Thanks to Father Victor Vead of the St. Augustine Catholic Church, for permission to reprint the portrait of Augustine Metoyer and the Church of St. Augustine on page 5.

Thanks to Trident Press International, for permission to reprint the image of General Bankss Army crossing Cane River in 1864.

CANE RIVER . Copyright 2001 by Lalita Tademy. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

For information address Warner Books, Inc., Hachette Book Group, 237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017.

A Time Warner Company

ISBN: 978-0-7595-2242-8

A hardcover edition of this book was published in 2001 by Warner Books.

First eBook edition: April 2001

The Warner Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

AUTHORSNOTE

M y great-grandmother Emily died in bed at her Louisiana home at the end of the summer of 1936, with $1,300 in cash hidden under her mattress. Although she passed away twelve years before I was born, her presence is firmly imprinted in our family lore. Neither my mother nor her brothers ever talk about Emily without a respectful catch in their throat, without a lingering note of adoration in their tone.

Ive been told that Great-Grandma Tite (Emilys nickname, rhymed with sweet) was very beautiful, and this is verified by the four photographs I have of her, two of which hang on the wall of my home in California. She was full of life into her seventies, dancing alone in the front room of her Aloha farmhouse on Cornfine Bayou to the music from her old Victrola, high-stepping and whirling to the cheering-on of family gathered on Sunday visiting day. Always, at the end of her performance, she would arch her spine and kick back one leg, little booted foot suspended in air beneath her long dress until the clapping stopped. It was her trademark move. My mother and all of the other surviving grandchildren remember this vividly. Laughter and fun surrounded Grandma Tite, they say, describing the flawless skin, thick chestnut hair, high cheekbones, thin sharp nose, and impossibly narrow waist. My mother has said to me often, each time with a proud, wistful smile, She was an elegant lady, like Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy.

I always found this last statement impossible to embrace. I now know that Emily Fredieu was born a slave in 1861, lived deep in the secluded backcountry of central Louisiana, dipped snuff, and drank homemade wine every day, insisting that all visitors, even children, drink along with her. She bore five children out of wedlock over the thirty-plus-year span of her liaison with my great-grandfather, a Frenchman. Interracial marriage wasnt against the law for all of the time they were together, but it was dangerous and against custom for a colored woman, even if she did look white, and a white man to be together. My great-grandmother Emily was color-struck. She barely tolerated being called colored, and never Negro. My mother, the lightest of the grandchildren, with skin white enough to pass if she chose, was a favorite of hers. It is difficult to reconcile these facts and confirm my mothers judgment of elegant.

I was always unsympathetic to the memory of Emily because of her skin color biases, although I never dared say so to my mother. But at the same time I was envious of Emilys ability to stare down the defeats of her life and aggressively claim joy as her right, in ways I had never learned to do.

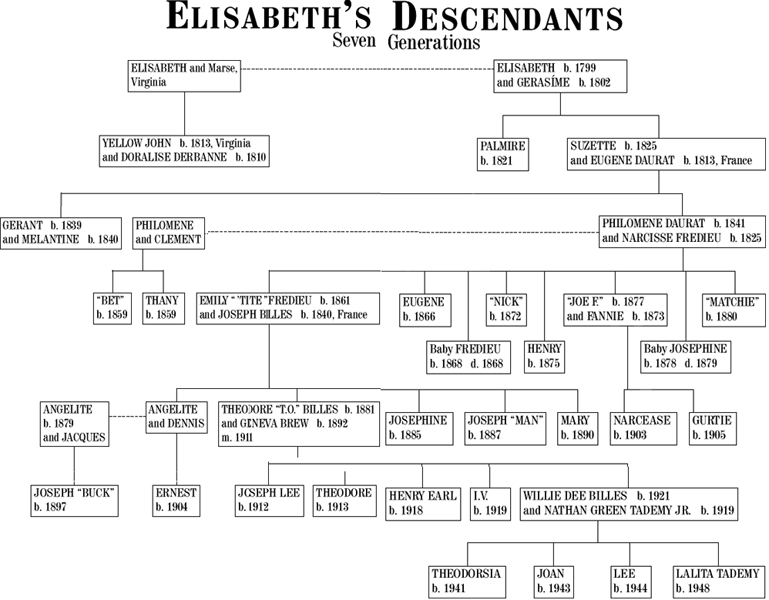

Emily fascinated me for years, an untapped mystery, but my life was too busy to dwell on impractical musings with no identified purpose. I loved my world, jolting awake every morning, impatient to begin the day, savoring the next deal, the next business to build or turn around, the next promotion. For two decades I had hoisted myself upward, hand over hand up the corporate ladder, until I was a vice president for a Fortune 500 high-technology company in Silicon Valley. The position brought all-consuming work, status, long hours, and stock options. But every so often, while reviewing strategic businesses in small, airless rooms, I found myself secretly thinking about Emily, who she was, how she came to be. During budget reviews my mind would drift to Emilys mother, Philomene, about whom I knew so little, only as a name in a brief two-page family history written twenty years before by a great-cousin and sent to me by my uncle. I began to develop a nagging and unmanageable itch to identify Philomenes mother, to find out if she lived on a plantation as someone elses property, a slave, or if she had been free.

In 1995, driven by a hunger that I could not name, I surprised myself and quit my job, walking away from a coveted position for which I had spent my life preparing. Crossing back and forth from California to Louisiana, I interviewed family members and local historians, learning just how tangled the roots of family trees could become.

I scanned documents until headaches drove me from moldy basements where census records or badly preserved old newspapers from the 1800s and early 1900s were stored. In assorted Louisiana courthouses I waded through deeds, wills, inventories, land claims, and trial proceedings. Joining the Natchitoches genealogy society led me to some private collections, including letters. The search for my ancestors moved beyond a pastime and became an obsession.

A series of discoveries challenged what I thought I knew about Louisiana, slavery, race, and class. I thought Creole meant mixed-race people, black and white, but was informed in clipped tones that Creoles were only the white French-speaking descendants of the early French settlers, a snobbish distinction that clearly separated them from the black families the Creole men created on the side, as well as elevating them above their lower-class French-speaking Cajun cousins. I discovered that most plantations were not like the sprawling expanses of Tara in Gone With the Wind but were small, self-contained communities, surrounded by farms that were smaller still. I discovered that the horrifying institution of slavery played out in individual dramas as varied as there were different farms and plantations, masters and slaves.

As I tightened my search for Philomenes mother, the trail led to Cane River, a complex, isolated, close-knit, and hierarchical society whose heyday was in the early 1800s. It was a community that stretched nineteen miles along a river in central Louisiana where Creole French planters, free people of color, and slaves coexisted in convoluted and sometimes nonstereotypical ways. In Cane River the free people of color, or

A Time Warner Company

A Time Warner Company