Acknowledgments

All work, whether monumental or modest, is never the result of a solitary effort. I owe thanks to people too numerous to name who supported and assisted me in the production of this work. I thank the American Council of Learned Societies who supplied me with a fellowship that allowed me to take a year from teaching in order to travel to various locations to examine resources and interview informants; without the support of the ACLS fellowship program, this work might never have been undertaken. I thank Robert Farris Thompson, who agreed to read an early draft of this work. I am indebted to Marquetta Goodwine, known to the residents of St. Helena Island, South Carolina, as Queen Quet, Queen of the Gullah people. I thank my generous informants Ms. Mary; Arthur Flowers; Brother Gregory; Papa Ce; Dancingtree Moonwater; Hougan Vincent, known to some as Papa Cosmos; Phoenix Savage; and Djenra Windwalker, who fight to maintain the old tradition, to keep African American Hoodoo alive, and who serve the African American community in the names of our ancestors. I give special thanks and honor to Mama Zogbe, chief Hounon-Amengansie of West African Mami Wata Vodoun. Thank you for keeping the faith. I thank Professor James Turner of the Africana Studies and Research Center at Cornell University, who told me the story of his aunt's potential arm amputation by white medical doctors and her healing encounter with Hoodoo medicine. I thank all the African Americans who told Hoodoo stories and renewed the moribund faith in us even as the tradition was facing transformation by marketeers and confronting impending death.

I owe special thanks to all the reference librarians and archivists, from Mr. Willie Maryland of the Montgomery state archives in Montgomery, Alabama, to Catherine C. Khan, the archivist at the old Touro Infirmary in New Orleans, who allowed me to examine the original admission logbooks and records from 1855 to 1861 in search of information on Hoodoo and slave health care. I owe thanks to both Grace Cordial in special collections at the Beaufort, South Carolina, public library, who was helpful in directing me to vertical file materials on local Hoodoo, and the librarian in the Cleveland, Ohio, public library, who allowed me to examine several uncataloged boxes of Newbell Niles Puckett materials. The librarians at the Tallahassee, Florida, state archives pointed me to several boxes of interview materials from both Zora Neale Hurston and the Works Progress Administration writers. I offer a special thank-you to the library staff at the Amistad collection in pre-Katrina New Orleans, who directed me to copies of missionary records as well as public health interviews from the 1930s conducted with informants on the street about their healing practices and beliefs in Hoodoo medicine. And a special thank-you to the border control agent in Laredo, Texas, William Graves, who sent me a dozen High John roots. To Professor Mark Leone of the University of Maryland, College Park, who allowed me to examine and to photograph the artifacts from an antebellum slave conjurer's cache, circa the 1820s, uncovered in an archaeological dig in southern Virginia: Thank you for the afternoon.

Last but not least, I thank my family and my dear late husband, Lathan Donald, who supported me when I became ill and had to stop working on the manuscript. He nursed me, fed me in bed, and encouraged me to return to work whenever I became discouraged. Above all, I thank God, known to me as Olodumare, but who is called by many names. I thank my ancestors, who always had my back, and my personal orisha father, Ogun, and mother, Oshun, for the will to keep fighting and for the wisdom to know when to change tack in the battle. Finally, I thank all those African American believers and practitioners of the Old Black Belt Hoodoo tradition for holding on until we could arrive.

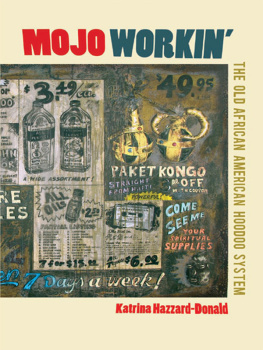

Katrina Hazzard-Donald

is an associate professor of sociology,

anthropology, and criminal justice at

Rutgers University-Camden and the

author of Jookin: The Rise of Social Dance

Formations in African American Culture.

The University of Illinois Press

is a founding member of the Association of American University Presses.

Designed by Jim Proefrock

Composed in 9.75/13 ITC New Baskerville

with Poplar display

at the University of Illinois Press

Manufactured by Thomson-Shore, Inc.

University of Illinois Press

1325 South Oak Street

Champaign, IL 61820-6903

www.press.uillinois.edu

Bibliography

Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. Greenwich, Conn.: Fawcett, 1959.

Adams, George C. S. Rattlesnake Eye. Southern Folklore Quarterly 2 (1938): 3738.

Adams, Samuel Hopkins. Dr. Bug, Dr. Buzzard, and the U.S.A. True (July 1949): 36, 6971.

Aimes, Hubert H. S. African Institutions in America. Journal of American Folklore 18, no. 68 (January-March 1905): 1532.

American Social Hygiene Association. Preliminary Report of a Survey of Medical and Educational Aspects of Social Hygiene in the City of New Orleans. New York: ASHA, 1931. (Manuscript in the Amistad Collection, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana.)

Anderson, Ann. Snake Oil, Hustlers and Hambones. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2000.

Anderson, Jeffery. Conjure in African American Society. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

Aptheker, Herbert. American Negro Slave Revolts. New York: International, 1969.

Aptheker, Herbert. Maroons within the Present Limits of the United States. Journal of Negro History 24, no. 2 (April 1939): 167184.

Arcaya, Pedro M. Insurrecion de los negros de la Serrania de Coro. Caracas, Venezuela: Instituto Panamericano de Geografia e Historia, publ. no. 7, 1930.

Backus, E. M., and Ethel Hatton Leitner. Negro Tales from Georgia. Journal of American Folklore 25 (1912): 125135.

Bacon, Alice Mabel. Work and Methods of the Hampton Folklore Society. Journal of American Folklore 11, no. 40 (January-March 1897): 1721.

Baer, Hans. An Anthropological View of Black Spiritual Churches in Nashville, Tennessee. Central Issues in Anthropology, vol. 2, no. 2 (1980): 5368.

Baer, Hans, and Yvonne Jones, eds. African Americans in the South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992.

Bailey, Cornelia Walker, with Christena Bledsoe. God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man. New York: Doubleday, 2000.

Balfour, J. H. Notice of Some Plants Which Flowered Recently in the Edinburgh

Botanical Garden. Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal 44 (1848): 200205. Banks, Ann. First Person America. New York: Vintage Books, 1981. Barnes, Sandra. Africa's Ogun: Old World and New. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

Barrows, Julie. Herb Cures in an Isolated Black Community in the Florida Parishes. Louisiana Folklore Miscellany 3, no. 1 (1970): 2527. Bascom, William R. Ifa Divination: Communication between Gods and Men in WestAfrica. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1969. Bascom, William R. Sixteen Cowries: Yoruba Divination from Africa to the New World.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Bastide, Roger. The African Religions of Brazil.