All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Published in the United States by Pantbeon Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

Toronto.

The Killer Department : Detective Biktor Burakov's eight-year hunt for the most savage

p. cm

1. Serial murders-Russia (Ferderation)Rostovskaia oblast-Case

studies. 2. Sex crimes-Russia (Federation)-Rostovskaia oblast-

Case Studies. 3. Chikatilo, Andrei. 4. Murderers-Russia

(Federation)-Rostovskaia oblast-Biography. 5.Insane, Criminal

I. Title

To Mary C. Carroll, with love and gratitude

1. THE BODY IN THE WOODS

2. THE DETECTIVE

3. THE CONFESSIONS OF YURI KALENIK

4. GIRLS WITH DISORDERLY SEX LIVES

5. THE KILLER'S FEVER

6. THE GAY POGROM

7. A BODY IN MOSCOW

8. DEAD END

9. THE KILLER SURFACES

10. THE SNARE

11. CONFESSION

12. PORTRAIT OF A KILLER

13. THE TRIAL

1

On a sunny Saturday in June 1982, a Russian girl named Lyubov Biryuk left her home in a village called Zaplavskaya to buy cigarettes, bread, and sugar. She did not come back.

Lyubov had just turned thirteen, but she was still a child, short and scrawny. She had light brown hair, cut close and blunt, chubby cheeks, a pug nose, and gray eyes set a little too far apart to be pretty. She was talkative and friendly. One of her uncles thought she was a bit simple, but she got average grades in school. She seemed, in all likelihood, destined to take a place beside her mother among the heavy, tired women who tended the grapes, the cows, the geese, and the pigs at the local sovkhoz, or state-owned farm. She had only one bad habit: though her mother had warned her against it, she liked to hitchhike.

Some of the peasants in the village of Zaplavskaya live in one-story cottages with carved wooden shutters and hntels painted a bright orange or blue, picket fences, tidy vegetable gardens, and perhaps a few plump chickens pecking by the roadside. A few have cars or motorcycles. But Lyubov's family had neither. They lived in a four-family concrete house, owned by the sovkhoz, at the end of a short, dusty path, surrounded by weeds and berry bushes. When Lyubov went on an errand, she walked up the path about seventy-five yards to the paved road, scattering the occasional cluster of sovkhoz geese. There, if she was being obedient to her mother's strictures against hitchhiking, she waited for one of the grimy little buses that occasionally clattered, their sheet-metal panels loose and flapping, down the road to the town of Donskoi.

