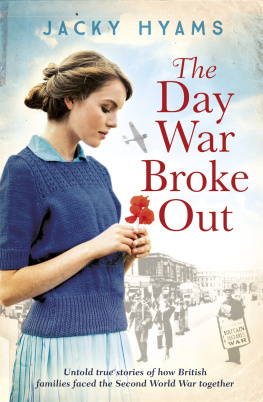

JACKY HYAMS

The

Day

War

Broke

Out

Untold true stories

of how British families faced the

Second World War together

Published by John Blake Publishing,

The Plaza,

535 Kings Road,

Chelsea Harbour,

London SW10 0SZ

www.facebook.com/johnblakebooks

twitter.com/jblakebooks

First published in paperback in 2019

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78946-126-8

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-78946-146-6

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Design by www.envydesign.co.uk

Text copyright Jacky Hyams 2019

The right of Jacky Hyams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright-holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them.

John Blake Publishing is an imprint of Bonnier Books UK

CONTENTS

WARMEST THANKS TO THE EVER-HELPFUL STAFF AT THE JUBILEE Library, Brighton, Hove Library, the research teams at The Keep Archives in Falmer, and in London the Imperial War Museum and Westminster Reference Library.

Many thanks too for the valuable assistance given by Chris McCooey, Lyn Hall, Eva Merrill, Frank Mee, Arian, Ariette and Christian Everett, Katie Avagh and family, Irene Watts, Liverpool Museums, Derby Evening Telegraph (now the Derby Telegraph) and the Mass Observation Archive.

Maureen Hone, Vera Barber, Christine Haig, Jean Ledger, Eileen Weston, Philip Gunyon, Pat Thorne, John Blake of the Barking and District Historical Society, and Selma Montford also gave valuable assistance. Others whose collaboration was greatly appreciated include Pat Cryer (of the website www.1900s.org.uk), Pat Thorne, Alexandra Wilde, Simon Stabler of Best of British/Yesterday Remembered and Dr Kath Smith of Remembering the Past, Tyneside.

Before 1971 the pound was divided into 20 shillings (s).

One shilling was made up of 12 pennies (d).

A pound was made up of 240 pennies.

A guinea was worth 21 shillings, or 1 pound and 1 shilling (1 1s 0d).

I have given prices and sums of money in the original pre-decimal currency, which was replaced in February 1971.

In order to calculate todays value of any original price quoted, the National Archives has a very useful website with a currency converter.: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter. As a general rule of thumb, 1 in 1939 was worth about 40 in todays currency.

HOW DID THE NATION REACT TO THE NEWS THAT WAR HAD just been declared? How did ordinary families across Britain, many still living with the haunting consequences of the previous world war, deal with the arrival of such a devastating pronouncement?

There are times when it may seem that every aspect, military or otherwise, of the events of the Second World War has been explored, examined and revisited time and time again in every medium you care to think of. Each year on Remembrance Sunday the country takes time out to revisit it all to honour the contribution of British and Commonwealth men and women, military and civilian, in the two world wars and the role they continue to play in conflicts across the globe. It is perhaps the one unifying point in any year when due homage is paid to victory and loss, to powerful memory and the significance of the countrys history and, in the First and Second World Wars, to how millions from countries across the world had joined with Britain to fight. Yet for me, one question above all has long dominated my thoughts when we stop to look back each year. Who were we, as a nation, on the day war broke out, 3 September 1939?

What was day-to-day life like for the civilian population of Britain, a country whose very empire at the time spanned an incredible 25 per cent of the globe, yet was still a small island where divisions of class and geography dominated almost everything? There is much to discover about Britain in 1939. In the first instance, the 1930s have mostly been viewed by history in a negative light, dominated as those years were by a global Depression and high unemployment in many parts of the country. To say that ordinary working people then did not have very much in terms of spending power, possessions or all the other accoutrements of the consumer society we now inhabit is not an exaggeration. By todays standards families were, mostly, quite poor. There was very little welfare from an unsympathetic state to prop them up. No NHS either. If you had a job, even if it was poorly paid, you were all right. You might be on the edge, but youd survive. Just.

Families in the 1930s did not experience the same kind of mobility we take for granted either. There was a public transport network and there were, by todays standards, small numbers of cars and motorbikes on the road. But you needed to be quite well-to-do even to own a car. Jumping on a plane? Again, unknown to ordinary people, strictly for the very well-heeled. Yet what is fascinating about the era is that the very beginnings of a consumer society, similar to that of today, had started to emerge in Britain a few years before 1939.

Home ownership, especially in the city suburbs, had started to become a reality for some. Council-house building and the planned demolition of many slum areas by local authorities was under way. The extreme popularity of Hollywood movies had started to exert its powerful influence on millions, especially young women who could copy the fashions and hairstyles of the movie stars of the day, often sitting at home making their own versions of what theyd seen on the big screen. Television, of course, was barely in its infancy. So the huge popularity of cinema held sway even through the war years and the bombing raids. Tickets to a movie palace were, after all, affordable for everyone, even children. From 1937 to 1940 a standard ticket cost just 10d (slightly over 4p).