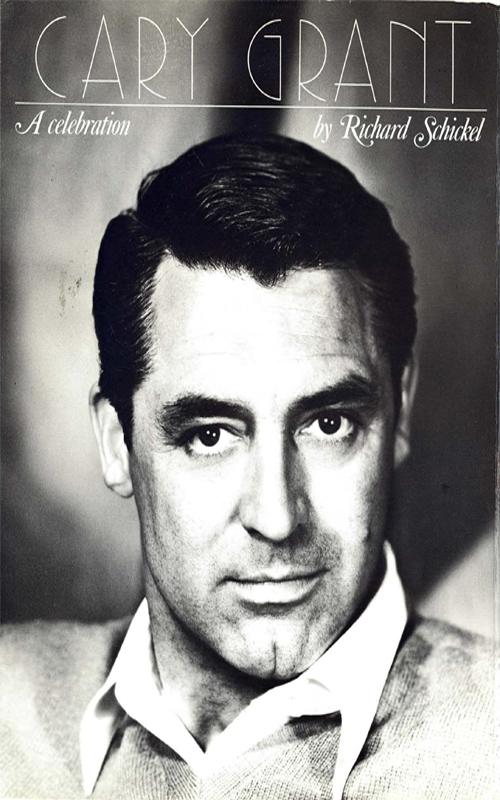

COPYRIGHT 1983 BY RICHARD SCHICKEL

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY ELECTRONIC OR MECHANICAL MEANS INCLUDING INFORMATION STORAGE AND RETRIEVAL SYSTEMS WITHOUT PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER, EXCEPT BY A REVIEWER WHO MAY QUOTE BRIEF PASSAGES IN A REVIEW.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: November 2009

ISBN: 978-0-316-09032-2

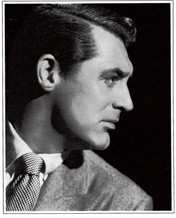

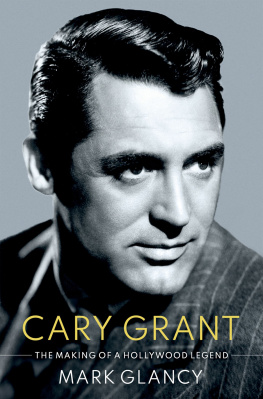

DESPITE THE VAST ATTENTION THAT HAS BEEN paid to movie stardom over the seventy year life of that institution, despite the endless interviewing and profiling of its exemplars that continues to proceed apace, the process by which a great and enduring star personality is created and sustained in the public eye is one of the least intelligently examined phenomena of. popular culture. Mostly critics, journalists and the audience have contented themselves with the faintly contemptuous belief that movie stars play themselves. This has been considered a lesser act of creation than the conventional role playing of the stage as if ones self does not infuse the interpretation of any role, even the classical ones and as if playing oneself were easy, when in fact it is the most difficult part anyone can undertake, given the confusing, literally self-contradictory mass of data at hand, and the problems subjectivity imposes on the task of selecting and presenting the self or perhaps more properly a self.

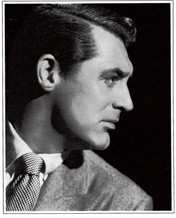

To play your self your true self is the hardest thing in the world to do. Watch people at a party. Theyre playing themselves but nine out of ten times the image they adopt of themselves is the wrong one The speaker knows whereof he speaks, for the speaker is Cary Grant. His choice of words is significant, suggesting that all of us, screen stars or not, have a large range of selves available to us when we set forth on the path of self-portrayal. We are not realistic novelists after all; we cant put everything in, not even all the good bits. We have to pick and choose among the images within our range, stress one quality now, another then, and hope that over the long run our public, be it large or small, will more or less get the idea of us and that it will be a pleasant one.

Selectivity always suggests art and, in the case of the very few stars who achieve the magnitude of Cary Grant, art of a very high and subtle order. Indeed, the evidence both of our eyes and of such testimony on the point that the star himself has offered, suggests that Grant went further than most in that the screen character he created starting some time in the mid-1930s, drew on almost nothing from his autobiography, was created almost entirely out of his fantasies of what he would like to have been from the start, what he longed to become in the end. He has in fact said that he first created an image for himself on the screen, then endeavored to learn to play it off-screen as well as he did on. This is not an unknown phenomenon. Most stars to some degree become what they have played over the course of the years. But the refraction is more intense in Grants case, and the more interesting therefore.