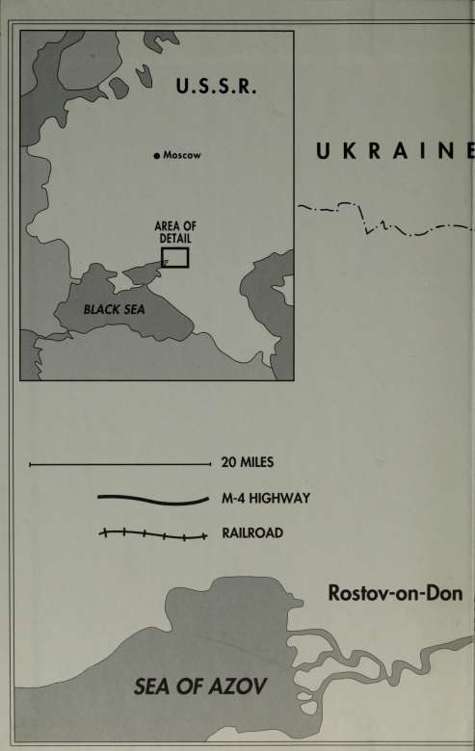

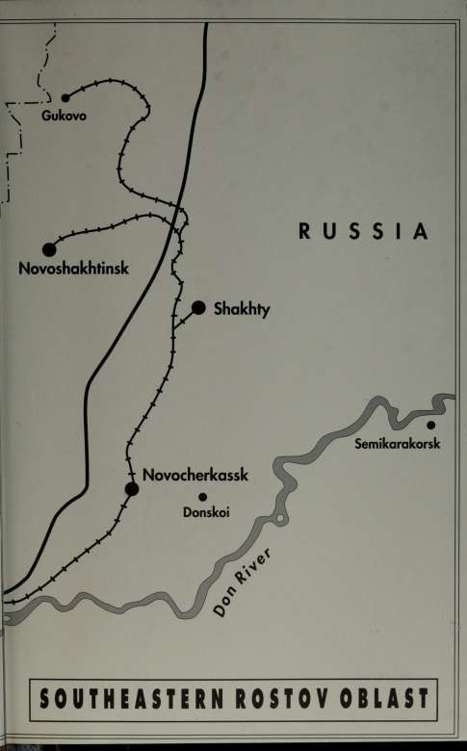

Donskoi, named for the broad, placid Don River that flows a few miles to the east, has the closest stores to Zaplavskaya. Its population, of about five thousand people, works primarily at the Fiftieth Anniversary of the USSR Electric Power Station, whose triple smokestacks tower over the south end of town. The bus from Zaplavskaya to Donskoi stops at a traffic circle a kilometer or so from the power station, in front of a huge, red billboard with portraits of Marx, Engels, and Lenin. From there, a paved walkway leads to the five-story apartment blocks in the town, past a statue of Lenin and a cultural center with an enormous mural immortalizing the deeds of Soviet soldiers in the Second World War. Opposite the mural stands an unnamed little store that then sold vodka, cheap wine, and cigarettes. Farther down the way, there is a grocery store called the Dawn, which generally displays some canned fish, loaves of bread, a few chickens, and a host of flies caught on a swatch of homemade flypaper. Outside, in the summertime, half a dozen peasant women wearing kerchiefs on their heads usually sit on low stools, their tomatoes and green peppers and carrots spread out on newspapers before them to entice shoppers disappointed with the offerings inside. Donskoi's secondary school is around the corner, behind a weedy soccer field.

When Lyubov's mother, Pelagea, returned from work in the cattle barn that evening and discovered that Lyubov had not come home, she assumed that her daughter had gone to visit relatives, most likely her grandmother in Krivyanka, a village five miles up the road. Pelagea, a stocky woman with a mouth full of gold-crowned teeth, had sisters, brothers, half brothers, aunts, and uncles in many of the neighboring villages. Her own parents had divorced after having two children, and her father had gone on to a second marriage and three more children. She had raised the younger ones. Then she had three children of her owna girl named Nadezhda, another named Valya, who picked up a germ in a day-care center at the age of five and died, and finally Lyubov. The absence of her youngest child evoked more annoyance than alarm; Lyubov was supposed to let her mother know when she wanted to visit someone. Since Lyubov's grandmother had no telephone, Pelagea would need to make the trip to Krivyanka to confirm her assumption. She decided to wait until morning.

On Sunday, she rode the bus to her mother's cottage. Lyubov was not there. Nor was she with Pelagea's stepmother, nor with her sister, Nadezhda, in Semikarakorsk. Pelagea spent all Sunday fruitlessly calling on relatives. On Monday, increasingly worried, she walked through a driving rain to Lyubov's school, hoping that one of her schoolmates might have seen her. But the children were taking their final examinations, and the principal would not let her talk to them. Finally, on the verge of desperation, she called her half brother Nikolai.

Nikolai Petrov had done well for a peasant boy from Krivyanka. He was a senior lieutenant on the detective squad of the militsia in Novocherkassk, the nearest city to Donskoi. In Soviet parlance, the police had always been militsia, as if they were just a group of civilians working temporarily until the state withered away. Only bourgeois societies had police. At thirty-one, Nikolai was nine years younger than Pelagea, who had been more a mother than a sister to him. In his youth, he boxed and lifted weights and worked as a construction laborer. He was tough, husky, and handsome, with several distinguishing characteristics. His arms and hands bore a half-dozen tattoos. The knuckles of his right hand bore the letters valya, for his wife, and the knuckles of his left had the four suits of cards: spade, heart, diamond, and club. And he had a full, neatly trimmed beard, just starting to turn gray, which he had started to grow a few years earlier, when a skin condition prevented him from shaving. That gave him the nickname by which everyone on the streets and in the bars of Novocherkassk knew him: the Beard.