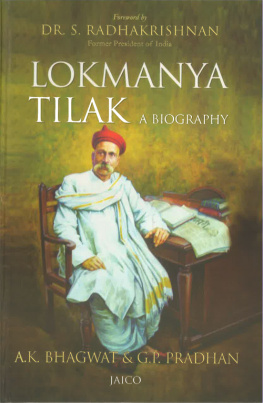

LOKMANYA

TILAK

THE FIRST NATIONAL LEADER

Gayatri Pagdi

CONTENTS

Writing about Lokmanya Tilak is at once a humbling and an exalting experience. Humbling because there has been much written about him in several languages over a period of years. Some of it has been absolutely brilliant, also much in depth, and one wonders if one can, in any way, contribute significantly to what is already present. It is also exalting simply because it presents an auspicious opportunity to explore the life of a man who drew the sword and struck the first significantly hard blow in his countrys valorous fight for independence, the fruits of which we reap today. Like a favourite tale, it continues to engage us no matter how many times we have heard it. Like the national anthem, it fills us with pride every single time we listen to it.

The first national leader who transcended provinces, communities, and languages to establish himself in the hearts of millions, Balwantrao Gangadhar Tilak, Gandhis predecessor, remained a man of the people. He was not a saint whom one would eventually deify but a warrior-hero and a scholar-philosopher; he was very real and therefore that much closer to us, with a powerful and perfect identity that many probably desired to have in those days. He was a man who lived a life of action with total selflessness and withstood all the sufferings in the course of it. His pursuit of the cause of his land, his duty-sans-desire that performed the function of sustaining the society, saw him as a sthithapradnya , a soul steady-in-reason. As he stood, rock-solid and consistent amidst the ocean of turmoil, waves of public emotions arose to meet him. Identified throughout by the term of peoples love and esteem for him, Lokmanya was the admired one.

Tilaks life touched millions. Many came into his life as his students, colleagues, followers, fellow patriots, readers, oppressors, opponents, and admirers. Like a crystal prism, when held up to sunlight, his personality displayed a whole spectrum of colours. He seemed different to different people. Whether it was bouquets or brickbats, prejudice or grudging admiration for this extraordinary man, all of it seemed to come to him with equal force. Whatever emotions he aroused, it was impossible to ignore him. Through the words written on him and the descriptions of his interaction with many in the course of his political, social, educational, and philosophical activity, a lot is revealed about what Lokmanya Tilak meant to the lives of people. This work is a small attempt at exploring Tilaks life through the eyes of the people. It is about the man of the people and the people of his times.

It would not be presumptuous to think that a lot is known of his life already. However, for the sake of ease when we later explore the different facets of his life vis a vis different sections of people, it would help if we followed an outline of his life course.