By this I do not mean to imply that Grant has totally eliminated from his screen presence all traces of his humble and troubling childhood. If he had I think he would have had a short and not very merry screen career as a rather vapid juvenile, perhaps, or as a second string leading man of no great distinction. No, there was always something more there clouds constantly scudding across what we perhaps erroneously understood as an entirely sunny personality, sometimes quite blotting out its light. It would be too much to suggest that he hinted at tragic dimensions in any of his roles, but there was always a wariness in him, an uneasy sense that the perfect tailoring might at any time become unravelled, whether through comic or melodramatic encounters. And just as he implied a sense that circumstances might not always be what they at first seemed to be, he also implied a feeling that people and most especially women were not always what they claimed to be either. The possibilities of inconstancy and duplicity seemed always to be on his mind even when they were not necessarily on the minds of director and screenwriter. These possibilities did not make him anxious, but they did make him careful, even (it sometimes seemed) a little bit depressed underneath the charm and ease with which he confronted people and events. It was there that his singularity and his specificity as a character lay; and it was there, finally, that his appeal lay. For it was that hint of a darker knowledgeableness underlying the more confident and seductive forms of knowingness that tugged at the mind and lingered in the memory. And most important humanised him, permitted us our identification with him.

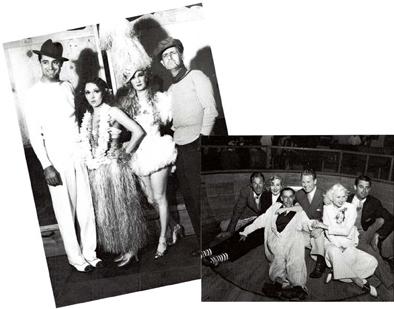

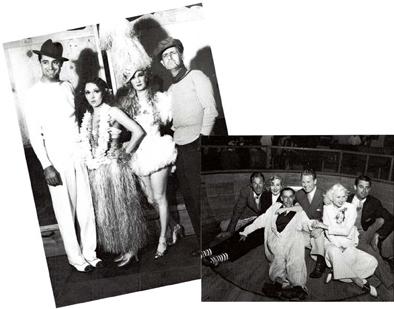

Young man about town: Grant joins a grass-skirted Mary Pickford, the Countess de Frasso and Tullio Carminati at writer Donald Ogden Stewarts costume party at the Vendome,c. 1933. Guests were supposed to come dressed as their favorite stars. Just who this group was impersonating is lost in the mists of memory. Among those identifiable on another night on the town are Randolph Scott, Carole Lombard, Regis Toomey, Toby Wing and, of course, the former Archie Leach.

Typically the assumption that a star plays himself justifies the demand for interviews with him, not to mention the general interest the public takes in allegedly intimate anecdotes and gossip about him. For if a man is only playing himself then manifestly the exposure of that self, a probing of its history in search of its unspoken secrets, will reveal the sources of his magical hold on us. This, I have come to believe, is an error of enormous proportions. And it is especially true of someone like Cary Grant who, if he draws on himself at all draws not on his autobiography as such, but on his most elusive feelings, remembered states of mind, which normally lie well beyond the purview of the written word. I do not believe that in an essay of the kind that follows I have the right or the duty (or the knowledge) to pursue such a course. What I have had available to me is the public record he has left his films and a scattering of what seem to me reliably recorded public statements by and about Grant the actor. From these I have attempted to recreate and interpret his screen character in other words to make a plausible critical evaluation of one of the most delightful and indelible screen personalities ever to insinuate itself into our collective consciousness and unconsciousness. This creation has always seemed to me more complex, more elusive, more subtle than most critics and certainly most gossipists have ever credited it with being. If, inevitably, I have touched on aspects of Cary Grants life, I have, by design, made no effort to intrude on his privacy, to go beyond the public record as he has preferred to let it stand. My hope is that this essay will enrich the readers understanding of what he was up to on the screen, demonstrate that there was more at work before our eyes than simple charm.

Richard Schickel