PRAISE FOR PARALLEL LINES

Something of a genius with the readability of a classic Alan Sillitoe

A remarkable addition to the literature of the Holocaust Sunday Times

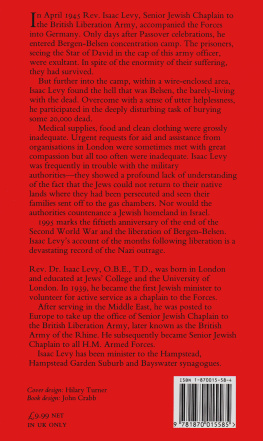

Lantos follows clues, detecting and retracing the steps of his past. He finds a woman who slept in the bunk next to him and his mother in the barracks in Bergen-Belsen, as well as a British medical student who came to help after liberation, and one of the US soldiers whom he met in 1945. Reminds us that the end of the war was by no means the end of the hardship, entailing further resilience. I defy anyone to read this account without retrospective anger on behalf of those who suffered Michelene Wandor, Jewish Chronicle

Anyone who thinks they have read all there is to be said about the Holocaust should read one more book, Parallel Lines. A childs clear-eyed journey to hell paralleled by an adults scientific quest to understand that journey Anne Sebba, author of The Exiled Collector

I have read few autobiographies more extraordinary astonishing Observer

This wonderful memoir introduces a narrator with rare gifts The Tablet

Parallel Lines is for readers who are interested in history and the Second World War and for those who want that the evil befallen on the Jews of Hungary is not repeated ever again Veronika R. Hahn, Npszabadsg, Budapest

A movingly narrated memoir Clare Colvin, Independent

Deeply moving The Age, Melbourne

A classic. I preferred it to Primo Levis If This Is a Man. One of the things I found appealing was his restraint and reserve Edward Wilson, author of A River in May and The Midnight Swimmer

A remarkable historical account and autobiography [which] chronicles the odyssey of Hungarian Jews in 194445, as they were progressively disenfranchised from the national life of Hungary, culminating in the seizure of their homes, property and livelihoods before sending them on trains to places like Auschwitz for extermination, or, in Peter Lantoss case, to Bergen-Belsen Michael N. Hart, Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology

We can now celebrate Peter Lantoss book, which accomplishes something rare: an emotionally moving and, at the same time, clinically precise account NU, Vienna

A childs perspective on the Holocaust a remarkable book. Read it and think about other people elsewhere in the world today who are being persecuted Professor Philip Hasleton, Bulletin of The Royal College of Pathologists

What sets the book apart, and makes this account so refreshing and, oddly, inspiring, is its simplicity. The horrendous events of the last year of the war are invoked with a childs idiosyncratic susceptibility to detail (Lantos was only five years old at the time) the noises, the smells, the human proximity and lack of sentimentality, even when recalling relatives who perished Where, Budapest

Gripping an unembellished account from a child demonstrating youthful resilience. Read this book and be gripped by the drama of Peter Lantos early life Roy O. Weller, Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology

C ONTENTS

mymind,stilllostin flight,oncemore turnedbacktoseethepassagethathadneverletanyoneescapealivebefore.

Dante Alighieri: Inferno

(translated by Michael Palma)

On 19th March 1944, the German Wehrmacht marched into Hungary. Anti-Jewish legislation had been in place since 38, radically restricting Jewish participation in the professions and the civil service, and forbidding mixed marriage. Hungary effectively became a Nazi puppet state and, for five-year-old Peter Lantos and his family, things got much worse.

He didnt understand why his mother was sewing ill-fitting yellow stars on everyones clothes. It made no sense that they had to leave their comfortable home to crowd into a dirty and inhospitable part of their small town. Why was there never enough food now and less pleasure? His commanding grandmother and aunts had shrunk from their former elegance to sorry states. When the news came that they were soon to get onto a train and leave, he was thrilled.

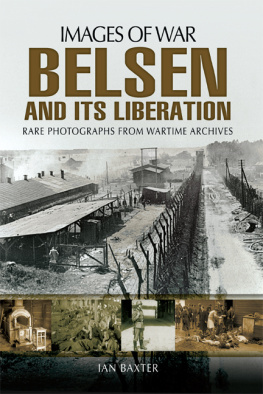

But the train was not as he imagined, and their first stop in the larger town of Szeged, an operational centre for the collection and deportation of Jews, marked a further point on a descent into the abyss. That abyss came via Strasshof and five months in an Austrian work camp near Vienna, where the allied bombs fell with deafening regularity in Bergen-Belsen, the Nazi holding, then concentration camp in northwest Germany, where Anne Frank met her death.

The cold, the stench, the fear, the lice, the epidemic deaths all these form part of Peter Lantoss extraordinary memoir. Here, a childs singular and vivid recollections are amplified by an ageing mans search for the missing links of his past.

Peter Lantos begins his story with a recurring dream. In it, he is looking for the house in which he was born. He cannot find it. He searches amidst familiar streets, goes back to the station, tries another direction, and gets lost again and again. Defeated, he gives up. Only then does he discover that he is in the right place. It is the house that has disappeared.

Lantos is one of the lucky ones. His home may have gone, but, unlike several in his family who ended up in Auschwitz, he lived to tell the tale. He and his mother, though not his father, made it through Belsen. Having returned to post-war Hungary, he also made it through the dark age of Stalinism, where being a Jew was hardly a social advantage. The family timber yard, first expropriated by the Fascists in 1944, was then expropriated once more by the Communists.

By the time of the 1956 uprising, Lantos was in his penultimate year at senior school. His entry into medical school was at first prevented by the fact that he had been labelled a class alien. But his fearless mother saved the day. Ten years later, he won a research fellowship in London. He didnt return to Hungary for many years, one reason being that he had been tried in absentia and sentenced to 16 months imprisonment. Home was now once more lost.

In London, Lantos rose in the medical ranks of neurological research, attaining the prestigious Chair of Neuropathology at the Maudsley Hospital in 1979. His outstanding work contributed to the understanding of Alzheimers and other neuro-degenerative diseases. Though he had revisited Belsen before during an earlier academic visit to Germany, it was only after 1989 and the end of the Soviet era, that his Parallel Lines begin to take shape. Its journey is a riveting one.

When I wrote my novel The Memory Man, I had no idea that Peter Lantos existed. Perhaps I dreamt him, since my Austrian hero, like him, is a neuroscientist who works on memory, only to return in older age to those war-time experiences he has long put aside, to confront their dark matter. The novel arose because the story I told in Losing the Dead of my parents war and its haunting aftermath held an emotional residue that wouldnt leave me alone.

I read Peter Lantoss Parallel Lines some years later. I was struck by the spare quality of a narrative that holds so much remarkable life. I couldnt put it down. We sometimes think there can be nothing left to say about the deadliest moments in the twentieth centurys history, but Lantoss story is unique. Each memoir of the holocaust adds the particularity of a lived experience, arresting in its detail and in the ways in which its author metabolises the past.

It is good that Arcadia has brought back this fine book for our attention.