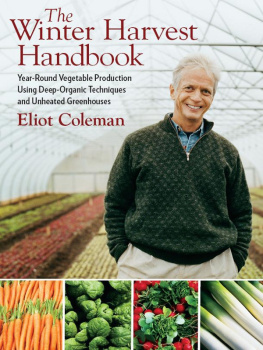

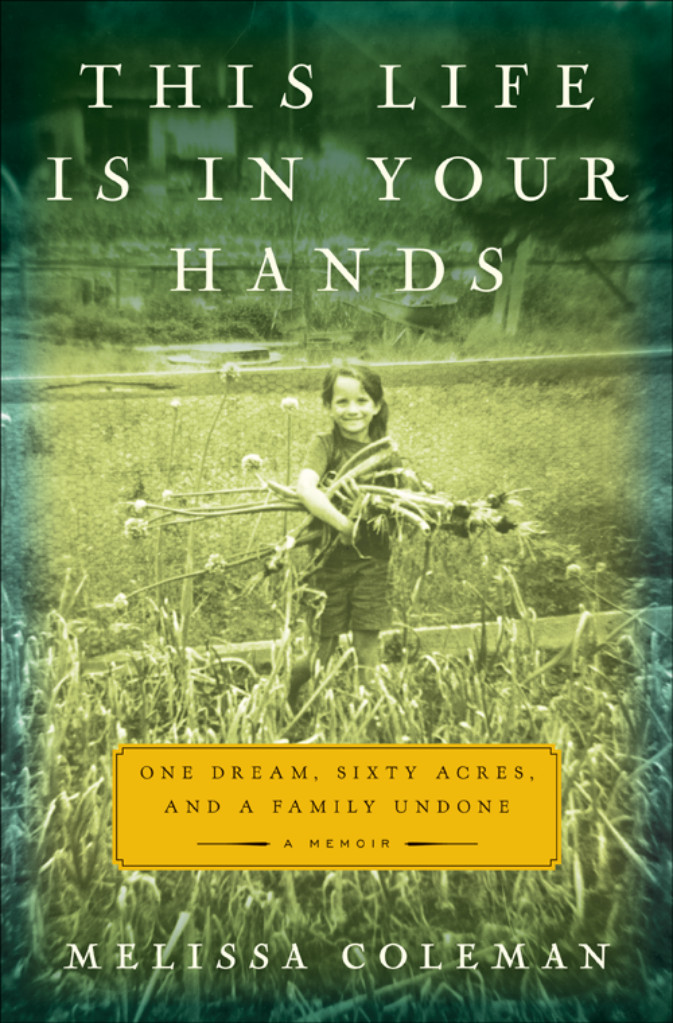

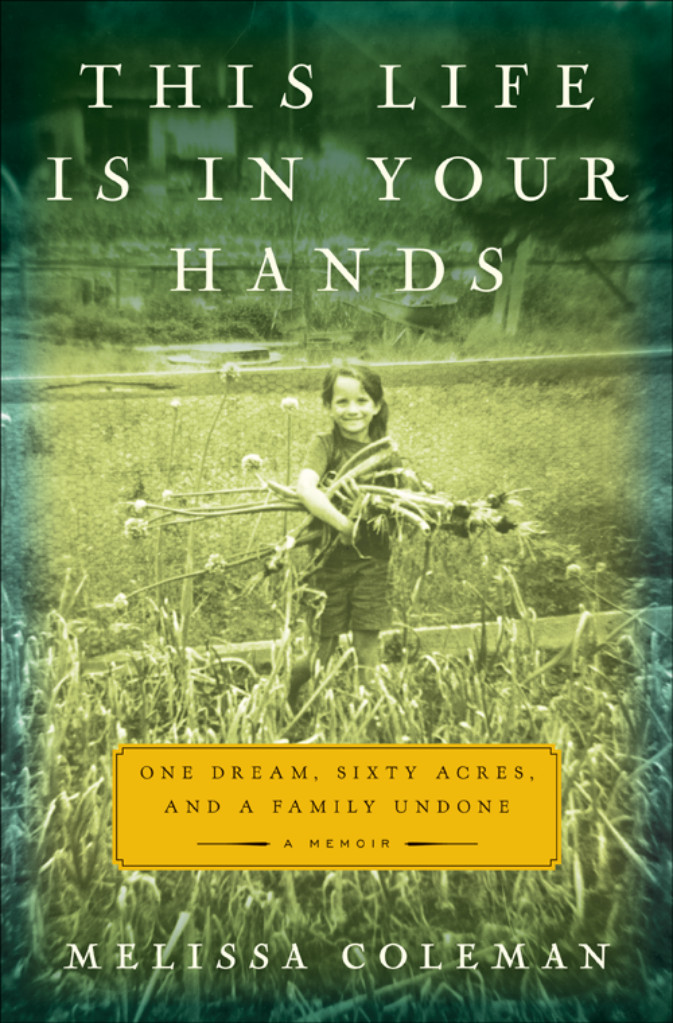

This Life Is in Your Hands

One Dream, Sixty Acres, and a Family Undone

Melissa Coleman

For my sister Heidi

but beauty is more now than dyings when

e. e. cummings

Contents

Family

Livelihood

Sustenance

Seclusion

Companions

Water

Tribe

Paradise

Bicentennial

Loss

Atonement

Mercy

View of Nearings Cove (Photograph by Ian Coleman.)

W e must have asked our neighbor Helen to read our hands that day. Her own hands were the color of onion skins, darkened with liver spots, and ever in motion. Writing, digging, picking, chopping. Opening kitchen cabinets painted with Dutch children in bright embroidered dresses and pointed shoes. Taking out wooden bowls and handing them to my mother, Sue, to put on the patio for lunch. As Mama whooshed out the screen door with hair flowing and child-on-back, the kitchen breathed chopped parsley and vegetable soup simmering on the stove, and the light glowed through the kitchen windows onto the crooked pine floors of the old farmhouse where I stood waiting.

It was a charmed summer, that summer of 1975, even more so because we didnt know how peaceful it was in comparison to the one that would follow.

Ring the lunch bell for Scott-o, Helen called out the window to Mama. She liked to add an o to everyones name. Eli-o, Suz-o, kiddos for the kids, Puss-o the cat. We were the closest she had to children.

As the bell chimed, Helen took my small hand and turned it upward in hers. The kitchen was warm, but her skin cool and leathery. Mama returned with Heidi as I stood long-hair-braided and six-years-brave, holding my breath. We knew about Helen that when she didnt have something interesting to say, shed change the subject. She smoothed my palm with her thumbs and looked down but also in, her cropped granite hair holding the dusty smell of old books.

