William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

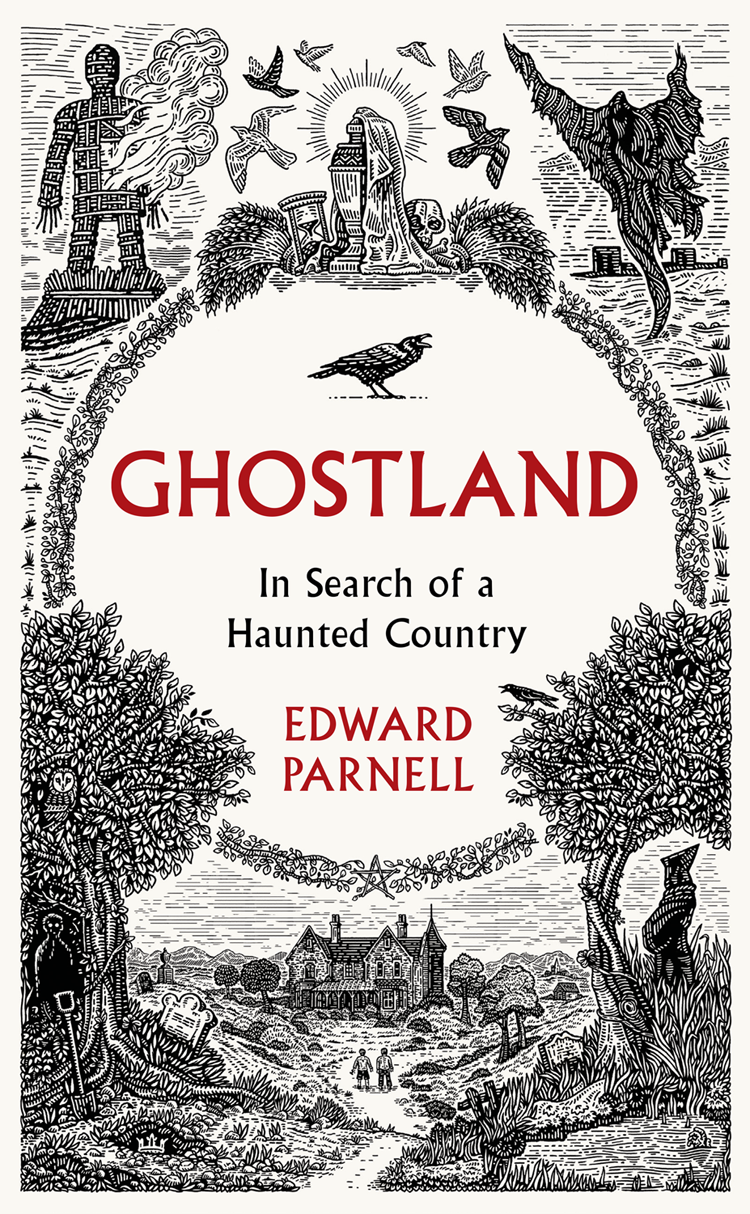

Copyright Edward Parnell 2019

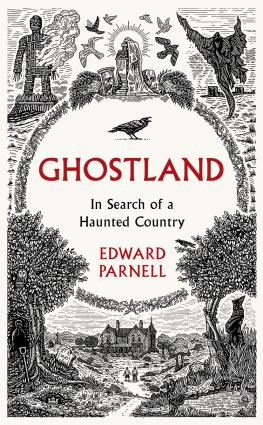

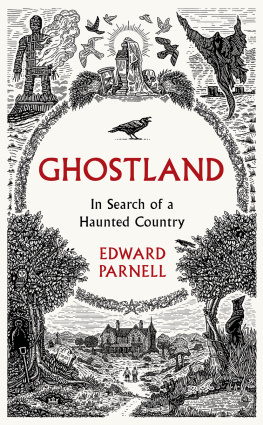

Cover illustrations and chapter initial illustrations are by Richard Wells (www.richardwellsgraphics.com)

All other images are by the author, or from the authors own collection. While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material, in some cases this has proved impossible. The publishers would be grateful for any information that would allow any omissions to be rectified in future editions of this book.

Edward Parnell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The Emigrants by WG Sebald published by Harvill Press, reprinted by permission of The Random House Group Ltd. 1996

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008271954

eBook Edition October 2019 ISBN: 9780008271961

Version: 2019-10-01

For the ghosts

And so they are ever returning to us, the dead.

