Table of Contents

To

Anika and Rohan

for all the joy you have brought into our lives

Lar o Bar, Yaw Afghan

Low (lowlands of Pakistan) or high (highlands of Afghanistan), Afghans are one

Contents

Pull out your swords and slay anyone that says Pashtun and Afghan are not one! Arabs know this and so do Romans: Afghans are Pashtuns, Pashtuns are Afghans.

Khushal Khan Khattak

Asia is but a body of mud and water. Its throbbing heart is the Afghan nation. The Afghan nations relief gives relief to Asia and its corruption corrupts Asia.

Mohd Iqbal

GROWING UP, I KNEW TWO things about the Pashtuns. Both were benign. The larger-than-life Abdul Ghaffar Khan and his deep links with Gandhiji and the non-violent Indian freedom struggle further reinforced the benign image of the Pashtun. Bollywood pitched in too, with the depiction of the Pathan as a friend and someone who fought on the side of the oppressed, especially women, and a host of actors who traced their origins to Pashtun ancestry.

Later, when older, I was, however, stunned by the violence in Afghanistan that was in total contrast to the image I had about the Pashtunsthe Soviet invasion, the Mujahideen, the civil war, the depredations of the Taliban, the 9/11 tragedy, the war on terror and now the Taliban back in power made me want to find out what went wrong with the Pashtuns. Other preoccupations prevented me from writing about them till now.

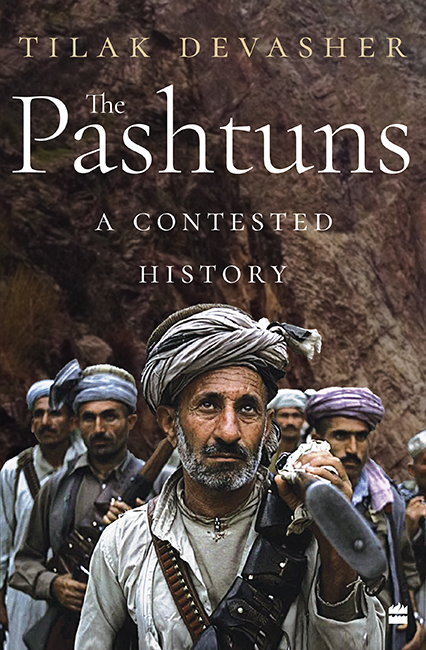

This is a book about the Pashtuns who straddle an area of more than 100,000 square miles. I refer to this land as Pashtunistanthe land of the Pashtuns. This ancient land and its people have been contested between empires and seen many vicissitudes over the centuries. Today, the Pashtuns are divided by the British era Durand Line into Afghanistan and Pakistan. As a result, the Pashtuns, despite being the largest Muslim tribal population in the world, are without a state of their own.

Though divided between two countries, the Pashtuns share a common ideology of descent, common ethnic, cultural, linguistic and familial bonds, common historical memories, and belong largely to the Sunni Hana school of Islam with pockets of Shias. These unifying bonds do justify a book that strives to see the Pashtuns as a single entity inhabiting a single piece of real estate, as it were, distinct from its neighbours. This book is also written in the belief that the present division is just one of the several avatars that this land and its people have been subject to over the centuries. Though no discussion of the people can be divorced from the countries in which they reside, the book is neither in the main about Afghanistan nor Pakistan, but about the Pashtuns.

In the words of Olaf Caroe, one of the notable tragedies amongst the many tragedies of the Pashtuns is:

Although the Pathans have stood for centuries in the corridors between Khurasan and the Indian sub-continent just at the very point where great civilizations have met and contended; although their mountain homes have been swept by conquering armies again and again, to rise like a breakwater from the sea; although the conquerors have passed on to found great empires, yet the Pathans who hold the gate have never been given a vision of their own story in perspective. In the modem sense there is no connected history of the Pathans in their own land, whether written by themselves or by any of those through the ages who passed by.