Tsch, whats this? she asked of the marks Id made with Papas red magic marker.

A map, I told her, proud of the artistry on my fingers. A map of our farm.

Pshaw. She tossed my hand aside like an old turnip from the root cellar.

So she read Heidis palm instead. Heidi was a blue-eyed two-year-old, an uncontainable spirit, everyone said. Even she held still, mouth open, breathing heavy, snug in the sling on Mamas back as Helen smoothed out her little fingers.

Short life line, Helen muttered, bending toward the light from the window, then paused as if catching herself too late.

What do you mean by short? Mama asked, brown eyes alert, mother-bird-like. Thirty, forty years?

Oh, it doesnt mean a thing, Helen said, and began to mutter about the overabundance of tomatoes in the garden.

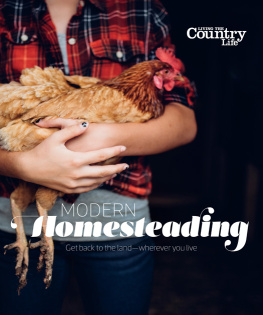

S even years earlier Helen had thought differently, perhaps, as she read my father, Eliots, hands when he and Mama visited, looking for land. Some say hands hold the map of our lives; that the lines of the palm correspond with the heart, head, and soul to create a story unique to each of us. Understanding the lines is an attempt to understand why things happen as they do. Also a quick way to figure out who might make a good neighbor. Helen and Scott Nearing, authors of the homesteading bible Living the Good Life , wanted young people around who would find the same joys in country living as they did. Their philosophy held the promise of a simple life, far removed from the troubles of the modern world. The good life.