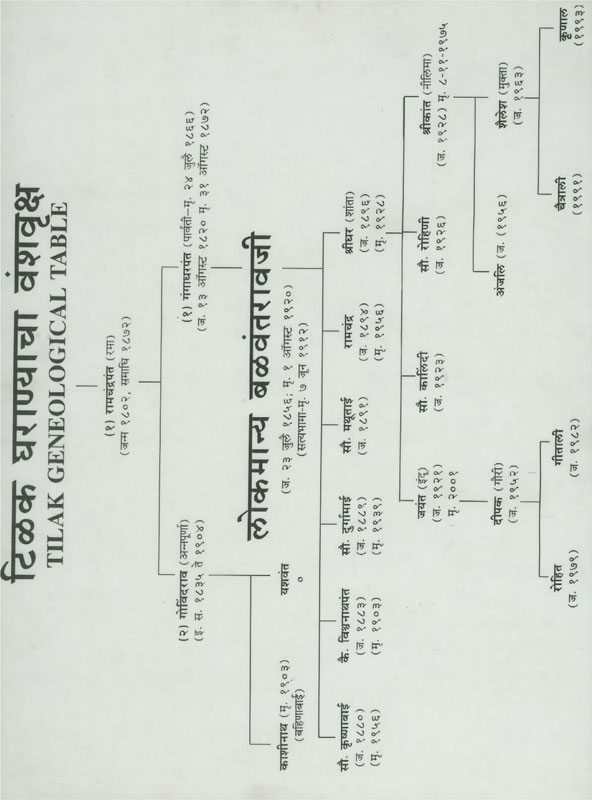

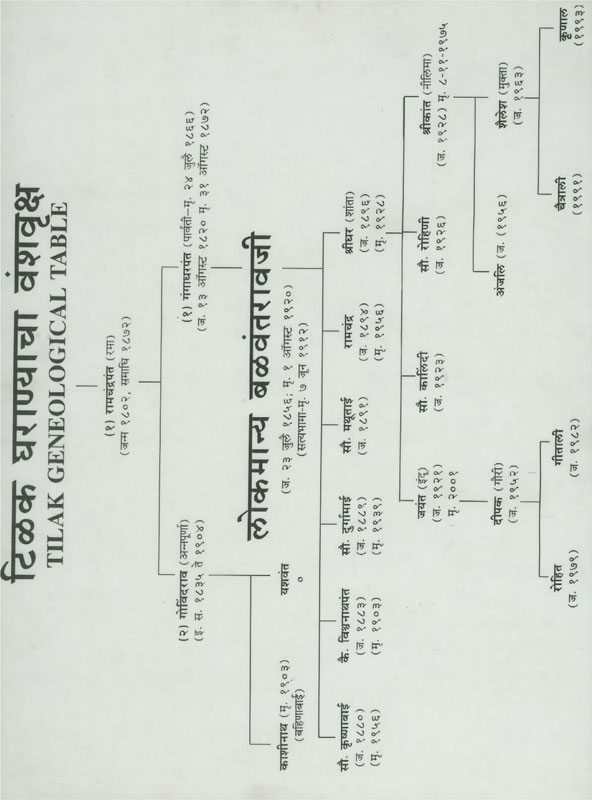

Lokmanya Tilak was born in Ratnagiri on 23 July 1856. His father, Gangadhar Ramchandra Tilak, was a man of academic mind with a respect for knowledge and learning. Earlier an assistant teacher in Ratnagiri, he then became the deputy educational inspector in Thane and Pune. Lokmanya inherited from his father a love for teaching and a mathematical genius. At ease with languages and Sanskrit poetry as also with complex mathematical problems, young Tilak was a student noticed for his brilliance. Tilaks father, conscientious and sincere in his work, fell ill when he insisted on completing the inspection of a hundred schools while his health was already not at its best. By 1872, he was bedridden. His wife had already passed on and he could foresee that he didnt have much time left. He wanted his son to have someone to call his own. According to the tradition then prevalent, Tilak was of a marriageable age. In 1872, Tilak was married to Tapi, who belonged to the very respected Bal family of the Dapoli district in Konkan. She was a healthy girl of nine; the groom was all of sixteen. After marriage, Tapi was renamed as Satyabhama.

The bride and the groom being still very young, Tilak was often said to receive gifts like spinning tops, balls, viti-dandu (tip-cat) sets, chess board sets, pens, and pen stands from his in-laws. His father, in turn, sent the child-bride gifts of numerous dolls and toy kitchen sets. Once Tilak insisted that he did not wish to have toys anymore. He would rather have books. He had no particular interest in the toys and realised how useless they were to him. But more than that was the incessant thirst for knowledge which could only be satisfied through books. Needless to say, his wish was fulfilled.

His fathers condition deteriorated further and things now looked bleak. Tilak later wrote in the introduction to the GeetaRahasya that as a son who was around his ill father, he was asked to read out the Prakrit critique of the Bhagvad Geeta called Bhashavivruti to his father every day.

The father, ever so careful regarding the future of his son, had made financial arrangements for him to be able to complete his education without trouble. He wanted his son to complete his graduation and hoped that he would do so with the help of a scholarship. However, in case that was not possible, he had left five thousand rupees for Tilak for his education to go on smoothly.

After Tilaks father passed away he was looked after by his uncle and aunt, both of whom loved him like their own son. In the absence of his father, Tilak, though a part of a warm family, grew more and more emotionally independent.

After passing the entrance examination, Tilak joined the Deccan College in Pune. For the first six months he walked to the college daily. He also had to cross a river on the way and a boat ride with his friends was a part of his commuting. As a boy he wasnt well built. Later, Tilaks eldest son-in-law, Vishwanath Gangadhar Ketkar, revealed that often Tilaks friends teased him because he looked very slight in comparison to his wife. Tilak decided to do something about it and spent an entire year concentrating on building a good body at the cost of his studies. He soon became an expert in wrestling, malkhamb , and other traditional athletic sports. He was also fond of swimming and swam every time he got an opportunity to. He found rowing of boats interesting and was good at it. However, he had no interest in cricket or tennis. He believed that it was a snobbish way of digesting your food in the open air, not a real means to have a good body.

The exercises did him good. His diet improved and the man who otherwise ate only a bit of rice and milk was suddenly opting for eight to ten roti s at a time, along with vegetables, pulses, and other healthy food. Soon he was a very strong young man who often wandered bare-chested in his room with just a wrap around himself during the most severe winter. He was never known to suffer from any illness, not even minor ones. He believed firmly that one could sometimes skip studies or other such mental activity but physical exercises were a must every single day.

With an improvement in his physical health, his mind brightened even further and Tilak now attacked his studies with equal aggression. He believed in going down to the root of every topic and understanding it thoroughly instead of allowing himself a superficial understanding which would fetch him good grades. He read a lot, often books outside the curriculum, which helped him understand his studies better. He was also very particular about handling his books carefully and some of his notebooks were found to be in excellent condition even after a quarter of a century.

Next page