Contents

This biography is dedicated with respect, admiration, and gratitude to the following:

A LFRED B ESTER, W ILLIAM G OLDMAN, H ENRY M ILLER, P HIL O CHS, H AROLD R OBBINS, AND A NDREW S ARRIS.

In my youth, their work ignited the fires of my own creative passions, passions that burn within me still.

And to the memory of S HEN Z HONGQIANG , my eternal Shanghai brother-in-peace. Wherever your spirit rests today, it is also here.

He was the most naturally gifted actor I ever worked with. It was all instinct, all emotion; I dont think it came from training or techniqueit came from forces deep within him.

THOMAS MITCHELL

The story goes that when the news first hit Hollywood of Ronald Reagans ambitions to be president, Jack Warner, the legendarily blunt mogul, responded, No, Jimmy Stewart for president, Ronald Reagan for best friend.

RELATED BY DAVID ANSEN IN NEWSWEEK

Thats the great thing about the moviesafter you learnand if youre good enough and God helps you and youre lucky to have a personality that comes acrossthen what youre doing isyoure giving people little, little, tiny pieces of time, that they never forget.

JIMMY STEWART, QUOTED BY PETER BOGDANOVICH

I would prefer to place James Stewart in a triptych of equal acting greatness with Cary Grant and James Cagneyand say that Stewart is the most complete actor-personality in the American cinema, particularly gifted in expressing the emotional ambivalence of the action hero.

ANDREW SARRIS, FILM HISTORIAN AND CRITIC

All the women want to mother Jimmy Stewart, thats his great quality.

FRANK CAPRA

Stewart was closer to a representation of Hitchcock himself than any presencehis image was reshaped by Hitchcock to conform to much in his own psyche. He is, in important ways, what Hitchcock considered himselfwith an alter ego attractive enough to engage the sympathies of his audience. Cary Grant, on the other hand, represents what Hitchcock would like to have been.

DONALD SPOTO, HITCHCOCK BIOGRAPHER

When something is happening to a star, a Cary Grant or a James Stewart, the public feels it more.

ALFRED HITCHCOCK

A show business optimist? Thats an accordion player with a beeper.

JOHNNY CARSON

Introduction

James as in Jimmy, Art as in Life

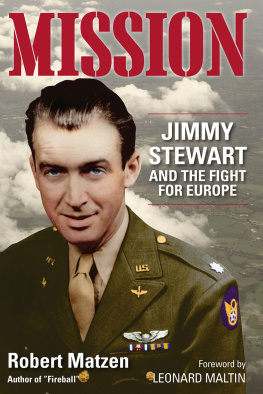

A figure races in the darkness along a series of rooftops, like the flash of an idea across the mind. Just behind, an older, uniformed officer is in hot pursuit, and still farther behind him a third, tall and thin plainclothesman, bent like a fox at the hunt, struggles to keep up. Shots ring out, revealing the first is a criminal, running from the others. He makes desperate rooftop-to-rooftop leaps, the last across a dark, sheer-drop alley. The older and slower uniform makes it as well. The plainclothesman tries next, but, although thinner and apparently younger than the uniform (but not as lean or youthful as the thief), he doesnt quite get over. Instead, his body slams onto the side of the steep A-frame. He slips downward toward the edge. He dangles by his fingertips from a dangerously unhinged gutter drain. The uniform turns back to rescue the plainclothesman. He inches closer down that slippery slope, reaches out to grab the plainclothesmans wrist, loses his footing, and, with a final scream that rips apart the night, falls to his death. Horrified, the plainclothesman hangs, suspended and helpless, looking over his shoulder into the hungry, deadly abyss that eagerly awaits him.

These are the spectacular and spectacularly disturbing opening moments of Alfred Hitchcocks 1958 classic Vertigo, in which James Stewart, at the absolute peak of his acting form, plays the tragically flawed, insanely obsessed, and deeply existential John Scottie Ferguson. In Vertigo, Stewarts style of acting perfectly reflected not only his familiar cinematic personathe ordinary man adrift, perhaps trapped in an abnormal world, longing to find his rightful physical, emotional, and spiritual place in itbut also to a greater degree than in any other movie he made, his real-life personality.

Stewart, like Ferguson, was withdrawn and a wanderer, a Presbyterian soul who fought against the perils of losing control of his own closely held emotions. He grew up in the shadow of an imperious, distant, at times completely absent Godlike father to become a man continually hanging by his fingertips above the canyons of disillusionment that beckoned throughout his otherwise high-flying and glorious life.

The crucial difference between the character Scottie and the actor Stewart lay in their relative sanity. Scotties ultimate undoing is brought about by his belief in the power of possessive, obsessive sex as a curative, a liberating, redemptive act even after it has caused the death of his (so-called) loved one, a fatal trap disguised as a letting go that leads him eventually to the brink of suicide. The foundation of Jimmys sanity, meanwhile, lay in his abject refusal to ever let go of his unwavering faith in the curative, redemptive liberation of love as the reflection of the moral righteousness of Western Christian ideology. These beliefs, in turn, helped him realize the power of his continual on-screen persona, that of a spiritually based, romantic all-American beacon of enlightenment to millions of Americans for more than half a century of turmoil and upheaval, from the depths of the Great Depression, through World War Two, the Cold War, Korea, Vietnam, and up to and including Americas early involvement in the ongoing conflicts of the Middle East.

The idiosyncratic stylistics of Stewarts screen acting, the tools with which he used to project the inside of his characters onto the dreamlike surface of the silver screen, included a repertoire of physical tics, exaggerated gestures, and slowed-down jaw-boning that generation after generation (and multitudes of impersonators, both professional and party-level) came to recognize as Stewartisms. Some were as simple as appearing to shake hands with himself during a scene while having a conversation with someone else (or, as in the case in Henry Kosters Harvey [1950], with some unseen other), the country-boy crackle of honesty and confusion in a high-pitched, drawn-out drawl, the slow, silent, frustrated shake of his head. Others were more subtle and complex, like the depth of his soul that shone so clearly through those piercing Pennsylvania steel blue eyes. Anthony Mann, a director who guided the actor through eight films in an intense five-year period during the first half of Stewarts greatest sustained period of filmmaking, the fifties, once observed, All the great stars that the public love have clear eyes. The eyes do everything: theyre the permanent reflection of the internal flame that animates the hero. Without those eyes, you can only aspire to second-string roles.

Indeed, Stewarts otherwise ordinary facewith its delicate, translucent skin so thin that the tiny blue veins on his cheeks were always visible, even under makeup, its square jaw rounded to just this side of soft, and its nose a bit too thick to make him leading-man handsomewas artistically lit by those startling blues that illuminated the passionate longing that lurked within. Whenever his brows arched upward, it was his eyes that gave in to helpless supplication, while the top of one wrist pushed back and forth against the bottom of his dropped jaw, making it seem as if he were rubbing away some recurring pain, physical or otherwise.

Next page