Published by Black Inc.

in association with the University of Melbourne and State Library Victoria.

Black Inc., an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street, Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

www.blackincbooks.com

State Library Victoria

328 Swanston Street, Melbourne Victoria 3000 Australia

www.slv.vic.gov.au

The University of Melbourne

Parkville Victoria 3010 Australia

www.unimelb.edu.au

Copyright Michelle de Kretser 2019

Michelle de Kretser asserts her right to be known as the author of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

9781760640194 (hardback)

9781743821077 (ebook)

Cover design by Peter Long and Akiko Chan

Typesetting by Marilyn de Castro

Photograph of Michelle de Kretser: Mayu Kanamori

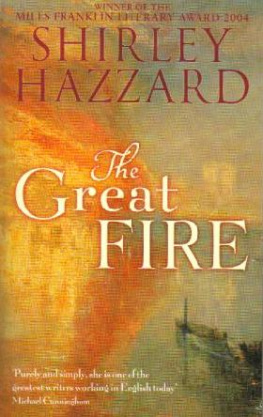

Photograph of Shirley Hazzard: Eamonn McCabe/Getty Images

A Spark of Laurel copyright 1958 by Stanley Kunitz, from The Collected Poems by Stanley Kunitz. Used by permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

A Map of Verona by Henry Reed, 1942. Used by permission of the Royal Literary Fund.

For Sarah Lutyens

Works of art can be more important than

anything critics can say about them.

Shirley Hazzard, We Need Silence to Find Out What We Think

Ive carried in my head

For twenty years and more

Some lines you wrote

Stanley Kunitz, A Spark of Laurel

AN ENDING

I n December 2016 an email came to tell me that Shirley Hazzard had died. I read it and began to cry. It was a response to the crushing Too late! that attends all our negotiations with the dead. I was a reader weeping because now there would be no more books; I was a writer weeping because now I could never write to Hazzard, telling her what her work meant to me and thanking her for it.

The tears went on, returning steadily, stealthily as day followed day. This silent, unstoppable cascade embarrassed me. It felt excessive. Hazzard was eighty-five. I knew that shed been ill for some years, latterly spending the greater portion of her days asleep. She had been well cared for during her decline. Id never met her, never corresponded with her I couldnt argue any personal tie. Mutual friends seemed largely undisturbed by her death; it was, as they pointed out gently, a good ending and not unexpected. My weeping felt imposterish, as if I were claiming a connection that didnt exist.

At some point in those sorrowful days there came into my mind Jacob Burckhardts declaration, quoted by Hazzard, that Italy belonged to all who fell under its spell by right of admiration. So, fittingly, it was Hazzard herself who provided the explanation for my tears: they flowed by right of admiration.

HOW TO ACCOUNT FOR IT?

H azzard was the first Australian writer I read who looked outwards, away from Australia. Her work spoke of places from which I had come and places to which I longed to go. It conjured cities and rooms: sociable spaces. Yet what she had to say was expansive, not enclosed I felt enlarged by it, my view widened. It was reading as an affair of revelations and gifts. It fell like rain, greening my vision of Australian literature as a stony country where I would never feel at home. Splendour had entered the scene.

She describes a fresco: The impression it made was unaccountable; there was nothing in any of its details to suggest the splendour of the whole.

Faced with writing about her work, I ask myself: how to account for the impression of splendour?

Its striking how frequently Hazzard evokes the value of phenomena that resist description. She notes the incommunicable grandeur of a landscape, and the silent, inestimable losses that modernity brings. Its hardly unusual for a writer to appreciate the expert articulation of experience, but its rarer to find one who prizes what expertise cant say. Unaccountable is a word that recurs when Hazzard writes about literature or painting. It acknowledges the mystery that resides in art, as well as the contingent nature of our response. A book comes to find you at a particular season of your life. Afterwards, nothing is the same.

I decide to quote Hazzard extensively in this essay. I repeat my mantra: literature lives in sentences. Quotation seems the best way of indicating what I admire in Hazzard as well as giving readers unmediated access to her prose.

As soon as I begin, Im beset by doubt. I have the impression that Ive been entrusted with something large and shimmering and whole, and that in attempting to hand it on, Im reducing it to shards. Instead of conveying the moonlight, all Im showing is the glitter of broken glass.

Julian Barnes cites Degas: Do you think you can explain the merits of a picture to those who do not see them? ... Among people who understand, words are not necessary, you say, humph, he, ha, and everything has been said.

Humph, he, ha.

STRAYA

O ne reason for the affinity I feel with Hazzard is the question mark that hovers over our right to be considered Australian: in her case, because she left the country at the age of sixteen; in mine, because I didnt arrive until I was fourteen.

Born in 1931, Hazzard described the Australia in which she grew up as a country where sameness was a central virtue. It was a remote, philistine country in those years, and very much a male country, dominated by a defiant masculinity that repudiated the arts.

Others of Hazzards generation have said the same thing. And with Hazzard, there was the additional factor of her youth; her experience of Australia was necessarily limited, confined to the circles of home and school. Children mistake their families for the world how can they do anything else?

Yet, from a passage in The Transit of Venus describing the Bell sisters childhood in Sydney: Once in a while, or all the time, there was the sense of something supreme and obvious waiting to be announced.

In middle age, Caroline Bell expresses a wish to return to Australia to see what she was incapable of seeing as a child.

In The Transit of Venus that great narrative of observation an antipodean way of seeing is described as a clear perception unmingled with suspiciousness. Antipodean seeing is radical, interrupting the smooth flow of acceptance. It draws attention to what has been normalised and rendered invisible. Caro sees a heavy wardrobe in a room and thinks of the men who had to carry it up the stairs. Her insight is connected to the antipodean origins that make her an outsider in England; excluded from power, she can see how it works.

Antipodean, a term often used patronisingly in the northern hemisphere, is recouped here by Hazzard. Through spending time with Caro, Ted begins to see as she does. Antipodean seeing is accurate: a compliment smuggled into the most Australian of Hazzards books.

Down the years, whenever Ive mentioned my admiration of Hazzard, there has always been someone no, let me be accurate: there has always been an older man who wields intellectual and cultural power to inform me that Im quite wrong. Her Boyer Lectures of 1984, published as