Chapter 1

The Meeting of the Waters

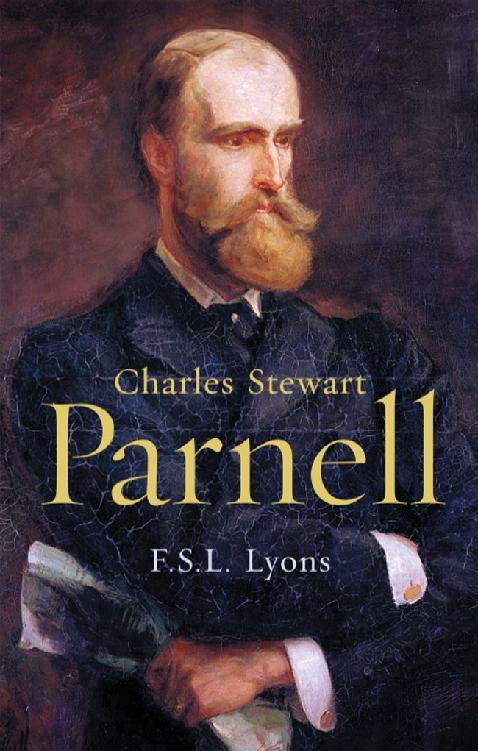

An Englishman of the strongest type, moulded for an Irish purpose.

(Michael Davitt, The fall of feudalism in Ireland, p. 110.)

... above all, Mr Parnell was an Irishman, Irish bred, Irish born, racy of the soil, knowing its history, devoted to its interests.

(Drogheda Argus, 24 April 1875, celebrating Parnells election to parliament.)

I have always held that both in appearance and to a large extent in character Parnell was much more American than either English or Irish.

(T. P. OConnor, Memoirs of an old parliamentarian, i, 97.)

I

A ll the roads that lead from Dublin to the county Wicklow are beautiful. But if there is one more beautiful than the others it is surely the road which rises steeply from Rathfarnham, skirts the head of Glencree where the Sugarloaf mountain floats in the distance, and then, at Sally Gap, follows the route driven through the wilderness by the military after the rising of 1798, until it comes out at Laragh, just above Glendalough. From Laragh it traces the winding course of the little river Avon, through the quiet woods of Clara vale,

When Charles was born the Parnells were comparative newcomers to Wicklow, and indeed to Ireland. The family emerged from obscurity only in the seventeenth century. The first of whom any substantial information survives was Thomas Parnell, a mercer and draper in the town of Congleton in Cheshire, of which town he became mayor in the reign of James I. He had four sons of whom one, Richard, was also mayor on several occasions, and the youngest, Tobias, was a gilder and painter. They appear to have been stout parliament men during the Civil War and this may have helped to persuade Tobiass son, Thomas, to move to Ireland soon after the Restoration. He was far from a penniless migr however, and took with him enough funds to purchase an estate in Queens county where he settled comfortably into the routine of a prosperous landowner. He was the father of two sons through whom the name of Parnell first began to be known outside the family circle.

The elder of these, also Thomas, was born in 1679, entering Trinity College, Dublin, when only fourteen. Graduating in 1697, he was ordained in 1703 and two years later was appointed Archdeacon of Clogher at the age of twenty-six. Like many eighteenth-century Anglican clergy he was a frequent absentee, preferring literary London to rural Ulster. A quietly persistent poet, not much of his verse has survived the test of time, perhaps because the very qualities a later biographer detected in it reflect equally the limitations of the age, of the genre and of the man. His work, says this writer, is marked by sweetness, refined sensibility, musical and fluent versification, and high moral tone.

Perhaps, after all, it was the nature that was excellent, for Thomas Parnell had many friends. They included Addison, Steele, Congreve and Gay, but especially Swift and Pope; it says much for him that both these notoriously difficult individuals held him in high affection. Yet his life was short and marked by tragedy. He married Anne Minchin

The death of Thomas Parnell meant that the Queens county property fell to his brother John, a barrister who sat in the Irish House of Commons, married the sister of a Lord Chief Justice, and became a judge himself. Dying in 1727 he left a son, John, who also sat for an Irish constituency and was created a baronet in 1766. He married the daughter of a judge of the Kings Bench, Anne Ward of Castle Ward in county Down. Their son, the second Sir John, born on Christmas Day 1744, was the first of his line to reach the front rank in politics and since his reputation was to open some important doors for Charles a century later, it is worth looking at that reputation a little more closely.

At first glance, it is certainly impressive. Entering the Irish parliament in 1776, when the American Revolution was creating a favourable opportunity for the Anglo-Irish patriots to free themselves from the close control of the British parliament, Sir John commanded a corps in the Volunteers whose mere existence helped to win the constitution of 1782 to which Charles was later to look back as his prime model for Home Rule. But that constitution was a defective instrument. It did not really break the English stranglehold on the Dublin government, because that government was appointed by, and responsible to, ministers in London, not to the parliament on College Green. The parliament itself, moreover, remained unrepresentative, consisting essentially of Anglo-Irish Protestants who were imbued not with anything resembling modern nationalism, but with the irritation and frustration of a colonial elite, determined to assert itself against the metropolitan power, yet not daring to go too far lest it should have to admit the Catholic majority to the jobs and pensions and connexions which so faithfully mirrored the grander political world across the Irish Sea.

Some of the patriots, it is true, were prepared to move decorously and cautiously towards a progressive emancipation of Catholics. Gradually most of their legal disabilities were removed, until the Irish parliament found itself facing the biggest questions of all whether Irish Catholics should be given the vote and whether, once enfranchised, they should themselves be eligible for election to parliament. On these vexed questions (the first of which was decided in favour of the Catholics in 1793, the second of which had not been solved when the Irish parliament ceased to exist in 1800) Sir John Parnell he had succeeded his father to the baronetcy in 1782 held distinctly conservative opinions. Although the contemporary view of him as an able and, within the elastic eighteenth-century definition of the term, an honest man, may have been justified, those who knew him well found him mentally lazy and firmly anchored to the status quo.

The possession of such views did not, of course, prevent him from climbing the ladder of success. In 1785 he followed his friend John Foster as Chancellor of the Exchequer and in 1786 he became a Privy Councillor. During his fourteen years as Chancellor he did much to reorganize Irish governmental finance on the English model, but the permanence of his work, as of the constitution of 1782 itself, was always