THE LARGE OLD man in the black turtleneck was asked to raise his hand and swear to God. No, the man replied, I will not swear on God, because I dont believe in the conventional sense and in this nonsense. What I will swear on is my children and my grandchildren.

Unfazed, the judge told the clerk to read another oath. Will you solemnly affirm, the clerk tried again, that the testimony you are about to give will be the whole truth and nothing but the truth

I do indeed, the man interrupted, impatient to get this done.

The courtroom hushed as the man turned and wedged himself onto the witness standno easy task, given that he weighed somewhere above three hundred pounds. Then he was asked to state his name.

Marlon Brando, the man saidadding, half a second later, Junior.

The cameras, as always, were on him.

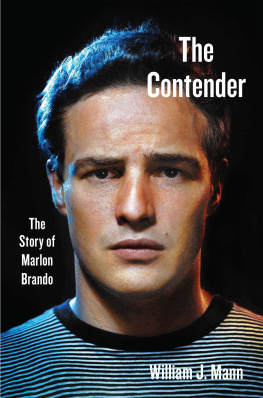

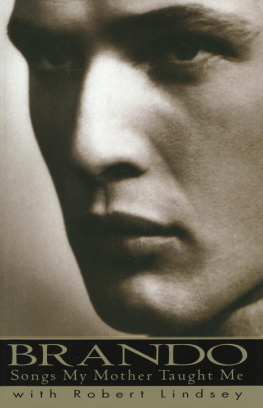

THE STORY OF Marlon Brando Junior does not really begin here, in this sad, wretched courthouse in Santa Monica, California, on February 28, 1991. Brandos story might better be said to have originated in the American Midwest, where he was born, or in New York, where he first rose to prominence. But Brando had been challenging false gods his entire life, refusing to swear by convention and calling out nonsense everywhere he went, from the Hollywood Hills to the South Pacific to the arrondissements of Paris. So, while this moment in Santa Monica, with Brando sitting sideways on the witness stand (the only way he fit), is neither the beginning nor the end of our story, it is one way into it, as the camera draws in close on a sad, broken, yet ever-defiant old man.

Brando was testifying on the third day of a sentencing hearing for his thirty-two-year-old son, Christian, who had pled guilty to voluntary manslaughter. The man whom Christian had shot on the night of May 16, 1990, at his fathers house high above Los Angeles on Mulholland Drive, had been Dag Drollet, the father of his sister Cheyennes baby. Six months pregnant at the time, Cheyenne had told her brother that Drollet beat her. I didnt mean to do it, Christian cried to his father, insisting hed only been trying to scare the young man, that hed thought the guns safety catch was on. Brando tried to revive Drollet with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. But paramedics pronounced Drollet dead.

Christian was initially charged with first-degree murder. For the next ten months, the case was a circus of lawyers and witnesses, one of the first big celebrity murder trials to receive cable news coverage and one of the most publicized criminal cases in Los Angeles history, according to the Los Angeles Times. Cheyenne was revealed to be suffering from schizophrenia; her history of accidents and institutionalizations was bannered in the tabloids. The media coverage made the tragedy a thousand times worse for everyone involved. For years, Brando had railed against such celebrity peephole publicity, as he called it. Now he watched helplessly as his family deteriorated around him. Cheyenne, emotionally fragile, was spirited out of the country, away from prosecutors who wanted to put her on the stand. Back in her native Tahiti, the twenty-year-old woman gave birth to a son, Tuki, then tried to kill herself. Misery has come to my house, Brando said, his voice raspy, his eyes bloodshot, to the reporters who gathered on Mulholland Drive.

Eventually, Christian pled guilty to the lesser charge of manslaughter. Still, his father feared hed get twenty years. On the stand, Brando made one point clear: This is the Marlon Brando case. If the defendant had not been the son of the man widely regarded as the greatest American actor of all time, but black or Mexican or poor, the media wouldnt be in this courtroom.

Black and Mexican and poor lives, Brando charged, mattered little to the media. For most of his career, hed used his fame to draw attention to racism and injustice, decrying the media indifference when young men of color were imprisoned at rates higher than those for white men. Now Brandos celebrity had turned against him. Fame, Brando believed, was an amoral beast, one hed been wrestling with for forty-four years without ever managing to weaken its hold. He hadnt wanted fame, and forever mourned the anonymity once so dear to him. I cant convey how discomforting it is not to be able to be a normal person, Brando once lamented, a statement that goes a long way toward allowing us to understand him.

Brando was never like other celebrities, with their gazes forever outward. He was a thinker, an observer, an examiner of himself and the world, with the goal of figuring out both. For much of his time in the public eye, Brando had served as the nations critic, pointing out societys injustices and failures. Now, trying to convince a judge to show mercy to his son, he was about to reveal some of his own.

I led a wasted life, he said on the stand, a statement that surprised many. For, while Brandos life had often been controversial and contentious, few would have called it wasted. This was the man who had revolutionized acting! Yet Brando was speaking personally, in a regretful tone rarely heard in previous interviews, where hed usually been in control, needling or bamboozling his interviewers. To the court, Brando said hed chased a lot of women and fought bitterly with Christians mother, and failed to shield his son from their hostility. Shifting that enormous body, Brando admitted, Perhaps I failed as a father. There were things I could have done differently.

Things I could have done differently. Back through the years, that statement reverberated. So many things could have been different. Brandos first dream back in Illinois had been to be a drummer. He lived for rhythm, he said, and for a while, hed also considered a career as a dancer. Brando came to despise acting. Many times, he wanted to quit and do something else, something he found more meaningful and fulfilling, such as political activism. He might have been happier if he had done so, more content; he also might have caroused less, committed himself more to his work and his family. But he hadnt. And it was too late to do things over now.

Never a man to indulge the vanity of regret for very long, here on the stand, Brando was, at last, forced to consider it. The pain on his face flashed intermittently, like a neon sign: sometimes visible and unbearable; other times blank and dark. He gripped the railing of the witness stand. I did the best I could, he said. He was crying.

Some in the courtroom were moved by Brandos words. Others hardened against them. He was giving to Christian the one thing he knew how to do best, his acting talent, said his friend George Englund, from whom he was later estranged. But this wasnt the greatest actor of his time seizing everyones imagination. This was a former champion, overweight, out of shape, sloppy with technique.

The family of Dag Drollet, whom Brando addressed next, also thought he was acting. I cannot continue with the hate in your eyes, Brando said, turning to face them. Im sorry with my whole heart. He delivered a long apology in French, their primary language, his tears falling. Yet Drollets father remained unmoved.

Was Brando acting on the stand? He liked to say that everyone acts. We act every single day, he once said, to bring about a certain outcome, to ensure something we care about comes true. So, if he loved his sonand he did, very muchBrando would of course try to give the very best performance he was capable of giving on the stand. Wasnt Dag Drollets father trying to be equally persuasive when he stood to speak, hoping to convince the judge in the opposite direction, to sentence Christian to the harshest term possible? Two different intents, two identical strategies. Acting doesnt mean the emotions arent real; that was always Brandos point. For fifty years, the best Marlon Brando performances were those that layered his own deeply felt experience onto his brilliant imagination. So why was Drollet called true and Brando false?