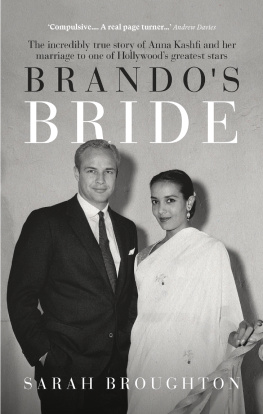

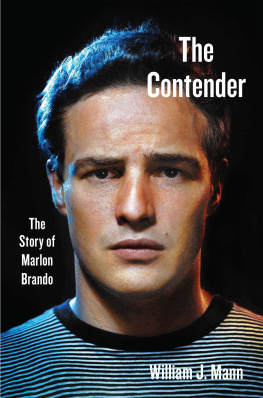

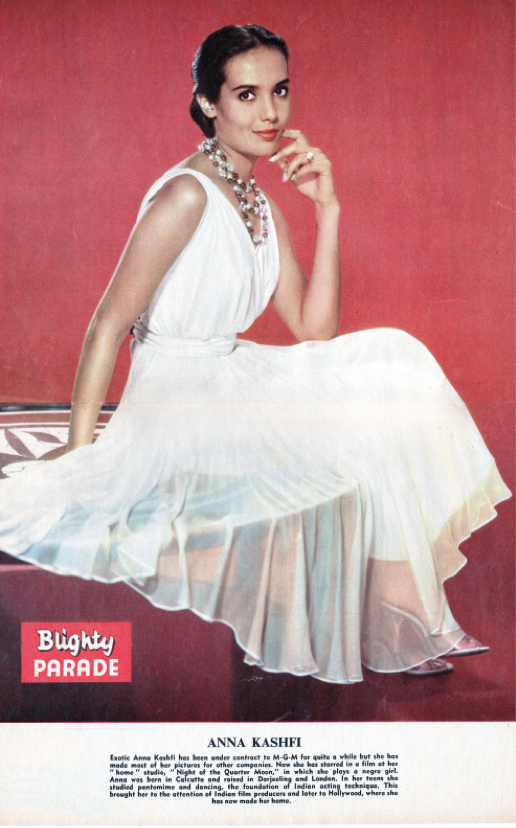

Who Was Brandos Bride?

Some people say my daughter looks Indian, that she is dark-skinned. Well maybe she gets that from my mother. She was French and came from Dijon, in the south.

William OCallaghan

Chicago Daily Tribune , October 19th 1957

RAILWAY PEOPLE, RAILWAY LIVES

Chakradharpur is a railway town at least since the 1890s when the first seventy-two miles of track connecting it with the Bengal Nagpur Railway were laid. Located in Eastern India in the heart of the Chota Nagpur Plateau, it was a quiet place surrounded by mountains and lush green jungle with the Sanjay River running through its eastern fringes. It was a peaceful town of mixed cultures where all four of the major religions Christianity, Islam, Sikhism and Hinduism co-existed. In the 1920s it was home to supporters of Indian Independence, Gandhi, and the Khilifat Movement against the British. A decade later it was where William and Phoebe OCallaghan were living when their daughter Joan was born.

The railways were an important source of both employment and status for Anglo-Indians. The British treated them as a buffer community; they spoke English as well as the local language, they could get the job done and they helped seal the relationship between British and Indian workers. Mindful that the railways were a symbol of imperial power and therefore could be sabotaged, a space was created for the Anglo-Indians to keep the racial politics vis--vis Indians intact. The railways were not the only area where the British depended on the Anglo-Indians. According to Anglo-Indian historian Beverley Pearson, without their support British rule would have collapsed:

We ran the railways, post and telegraph, police and customs, education, export and import, shipping, tea, coffee and tobacco plantations, the coal and gold fields If it had any value the British made sure we ran it.

Railway towns, like Chakradharpur tended to be divided into three distinct communities: the Railway Lines, the cantonments, and the city. The cantonments were where the British lived originally military bases which during the 19 th century were developed into fully fledged small towns of their own with parks, shops, churches and schools. According to John Masters in Bhowani Junction , his novel about an Anglo-Indian community in pre-Independence India, the city was where God knows how many thousand Indians are packed in like sardines. Railway people, like the OCallaghans, lived and worked in a part of town known as the Railway Lines (also called Railway Colonies), an area built to accommodate employees and their families. This was where a particular kind of British culture and social position predicated on notions of race, caste and hierarchy was preserved.

