Contents

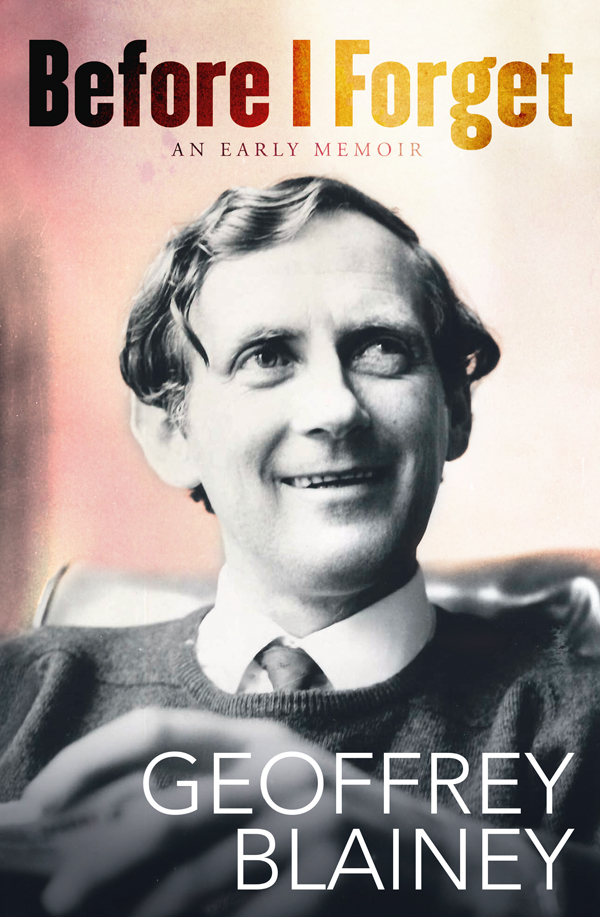

About the Book

At home, encircled by books, I assumed that my writing career, so precarious, would flourish

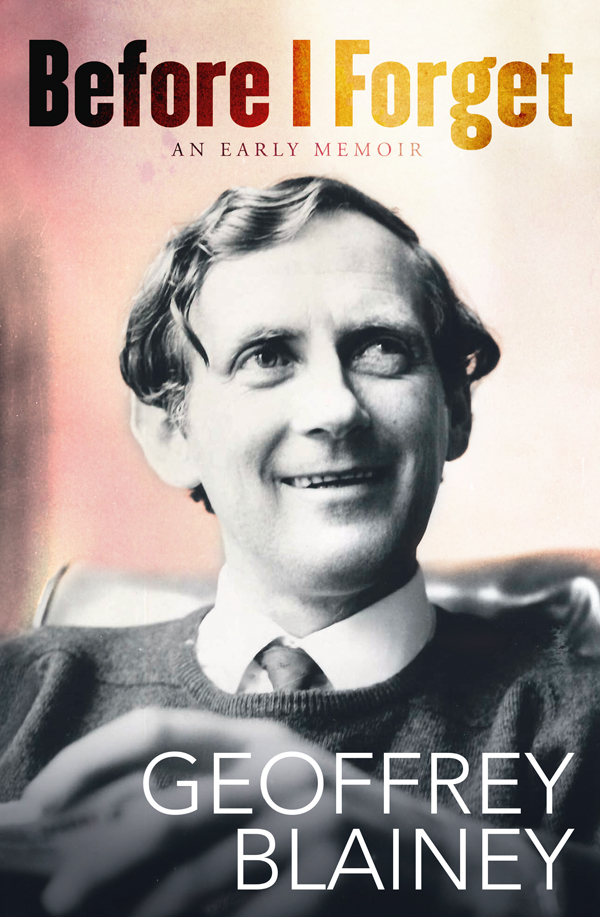

For close to seventy years Professor Geoffrey Blainey has uncovered and chronicled our history. Now in his ninth decade and listed by the National Trust as a Living Treasure, Blainey turns to his own story, reflecting on the first forty years of his life, from his humble beginnings as the son of a Methodist minister and school teacher, to establishing his career as historian and writer.

One of five children, Geoffrey Blainey recalls an unusual childhood spent in regional Victoria, from Terang to Leongatha, Geelong to Ballarat, surrounded by books. These places ignited for him a great affection for the Australian landscape, and a deep curiosity in Australias history. As a Geelong newsboy he developed a thirst for current affairs, following the unfolding drama of the Second World War. He longed to travel, and now living in Ballarat in 1943, he would climb atop the family home to stare out at the Great Dividing Range and imagine a world beyond.

A lucky scholarship to Wesley College further instilled a love of learning, which flourished later at the University of Melbourne as both student under Manning Clark, and as professor. Adventure always beckoned; at the age of seventeen he hitchhiked to Sydney with a schoolfriend to see the harbour that greeted the First Fleet, and also visited the national theatre of Parliament House on the way home to hear Billy Hughes, Bob Menzies and Ben Chifley in action.

