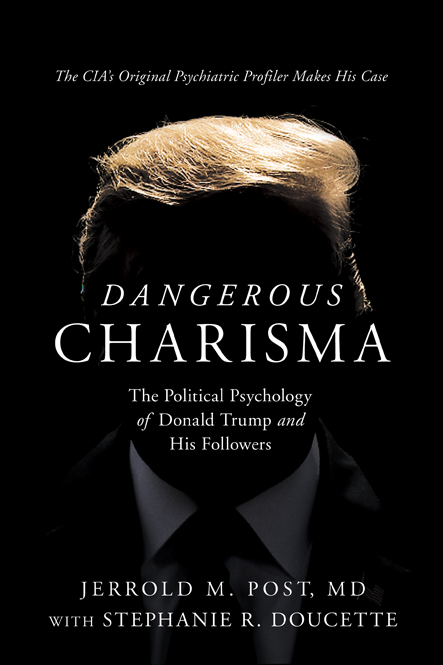

DANGEROUS

CHARISMA

The Political Psychology of

Donald Trump and His Followers

JERROLD M. POST, MD

WITH STEPHANIE R. DOUCETTE

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

To my wonderful wife Carolyn, a full partner in life, who is always there.

And to my three daughters, Cindy, Merrie and Kirsten, of whom I am so proud.

And to my grandchildren, Emily, Rachel, Jack, Sam and Kate, with bright futures ahead.

Jerrold

To my mother and role model, Barbara, who continues to inspire me.

Stephanie

A s the founding father of political personality profiling, I am often asked about the route that took me to my unusual specialty. And like many life decisions, if the truth be known, it was really a matter of serendipity. I had long planned a career in academic psychiatry, and, to my delight, as my two-year research fellowship as a clinical associate at the National Institute of Mental Health was winding down, I had been accepted on the staff at the McLean Hospital, one of Harvard Medical Schools premier psychiatric hospitals. My wife and I were already packing for our move to Belmont, Massachusetts. It was a promising beginning to my academic career.

And then came the call that was to transform my life. Hi, Jerry, this is Herb. After I asked, Herb who?, the caller identified himself as an acquaintance from medical school, someone two years ahead of me, who was really only a passing acquaintance. I hear you dont have a job for next year, Herb saida rather peculiar statement, given I had no idea where Herb had been for the past seven years. Well, actually I do, Herb, but Im always interested in talking, I responded, and we made arrangements to have lunch at a little restaurant in Georgetown, the Hickory Hearth. I remembered little about the restaurant other than that it had interior wooden shutters.

It was a very strange lunch. After about twenty minutes, I realized that Herb knew a great deal about me, which was rather peculiar, since (a) I knew nothing about Herb, (b) Herb was finding out more about me, and (c) he had not said word one about a job. Herb, we were going to discuss a possible job, remember? His teeth tightly clenched so as to prevent lip reading. Herb responded, Id rather not talk about it here. Well, that was kind of weird, I thought. Opening the interior wooden shutters, I sarcastically observed, Look, therere no electronic bugs here. With a tight smile, Herb said, Oh, you like that sort of thing, do you? Oh, sure, I responded. I read all of Ian Flemings James Bond novels in hardcover. Herb smiled mysteriously. Why dont we take a drive, to someplace where we can talk more privately? Follow me in your car. Weird and weirder, I thought, but what the hell, in for a dime, in for a dollar, and I followed Herb, who was driving a beat-up Volvo, over the Key Bridge and onto the George Washington Memorial Parkway, where he pulled into the first parking overlook. Herb got out of his car and started walking toward me, as I got out of my car. Just as we met, a Park Police squad car drove in. Oh, damn, Herb exclaimed, turning red in the face. This happened to me once before. This could be embarrassing. I think wed better drive on.

I got very anxious. What had I gotten myself into? All I could think of was that Herb was unaware that I was happily heterosexual, thank you very much, and he was about to make a homosexual pitch.

But I followed him to the next parking overlook, where Herb got out of his car, I got out of mine, and this time there was no Park Police squad car. After surveilling the area, Herb reached into his blazer pocket and pulled out a folded piece of paper. Before I say anything, I want you to sign this. On official Central Intelligence Agency letterhead, it was labeled Secrecy Agreement. Intrigued, I signed, and Herb tightly smiled. He then declared, rather portentously, Nothing I say can be discussed with anyone. He then proceeded to offer me a position starting a pilot project profiling world leaders at a distance, contingent of course on my getting through the security clearance process.

I obviously had to tell my wife, since we were about to move back to Boston. And I called Steve, my best friend from residency, since I wasnt sure I had the requisite skills for this important position. After all, I hadnt had a single course in international affairs as an undergraduate. Scott reassured me, observing that I was quite good at preliminary psychological profiles based on thin initial evidence, and, then, the clincher, It sounds like a fantastic once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. What have you got to lose? After all, if you dont like it, you can always return to Mother Harvard after a few years.

That convinced me, but first I had to go through the security clearance process. I had sailed through the background security check, as I knew I would. My background was squeaky clean, boringly so. But on the polygraph, I was doing just fine, no drugs, alcoholism, financial problems, no problems with potentially compromising sexual inclinations, until the polygrapher asked me, Have you ever given a classified document to an agent of a foreign power?

Of course not, I had replied indignantly, and the polygrapher, pointing an accusatory finger at me, said, Youre showing a deception response. Fortunately for me, the polygrapher was very experienced, quite sophisticated, and he burst out laughing so hard, he almost had to pull himself off the floor. He knew from my background that I would never have had access to classified documents and would not have known an agent of a foreign power if I stumbled over one. What he finally sorted out with me, after a series of carefully constructed questions, was that after having signed the secrecy agreement and agreeing to speak to no one, having spoken to my wife and my best friend from my psychiatric residency, I had subconsciously treated this as an act of treason, and so had reacted guiltily to the question about classified documents and foreign agents. So much for the infallibility of the lie detector!

And then I began a twenty-one-year career at the CIA, which I can only characterize as a remarkable intellectual odyssey. I had the challenge of developing a method of constructing political personality profiles. Drawing on my undergraduate background in human culture and behavior, I brought together an interdisciplinary team, all at the doctorate level: a cultural anthropologist, a political sociologist, three psychologists with backgrounds in organizational psychology and social psychology, and political scientists with interests in leadership. Several other psychiatrists with an interest in international affairs filled out the team. Each project had a two-man team: a psychologist working with an anthropologist, a psychiatrist working with a political sociologist or a political scientist, etc. I also had the benefit of four consultants from academia with expertise in political psychology, all of whom went through a security clearance. The method we developed insisted upon accurately locating the leader under study in his political, historical, and cultural context. The method and those of several other profilers are described in detail in The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders, a 2003 volume that I edited. Based on the case study method psychiatrists learn in their residency, it consisted of a longitudinal psychobiography coupled with a personality study, only the psychobiographic sketch, rather than emphasizing the life experiences that left the individual vulnerable to mental illness, described the life experiences that shaped the leadership of the political leader.

Next page