W. G. Sebald, The Emigrants

Always the ghosts.

Reaching into the past concealed behind the glow-in-the-dark cardboard apparitions that decorated my childhood bedroom, the fascination was there from the start: on a family holiday to Wales, aged four, asking the tour guide in Caernarfon Castle whether we might see the places spectral lady; a few years later, obsessing over Borley Rectory the most haunted house in the world which called out to me from my spine-creased Usborne Guide to the Supernatural World; or, at the Halloween party I begged my mother to let me have (long before such events were a commonplace British occurrence), dressing up as Dracula, my friends as the Wolfman and various grinning ghouls.

The writer M. R. James once wrote: For the ghost story a slight haze of distance is desirable. Thirty years ago, Not long before the war, are very proper openings.

And if I think back through three decades of self-obfuscation, a host of recollections give confirmation.

With me, always the ghosts.

Yet even with hindsight no disquiet comes to me from these memories; they are reassuring, I can find shelter within them. Only later were we to become a phantom family a host of lives lived, then unlived. The disquiet comes when I realise theres no one left to help me reconcile the real and the half-remembered.

So, I must do it myself.

I must attempt to explore that sense so many before me have felt. The shadows they too have glimpsed among the fields, hills and trees of this haunted land.

To lay to rest the ghosts of my own sequestered past.

Chapter 1

It was, as far as I can ascertain, on Christmas Eve of the year 1994 that a young man drew up before the door of his childhood home, in the heart of Lincolnshire. He looked about him with the keenest curiosity during the short interval that elapsed between the fumbling of his keys and the opening of the front door. Inside, he began to study the four programmes available on his television set, pausing before a presentation that caught his eye. The time was five minutes before one oclock, he realised. Christmas Day itself

This, more or less, was how I first became acquainted with the work of M. R. James, my favourite and arguably Britains finest writer of ghost stories. I was home for the holidays during my third year at university and had been into town to celebrate the festivities. A little the worse for drink, I was alone in the living room, as my brother Chris nearly six years my senior was still out with friends. In the morning the two of us would open our presents together before spending the rest of the day at my aunt and uncles. In an attempt to compensate for the houses emptiness and our parents absence, wed started a tradition of labelling our gifts to each other as if from various half-remembered figures from our past: obscure family acquaintances, disliked former teachers, or people who we had given nicknames to like Porkpie, the middle-aged man in the pork-pie hat who was a constant fixture in the pub we frequented, boring anyone whod listen about the supermarket where he worked.

Not ready for sleep, I lay on the sofa and flicked through the TV channels. On BBC Two a grainy drama from the seventies was beginning. What Id chanced upon was an episode of the classic A Ghost Story for Christmas strand: Lawrence Gordon Clarks adaptation of M. R. Jamess supernatural tale Lost Hearts.

Theres a fearful symmetry to this, Ive come to learn, because this particular film was first shown on BBC One a little before midnight on Christmas Day 1973, less than a fortnight after I was born. Had I already witnessed it before as a crying baby perhaps my mother had happened at that very point to switch on the TV set to try and calm my tears? If she had, I doubt she would have found much respite, because the BBC version is a frightening piece of work; I was to find this out some twenty-one years later, when the ghost of a razor-nailed boy and his dark-eyed companion appeared on the screen in front of me.

Through the white gate at the back of the graveyard the ground changes abruptly, the approach from the rectory with its aged, ivy-clad trees replaced by a squat jumble of shrubs and sedge, punctuated by paths that run aimlessly to the water. The lake, as it is called, seems out of place in the west Suffolk countryside, reminding me of one of the shallow, ephemeral coastal lagoons you find in the Camargue. Lifeless trunks point upwards from its greyness like rigor-mortised fingers. The division between land and water is tenuous; there are no banks as such, just a dirty shoreline of mud over which the waves lap, adding to the features temporary feel. This is not a giant puddle left behind by a flood, or some deliberately drowned world, but a spring-fed mere that has given its name to the neighbouring village.

Livermere Lake. The lake where rushes grow, from the Old English laefor-mere. Ive known about this place for a long time too: since my brother saw a vagrant black-winged pratincole here in 1993, a rare hawk-like wading bird. I couldnt join him to see it, which, as a keen birdwatcher, riled me for years (until I finally caught up with one myself on the Norfolk coast) and lent the location an enduring mystique in my head. Only later did I become aware of the connection between Great Livermere and M. R. James.