This book is not a granular study of all the multifaceted dimensions of Pashtun life. Instead, it tries to provide a thumbnail sketch of some salient features that could help in understanding the key trends amongst the Pashtuns and their history. This is important because Pashtuns matter and matter vitally. Such a comprehension, especially of two important forcesPashtun nationalism and Pashtun extremismand their potential combination are critical for peace and stability in the region. Superficial understanding and prescription has had, and could continue to have, devastating consequences for the region. Thus, insecurity and instability in this crossroads would radiate insecurity in the whole region, lead to a surge of refugees seeking safety elsewhere, lead to an increase in drug trafficking and provide space for global terrorists in ungoverned spaces.

A word about nomenclature. There has been a fair amount of confusion about the terms Pashtun, Pakhtun, Pathan and Afghan. The ambiguity stems from the fact that the Pashtuns have been commonly referred to interchangeably with Afghan. According to Nahi Misdaq, the name Afghan was recorded on stones in Behistun and Susa (in Persia) and on the tomb of Darius the Great in Naqsh-e-Rustem in the fth century BC as Abagon. The Persian usage of Abagon, Afghan or Affaghanah was their name for the Pashtuns.

Until the Sikh conquests in the nineteenth century and then the British Raj, the Pashtuns were politically united and part of a Pashtun empire that stretched eastwards as far as the Indus river. The Sikh seizure of the Pashtun lands and the bulk of the population between the Indus and the Khyber Pass, and its formalization by the Durand Line Agreement with the British in 1893, was a devastating blow to the Pashtuns. After having lost a large portion of the Pashtun population, Amir Abdur Rahman expanded his empire northwards, making large non-Pashtun territories part of his empire. Thus, the nomenclature Afghan became a multi-ethnic identity rather than that of a single ethnic group. Till today, in the official documents in Pakistan, such as land papers, court documents, police records, the word Afghan continues to be mentioned after their names, a practice that was started under the British. In the Indian sub-continent, the word commonly used for the Pashtuns was Pathan.

Underlying the confusion, Pakistani Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan asked in the Constituent Assembly in March 1948 when Ghaffar Khan was present: Is Pathan the name of a country or that of a community? Ghaffar Khan clarified: Pathan is the name of the community and we will name the country as Pakhtoonistan. He added, I may also explain that the people of India used to call us Pathans and we are called Afghans by the Persians. Our real name is Pakhtoon. We want Pakhtoonistan and want to see all the Pathans on this side of the Durand Line joined and united together in Pakhtoonistan. Later, in 1975, Ghaffar Khans son, Wali Khan, the National Awami Party leader, was asked to clarify whether he was a Muslim, a Pakistani or a Pashtun first. His famous reply was that he was a six-thousand-year-old Pashtun, a thousand-year-old Muslim and a twenty-seven-year-old Pakistani.

During the British rule, several authors tried to make a distinction between Afghan and Pathan: the Afghans were considered under Persian influence being part of the Safvid Empire of Persia and spoke Darri while the Pashtuns or Pathans had greater interaction with India, especially the Mughal Empire of Delhi, which ruled over them from Peshawar, Kabul or Kandahar. A word about Pakhtun and Pashtun. Tribes in the north of the region use the term Pakhtun while the southern tribes use the term Pashtun. Similarly, Pakhto is used to describe the language in the north and Pashto in the south.

In this book, the term used throughout is Pashtun, which refers to the entire ethnic group and Pashto for the language of the Pashtuns.This book then is about the Pashtuns. This is their story.

I would like to thank my wife for her continuing patience in allowing me to spend days, weeks and months in my study reading, researching and writing this book, and for her abiding faith that I was actually doing something worthwhile! I would also like to thank my son and daughter-in-law and my daughter and son-in-law for their constant support. My thanks also to Riya Sinha, research associate, the Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP) for her help in researching material for the book during the trying COVID times. Finally, I would like to thank Swati Chopra, Executive Editor, and Shreya Lall, Senior Editor, at HarperCollins