Hours spent at Melbournes State Library as a student poring over old newspapers cemented his calling to become a professional historian and writer. His groundbreaking early book The Tyranny of Distance offered Australians a fresh understanding of themselves and catapulted a new phrase into the vernacular. Now the author of over forty books, Geoffrey Blainey believes he has discovered Australias history his own way and is still learning.

Warm, lively and lyrically written, Before I Forget recounts the experiences and influences that have shaped the astonishing mind of Australias most remarkable historian. But in this book Blainey has given us something more a fascinating and affectionate social history in and of itself.

CONTENTS

To all who taught me

PREFACE

Half of this book is about growing up. Our family consisted of four boys I came second and one girl. Our father was a clergyman when the churches were still a most powerful force in the country. Living in what is now called rural and regional Australia, we moved every fourth year to a new district. Even in the smaller towns our life I am surprised to rediscover was intersected by events and people now of national significance.

In the other half of this book I learn to be a historian: I am still learning. I started young, and by the time I was thirty I had written, as a freelance writer, more books on Australian history than probably had any professor of the time. I am talking about quantity, not quality. This book comes to a halt when I reach about the age of forty. I do not end this memoir of my life for any valid reason; I simply thought that I had written enough.

Actually I wrote much of the book at the start of this century. I had the idea that my memory might become weaker, and that therefore it was sensible to write something sooner rather than later. In fact my memory remains fairly tight, or so I believe. Lately I went back to the pages compiled about fifteen years ago and read them again. Occasionally they were erroneous, and so I verified many episodes with the aid of the pocket diary I kept each year and the letters I had carefully saved. Probably errors will remain in this book though I have tried hard to avoid them. Memory, it is said, is not a skilled worker.

I must express my gratitude especially to the team at Penguin Random House my publisher Nikki Christer, editors Rachel Scully and Katie Purvis, and designer Alex Ross. I am also indebted to John Day, the notable Wangaratta gardener, with whom I discuss my books at nearly every stage of the writing, and to my wife Ann and my daughter Anna.

Geoffrey Blainey

March 2019

PART ONE

REMEMBERED IN BLACK AND WHITE

My mother was born in a bark house in East Gippsland in 1903. Her birthplace was called Buchan South, and its hills were so steep and the road so uneven that horses were harnessed to a sledge in order to haul in the supplies. The nearest post office was about 8 kilometres away and the nearest doctor was at least 30 kilometres away; and when our mother was about to be born the doctor was called by telegram. He arrived on horseback to find the baby alive and well. As our grandfather received the small salary of an up-country teacher he could not easily afford the money to pay the doctor for his travelling time.

Hilda May Lanyon, our mother, was the eldest of six children. Most of her very young years were spent in the schoolhouse at Sugar Loaf Creek, a hamlet near Seymour, a station on the SydneyMelbourne railway line. At the age of six she first attended school at Corryong in north-eastern Victoria, not far from the source of the Murray River, and later at Gisborne which was on the railway line between Melbourne and Bendigo. Her last years of schooling were as a scholarship girl at the new Melbourne High School which taught boys too. At this time she lived with an aunt who kept a boarding house in St Kilda, near the bay.

Becoming a trainee teacher, she taught in small schools on the dry northern plains and also was a prize winner at the teachers college. Meanwhile she met my father at a social in the suburban church that her family attended.

My earliest memories are of Mums affection for us, though I hope it is not unfair to add she could be slightly mischievous towards adults who, in her eyes, had lost the right to her affection. Ambitious for her children, she made endless sacrifices to help us. At the same time she encouraged us, to an unusual degree, to become adventurous from an early age. When I was only five she did not worry if I walked far from the small country town where we lived. Though snakes sometimes wriggled across the road on hot days, she ensured as best she could that we were wary of them.

She once held secret literary ambitions, but after her marriage she rarely had the opportunity to pursue them. She enjoyed fluent writing, and loved to read a book for half an hour, though her sense of duty reminded her that she should be washing the clothes or scrubbing the kitchen table. Letters to friends she wrote by the dozen, when she could find the time. Words interested her more than music, especially the classical and religious music that captivated my father. For fine china, fine table linen and the other adornments of domestic life she had a longing but in our house the casualty rate of the china saucers, cups and plates was high, for they were in constant use, serving the numerous people who dropped in to our house for a cup of tea during the course of each week. We have almost forgotten how much a church congregation, particularly Methodists in a country town, formed a fellowship or a kind of tribe, companionable and tightly knit.

Much of my mothers life was spent in the continuous tasks of feeding and clothing and rearing a large family. How hard she worked! She made jam in large quantities, and onion pickles and tomato sauces, along with jars of preserved apricots and plums, so that at the end of the summer her pantry held a few hundred jars and bottles of all shapes and sizes, each carrying a handwritten label signifying that it was chutney or jam and that it was bottled on a certain day. Trays of biscuits were drawn from the oven, and wholesome cakes too. Anything that could be made at home was made there. To save money she bought dozens of eggs when they were cheap and rubbed their shells with a mixture called Keepegg so that they would be relatively edible when winter arrived and fresh eggs rose in price.