Very strong lines, Helen told Papa that summer of 1968. He had the deepest fate line shed ever seen, and wide, capable hands. With hands like his, they could do anything. And such a nice-looking couple, too, young and clean-cutPapa with his sandy tousle of hair, blue eyes, and straight nose, Mamas long, dark hair parted in the middle and kindly chestnut eyes. Shortly after that visit, my parents received a postcard from Helen and Scott offering to sell the sixty acres next door. Thats how we came to be back-to-the-landers, living on a farm cut from the woods without electricity, running water, or phone on that remote peninsula along the coast of Maine. Trying something different to see if truth could be found in it.

T he Vegetable Garden, the sign at the end of our drive said, Organically Grown, with the vegetables in season listed beneath: carrots, lettuce, tomatoes, zucchini. Past a gravel parking lot, the driveway thinned to a grassy lane curving around the orchard and down a gentle slope to a wood-timbered stand with wet-pebble shelves full of fresh produce for sale. Customers and farmworkers came and went as the surrounding gardens ripened beneath the pale disk of midday sun and cicadas thrummed regular as your pulse. On the rise by an overarching ash tree sat our small house, its slanted roof and front eyes of windows looking across the greenhouse and gardens below. The only home Id ever known.

Heidi and I were always outside, naked and barefoot, dancing on the blanket of apple blossoms, skipping along wooded paths, catching frogs at the pond, eating strawberries and peas from the vine, and running from the black twist of garter snakes in the grass. We lay in the shade under the ash tree, gazing up at the crown of leaves and listening to the sounds of the farmbirds calling, goats bleating, chattering of customers at the farm stand, and whispers of tree talk.

When you focused on the leaves fluttering in the dappled light, they vibrated and shimmered into one, becoming a million tiny particles. You felt a shift inside, and you began to vibrate too, on the same frequency as everything else. All secrets were there, all truths, all knowledge. You had to scan with your heart to find what you were seeking. It might not be spoken in words, it might be hidden in rhyme, in song, in images. You knew the tree and the earth were the same as you, made of particles, like you, come together in a different form. You loved it all as you loved yourself.

T here are reasons why nothing lasts forever.

Papa says it was the little red boat Heidi must have carried down to the pond and set afloat. One of our farm apprentices said she was the kind of child who wasnt afraid of anything. Another thought it was the black crow that hung around the farm that spring, a single crow being an omen of death in the family. Someone else suggested it was her lost caul, the rare birth sac myths say will protect against drowning. Others blamed it on our lifestylenot a proper way to raise children.

Mama usually says it was the rain. She didnt worry about us girls playing by the pond because it wasnt that deep during the dry months of summer. But when it rained, the pond filled and turned black as the water caught in barrels under the eaves.

None of these things alone tells the whole story. Only in looking back can you see a pattern in the threads of life, interwoven with the events that would tear them asunder, and within that pattern lies the knowledge Im seekingthe secret of how to live.

Family

Eliot with goat kid and Sue with Lissie, a few days after birth (Photograph courtesy of the author.)

F or the first nine years of my life, Greenwood Farm was my little house in the big woods, located as long ago and far away up the coast of Maine as it was from mainstream America. Five hours from Boston, three from Portland, along winding roads that became successively narrower from Belfast to Bucksport to Penobscot, until they finally turned to dirt. If you were a bird, you could shorten the trip at Camden by cutting over the scatterings of fir-pointed islands on Penobscot BayNorth Haven, Butter Island, Great Spruce Head, Deer Isle. Viewed from above, the islands formed bright constellations in the dark sky of water, a mirror of the universe leading you back in time.

Next page