Everybody wants to be Cary Grant. Even I want to be Cary Grant. I have spent the greater part of my life fluctuating between Archie Leach and Cary Grant; unsure of either, suspecting each. I pretended to be somebody I wanted to be until finally I became that person. Or he became me.

C ARY G RANT

He was the best and most important actor in the history of the cinema The essence of his quality can be put quite amply: he can be attractive and unattractive simultaneously; there is a light and dark side to him but, whichever is dominant, the other creeps into viewHe was rather cheap, and too suspicious he was, very likely, a hopeless fusspot as man, husband, and even father. How could anyone be Cary Grant? But how can anyone, ever after, not consider the attempt?

D AVID T HOMSON

Where among Screwball stars William Powell, say, was one- dimensionally debonair, Ray Milland bland, Don Ameche plebeian and suspiciously Latin, Henry Fonda the soul of uprightness, and Gary Cooper a prodigy of plain speaking (though in some of these cases they played against type), Grant is marvelously protean, the multifarious embodiment of all these qualities and more.

B RUCE B ABINGTON AND P ETER W ILLIAM E VANS

The heterosexual couple of classical cinema encompassed within them and between them all sorts of shifting alliances: dyads, triangles, quartets, the great stuff of Freudian narrative, concealed and revealed. You don't have to see the perverse shadings and alternative readings in the old films, but they are there: to deny all the homosexual, bisexual, and heterosexual possibilities inherent in the coming together of, say, Dietrich or Garbo and their lovers; Grant and his; or practically all of the screwball couples; or practically all star couples, is to read film literally and to insist on making unequivocal something whose very charm, whose layered inferences, were based on the equivocal.

M OLLY H ASKELL

Star-gazing can be said to constitute one of the mass religions of our time.

A NDREW S ARRIS

Out of chaos comes the birth of a star.

C HARLIE C HAPLIN

INTRODUCTION

A lthough he would go on to star in six more Hollywood features, Cary Grant's thirty-four-year film career crested with his dual performance as George Kaplan/Roger O. Thornhill in Alfred Hitchcock's North by Northwest. Released in 1959, the film signaled the commercial and artistic peak not just of Grant's magnificent body of work but of Hitchcock's as well. One of the celebrated director's cleverest (and silliest) movies, North by Northwest afforded the increasingly maudlin filmmaker the chance to muse upon his most primal obsession, his own mortality, in this instance projected onscreen by the adventure of his favorite leading man, Cary Grant, in what would become for both their wildest flight of cinematic fancy.

Kaplan's faked murder two-thirds of the way through the film forces the question of whether he actually is who the others believe him to be, someone entirely separateRoger O. Thornhillor whether he really ever exists at all. Out of this question a larger one emerges: is Kaplan the creation of the Hitchcock-like CIA operative (Leo G. Carroll) who has, thus far, remained largely unseen while cleverly directing the either/or/neither Kaplan/ Thornhill's every move? Or is he someone, or something, else, an externalized elaborate fantasy, perhaps, of Thornhill's most repressed desires for an idealized life of exciting adventure, of romance, of meaning?

Grant must have found North by Northwest's multiple plot twists enormously appealing, as they so clearly reflected his own lifelong struggle to balance the great circus ball of fame with a desire to live an intensely private real life, a life whose very survival depended upon the enormous popularity of his synthetic movie star persona.

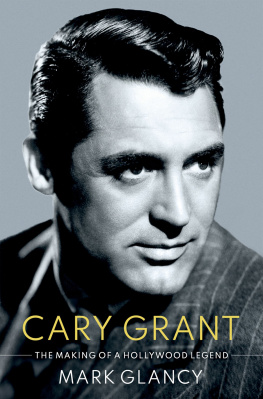

Indeed, onscreen Cary Grant was nothing less than perfect, the man from dream city, as Pauline Kael once described him, the handsome devil every man dreamed of being and the devastatingly handsome lover every woman dreamed of being with. To the world that knew and loved him only through his films, he was worthy of worship and adoration, even if everything from his famous self-confident swagger and unflappable romantic charm to his magical name's ultra-British iambic flow was as calculated and artificial aswell, as George Kaplan.

IN 1966, SEVEN YEARS AFTER the release of North by Northwest, Cary Grant officially retired from making movies for the third and final time; by then his place high in Hollywood's pantheon of cultural icons was well assured. In the twenty years of life he had left, his gait inevitably slowed, his skin thickened, his hair grayed, and his shoulders stooped, until, at eighty-two, he quietly joined Hollywood's league of legendary dead. Yet because of the glorious legacy of his films, to present and future fans he would remain forever young, eternally alluring, and preternaturally beautiful, the quintessential motion picture personification of the middle third of the American twentieth century's definition of tall, dark, and handsome. Once he became a star, with few notable exceptions, Cary Grant never ventured too far from Cary Grant and was always readily identifiable by the crystalline dazzle of his smile, the rolling shuffle of his slightly bow-legged walk, the suede slip-slide of his voice, that irresistible cleft in his chin, and those unforgettably piercing topsoil-brown eyes that connected him to the worldthe twin-beam projectors of his inner emotions.

Movie stars are the magnified external images of society's idealized dreams, hopes, and fantasies. Filmgoers associate with these stars to such a degree that their physical beauty becomes a social metaphor for moral and emotional perfection. It is the reason they are so worshiped at the peak of their popularity, and why the crest of their stardom rarely lasts longer than five years. In film time this translates into perhaps a half-dozen major roles for a leading man, and even fewer for a woman, before reality crashes their endless party and irrevocably separates them from their fans. A once-flawless face's first wrinkle often signals the beginning of the descending arc of one's cinematic shooting star.