Indian railway mania had been under way since the 1840s when the then Governor-General of India, Lord Hardinge, allowed private entrepreneurs to launch a rail system. The clamour for an Indian railway network was fuelled, in part, by British businessmen who saw the new lines thrusting inland as levers opening up new markets and sources of raw materials and came to fruition in the middle of the 19 th century. Two companies were created and, with assistance from the East India Company, railways were hastily constructed across India during the next half century. The technological advances epitomised progress and would be useful for everything from eliminating Hindu Nationalism to profiting British businessmen who were encouraged from the beginning to invest heavily with the promise of a good return on their money.

Railways were to transform the story of India and to play a major role in the lives of both of Kashfis parents.

William OCallaghan would one day tell journalists that, both the missus and me were born in London, and that Joan lived in India while he worked as a traffic superintendent with Indian Railways implying, strongly, that they were simply living there for his job. The truth is that both William and Phoebe were born into railway families who were already rooted in India. The two Henrys (Henry OCallaghan, Williams father, and Henry Shrieves, Phoebes father) were engine drivers who worked for the Bengal Nagpur Railway (BNR). William himself was working as the station master in Chakradharpur when he met Phoebe.

In the Railway Lines each employee rented their home from the company. Accommodation was allocated according to their status junior staff in a tenement or two storey flat, while middle management had spacious bungalows with servants quarters at the back of the compound. Barrack-like living quarters were provided a little way off from the bungalows for the washer-men, sweepers, gardeners and cooks. There were tarmacked roads, stone slab pavements, hedges, shady trees and areas for children to play in. Social conduct was well defined and adhered to rigidly; a hierarchy was maintained at all times. The British and the Irish held the top jobs but the railways functioned through the mid-and lower-level jobs which were held by Anglo-Indians. Due to the ease with which the community got the jobs during the British era, Indians dubbed it their grandfathers property.

Children attended the Railway School unless, like the OCallaghan children, they were sent away to boarding school. Religion played a central role in the community. Grace was said before every meal, whether you were Anglican or Catholic and church to which the women wore their best clothes with scarves or straw hats was attended twice on a Sunday. The dresses were specially tailored, according to designs from the English Fashion Book sent over from England, by Muslim tailors who worked on the verandas of the houses and were paid according to the number of dresses sewn on the day. But it was the Institute which was the heart and soul of each Railway Colony. Much like the traditional Working-Mens Clubs in Britain (except that the Institute was designed for families) there was a range of social activities as Olive Lennon, a former teacher from a railway school recalled: there was never a dull moment; movies, card games and heavy-schedule social evenings.

For Anglo-Indians this way of life lasted for less than seventy years from the birth of the railways until India gained her independence. Once the Anglo-Indian community no longer enjoyed the exclusive privileges afforded to them by the British many left India altogether. Those that stayed, and wanted to remain on the railways now competed alongside Indians for jobs which had always been theirs under British rule.

PHOEBES STORY

The story of the OCallaghan family in India is fragmented by denial, doubt and the corrosive consequences of British Imperialism. Phoebe Shrieves, Kashfis mother, is the key to most of this narrative. Her story represents one aspect of British rule in India from the eighteenth-century onwards.

She was born Martha Phoebe Melinda Shrieves in Chakradharpur in 1907, some one hundred and twenty years after her great-great-grandfather, John Shrieves the Elder, is believed to have arrived in India. Little is known about Shrieves the Elder other than that he was born in England and that, in 1783, he probably boarded a ship named Francis and sailed to India. Probably because although a John Shreeves arrived in India in 1783 there is no record of the Francis sailing in 1783 and when it sailed the following year there is no record of a John Shreeves being on board. What we do know for definite is that thirteen years later he was married and living in Trichinopoly, a district in the Presidency of Madras in British India. To put this in its historical context and understand why Shrieves the Elder found himself so far from home at the end of the 18 th century it is necessary to know something about the British East India Company. The organisation, described by William Dalrymple as a powerful multinational corporation whose revenue-collecting operations were protected by its own private army, occupied and controlled vast swathes of the Indian continent between 1774 and 1858. They were a London trading company who were granted an exclusive charter to trade with India by Queen Elizabeth I. How a British company transformed themselves from traders to governors is a complex and bloody story of greed, opportunism, violence and chaos. This was the toxic foundation upon which the jewel in the crown of the British Empire was built. Following the first War of Independence in 1857, when Indian troops in the British army tried to overthrow the British Raj (described by one historian as an interlude at which no Englishman of intellectual honesty can look without embarrassment and unhappiness.), the rule of the British East India Company was transferred to the British Crown (known as the British Raj raj literally translates as rule in Hindi) and Queen Victoria was declared Empress of India.