The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

O NE EVENING IN EARLY DECEMBER 2003 , I found myself alone in a brightly lit, cavernous office on the fifth floor of the United States Department of Justice, reading a stack of Supreme Court decisions about the Fourth Amendments prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures. At the time I was serving as the assistant attorney general in charge of the Office of Legal Counsel, a position that made me a senior legal advisor to the attorney general and the president. A few weeks earlier, I had concluded that President George W. Bushs secret two-year-old warrantless surveillance program, Stellarwind, was shot through with legal problems. I was working late that night because I was under a deadline to figure out which parts of the program might be saved.

The stakes were enormous. The programs operator, the National Security Agency, was picking up what its director would later describe as a massive amount of chatter about al-Qaeda plans for catastrophic operations in the Washington, D.C., area. I was certainly anxious based on the threat reports I was reading. And yet I increasingly believed that large parts of the program could not be squared with congressional restrictions on domestic surveillancea conclusion I feared would risk lives and imply that hundreds of executive branch officials, including the president and the attorney general, had committed crimes for years.

My thoughts that stressful December evening began with a crisis about national security and presidential power but soon veered to a different turbulent period of my life. One of the cases in my to-read pile was a 1967 Supreme Court decision, Berger v. New York, that restricted the governments use of electronic bugs to capture private conversations by stealth. As my tired eyes reached the end of the opinion, two citations leapt off the page like ghosts: OBrien v. United States, 386 U.S. 345 (1967); Hoffa v. United States, 387 U.S. 231 (1967).

I looked up, incredulous. Neither case was in my stack. So I turned to my computer and printed them out.

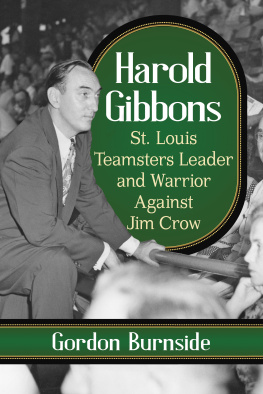

The Hoffa case involved the pension fraud conviction of James Riddle Hoffa, the autocratic leader of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters who would later vanish, on July 30, 1975, in what remains one of the greatest unsolved crimes in American history. The OBrien decision concerned the conviction of Charles Chuckie OBrien, also a Teamsters official, for stealing a marble statue of St. Theresa from a U.S. Customs warehouse in the Detroit Harbor Terminal. The Supreme Court vacated both convictions so that lower courts could determine if the government had eavesdropped on Hoffa and OBrien in possible violation of a new governmental policy and developing Supreme Court jurisprudence. The Hoffa and OBrien cases were important in their day, but by 2003 had become mere footnotes in the long struggle for legal control over electronic surveillance. Thats why they werent in my stack.

After reading the decisions, I immediately saw their connection to each other, and to me. In the 1950s and 1960s, Jimmy Hoffa was the nations best-known and most feared labor leader at a time when unions were consequential forces in American life. Chuckie OBrien met Hoffa at age nine and later served as his most intimate aide for more than two decades. OBrien helped Hoffa bulldoze his way to the presidency of the Teamsters. He was Hoffas trusted messenger to organized crime figures around the country, and was by his side during his seven-year battle with Bobby Kennedy that ultimately sent Hoffa to prison. OBrien escorted Hoffa to his jailers in March 1967, helped secure Richard Nixons commutation of Hoffas sentence in December 1971, and stuck by Hoffa as he struggled to regain control of the Teamsters during his post-prison years.

But in 1974, he and Hoffa had a falling-out. They barely spoke in the eight months before Hoffa disappeared. Soon after Hoffa vanished, OBrien became a leading suspect. He was closely connected to the men suspected of organizing the crime. Based on a slew of circumstantial evidence, the FBI quickly concluded that OBrien picked up Hoffa and drove him to his death.

I knew this history well because Chuckie OBrien is my stepfather. His relationship with my mother, Brenda, was one of the reasons he broke with Hoffa in 1974. I was a pimply twelve-year-old in braces when Chuckie and Brenda wed in Memphis, Tennessee, on June 16, 1975, forty-four days before Hoffa vanished. Ever since Hoffa disappeared, my life has been colored by the changing implications of my relationship to the labor icon, and to Chuckie, whom Hoffa treated as his son, and whom I knew as Dad.

CHUCKIE AND I were very close when I was a teenager, during the height of the Hoffa maelstrom. He was a great father despite his lack of education, the oppressive FBI investigation, and an angry, excessive pride. Chuckie smothered me in love that he never received from his father, and taught me right from wrong even though he had trouble distinguishing the two in his own life. In high school I idolized Chuckie. When I set out on my professional path in law school, however, I renounced Chuckie out of apprehension about his impact on my life and my career. We had barely spoken for two decades by the time of my service in the Justice Department.

I left government in 2004 to become a professor at Harvard Law School, and soon afterward Chuckie and I patched up and once again grew very close. During the next eight years, we often discussed his trying experiences with Jimmy Hoffa and the government juggernaut that since 1975 had sought to pin the disappearance on him. Chuckie had always denied any involvement in Hoffas death. Over the decades he had been consumed with resentment as the government hounded him and tarnished his reputation through incriminating leaks to the press based on evidence that Chuckie was never able to examine or contest. He watched with bitter frustration as hundreds of newspaper stories and nearly a dozen books were published with supposed insider revelations about the crime and his role in it.

Whats bothered me my whole life, Chuckie once told me, is that the government through their devious assholes in the Justice Department turned me into something worse than Al Capone. Yet every time Chuckie tried to explain his side of things on television and radio, he ended up looking worse for the effort.

My conversations with Chuckie made clear why he had been such a poor advocate for himself. He wasnt eloquent and his explanations about his role in Hoffas disappearance sometimes seemed guarded, self-serving, or mendacious. This did not surprise me. Since I was twelve I had often experienced, and frequently laughed at, Chuckies tendency to hedge or fib. The FBI viewed it as a reason not to believe Chuckies alibi on the day of Hoffas disappearance. In a 1976 memorandum analyzing the case, the Bureau noted, OBRIEN is described by even his closest friends as a pathological liar.

The more Chuckie and I talked, the more I came to understand that his adversarial relationship with the truth was influenced by his commitment to Omert, the Sicilian code of silence that he embraced at a young age. Chuckie had a lifelong hatred of ratspeople who broke the code and betrayed their honorand he was alive to speak to me only because he was adept at keeping his mouth shut about certain things. One coping mechanism to ensure that he didnt speak out of school was to shade the truth. I never told anybody what was right, Chuckie once told me, trying to be truthful. I always used what I had to use to divert it.