The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

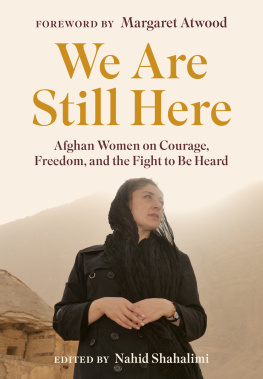

FOR ASMA SAFI

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Poetry magazine and to the Harriet Monroe Poetry Institute. Portions of this book originally appeared, in different form, in Poetry s Landays issue.

I call. Youre stone.

One day youll look and find Im gone.

The teenage poet who uttered this folk poem called herself Rahila Muska. She lived in Helmand, a Taliban stronghold and one of the most restive of Afghanistans thirty-four provinces since the U.S. invasion began on October 7, 2001. Muska, like many young and rural Afghan women, wasnt allowed to leave her home. Fearing that shed be kidnapped or raped by warlords, her father pulled her out of school after the fifth grade. In her community, as in others, educating girls was seen as dishonorable as well as dangerous. Poetry, which she learned at home from women and on the radio, became her only continuing education.

In Afghan culture, poetry is revered, particularly the high literary forms that derive from Persian or Arabic. But the poem above is a folk coupleta landayan oral and often anonymous scrap of song created by and for mostly illiterate people: the more than twenty million Pashtun women who span the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Traditionally, landays are sung aloud, often to the beat of a hand drum, which, along with other kinds of music, was banned by the Taliban from 1996 to 2001, and in some places still is.

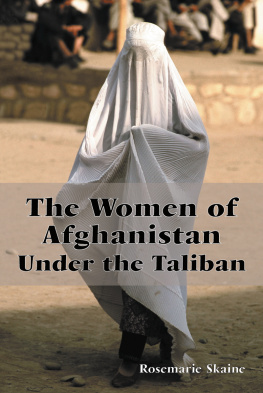

A landay has only a few formal properties. Each has twenty-two syllables: nine in the first line; thirteen in the second. The poem ends with the sound ma or na . Sometimes landays rhyme, but more often not. In Pashto, they lilt internally from word to word in a kind of two-line lullaby that belies the sharpness of their content, which is distinctive not only for its beauty, bawdiness, and wit, but also for its piercing ability to articulate a common truth about love, grief, separation, homeland, and war. Within these five main tropes, the couplets express a collective fury, a lament, an earthy joke, a love of home, a longing for an end to separation, a call to arms, all of which frustrate any facile image of a Pashtun woman as nothing but a mute ghost beneath a blue burqa.

The subjects of landays, from the Aryan caravans that likely brought these poems to Afghanistan thousands of years ago to ongoing U.S. drone strikes, are remixed like rap, with old words swapped for newer, more relevant ones. A womans sleeve in a centuries-old landay today becomes her bra. A colonial British officer becomes a contemporary American soldier. A book becomes a gun. Each biting word change has much to teach about the social satire fueled by resentment that ripples under the surface of a womans life. With the drawdown of American forces in 2014 looming, these are the voices of protest most at risk when the Americans pull out. Although landays reflect fury at the presence of the U.S. military and rage at occupation, among other subjects, many women fear that in the aftermath of Americas presence they will return to lives of isolation and oppression as under the Taliban.

Yet its also true that eight out of ten Afghan women dont live in cities but in rural places where this most recent decade of war hasnt altered public life. Their battles for growing autonomy, especially for young women, take place in the privacy of their homes, as these poems can attest. Consider this one:

You sold me to an old man, father.

May God destroy your home; I was your daughter.

Landays began among nomads and farmers. Shared around a fire, sung after a day in the fields or at a wedding, poems were a popular form of entertainment. These kinds of gatherings are now rare: forty years of chaos and conflict have driven millions of people from their homes. War has also diluted a culture and hastened globalization. Now people share landays virtually via the Internet, Facebook, text messages, and the radio. Its not only the subject matter that makes them risqu. Landays are usually sung, and singing is linked to licentiousness in the Afghan consciousness. Women singers are viewed as prostitutes. Women get around this by singing in secretin front of only close family or, say, a harmless-looking foreign lady writer. Given the nature of secrecy and gossip, it can be easier for a Pashtun woman to answer the intimate questions of a total stranger. Familiarity breeds distrust.

Usually in a village or a family one woman is more skilled than others at singing landays, yet men have no idea who she is. Much of an Afghan womans life involves a cloak-and-dagger dance around honora gap between who she seems to be and who she is.

These days, for women, poetry programs on the radio are one of the few available means of access to the outside world. Such was the case for Rahila Muska, who learned about a womens literary group called Mirman Baheer while listening to the radio. The group meets in the capital of Kabul every Saturday afternoon; it also runs a phone hotline for girls from the provinces, like Muska, to call in and read their work or to talk to fellow poets. Muska, which means smile in Pashto, phoned in so frequently and showed such promise that she became the darling of the literary circle. She alluded to family problems she refused to discuss. So many women, urban and rural, shared similarly dire circumstances that her allusions to doomsday seemed nothing special.

One day in the spring of 2010, Muska phoned her fellow poets from a hospital bed in the southeastern city of Kandahar to say that shed set herself on fire, burned herself in protest. Her brothers had beaten her badly after discovering her writing poems. Poetryespecially love poetryis forbidden to many of Afghanistans women: it implies dishonor and free will. Both are unsavory for women in traditional Afghan culture. Soon after, Muska died.

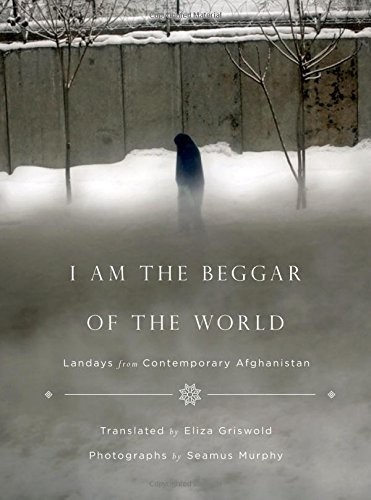

After learning about Muska, I traveled to Afghanistan with the photographer Seamus Murphy on assignment with The New York Times Magazine to piece together what I could of her brief life story. Finding Muskas family seemed an impossible taskone dead teenage poet writing under the safety of a pseudonym in a war zonebut eventually, with the aid of a highly effective Pashtun organization called WADAN, the Welfare Association for the Development of Afghanistan, we were able to locate her village and to find her parents. Her real name, it turned out, was Zarmina, and her story was about far more than poetry.

This was a love story gone wrong. Engaged at an early age to her cousin, shed been forbidden to marry him because after the recent death of his father, he couldnt afford the volver , the bride price. Her love was doomed and her future uncertain; death became the only control she could assert over her life. The one poem to survive her is the landay above, which, like almost all landays, has no author. Although she didnt write this poem, Rahila Muska often recited it over the phone to the women of Mirman Baheer. Of the tens of thousands of landays in circulation, the handful a woman remembers relate to her life. Shes relatively free to utter them because, in principle, she didnt author them. Without anyone noticing, the word or two she alters is woven into the shape of the poem. Unlike Muskas notebooks, this little poem cant be ripped up and destroyed by her father. Landays survive because they belong to no one.