Table of Contents

THE GOLDEN BOOK OF THE DUTCH NAVIGATORS

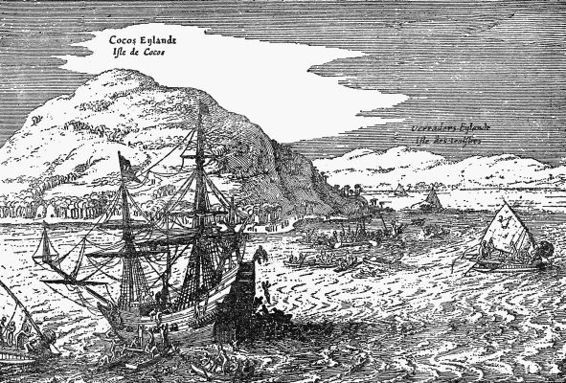

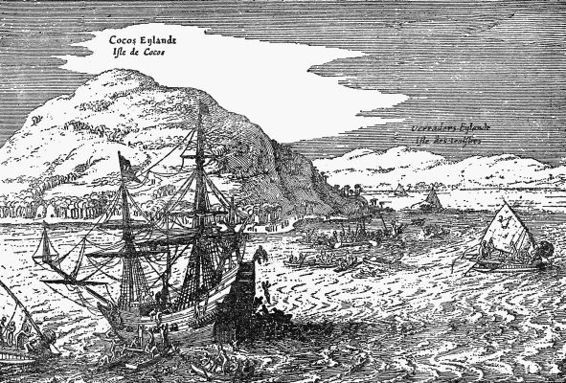

The Cocos Islands

THE GOLDEN BOOK OF THE DUTCH NAVIGATORS

BY HENDRIK WILLEM van LOON

FOR HANSJE AND WILLEM

This is a story of magnificent failures. The men who equipped the expeditions of which I shall tell you the story died in the poorhouse. The men who took part in these voyages sacrificed their lives as cheerfully as they lighted a new pipe or opened a fresh bottle. Some of them were drowned, and some of them died of thirst. A few were frozen to death, and many were killed by the heat of the scorching sun. The bad supplies furnished by lying contractors buried many of them beneath the green cocoanut-trees of distant lands. Others were speared by cannibals and provided a feast for the hungry tribes of the Pacific Islands.

But what of it? It was all in the day's work. These excellent fellows took whatever came, be it good or bad, or indifferent, with perfect grace, and kept on smiling. They kept their powder dry, did whatever their hands found to do, and left the rest to the care of that mysterious Providence who probably knew more about the ultimate good of things than they did.

I want you to know about these men because they were your ancestors. If you have inherited any of their good qualities, make the best of them; they will prove to be worth while. If you have got your share of their bad ones, fight these as hard as you can; for they will lead you a merry chase before you get through.

Whatever you do, remember one lesson: "Keep on smiling."

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

The history of America is the story of the conquest of the West. The history of Holland is the story of the conquest of the sea. The western frontier influenced American life, shaped American thought, and gave America the habits of self-reliance and independence of action which differentiate the people of the great republic from those of other countries.

The wide ocean, the wind-swept highroad of commerce, turned a small mud-bank along the North Sea into a mighty commonwealth and created a civilization of such individual character that it has managed to maintain its personal traits against the aggressions of both time and man.

When we discuss the events of American history we place our scene upon a stage which has an immense background of wide prairie and high mountain. In this vast and dim territory there is always room for another man of force and energy, and society is a rudimentary bond between free and sovereign human beings, unrestricted by any previous tradition or ordinance. Hence we study the accounts of a peculiar race which has grown up under conditions of complete independence and which relies upon its own endeavors to accomplish those things which it has set out to do.

The virtues of the system are as evident as its faults. We know that this development is almost unique in the annals of the human race. We know that it will disappear as soon as the West shall have been entirely conquered. We also know that the habits of mind which have been created during the age of the pioneer will survive the rapidly changing physical conditions by many centuries. For this reason those of us who write American history long after the disappearance of the typical West must still pay due reverence to the influence of the old primitive days when man was his own master and trusted no one but God and his own strong arm.

The history of the Dutch people during the last five centuries shows a very close analogy. The American who did not like his fate at home went "west." The Hollander who decided that he would be happier outside of the town limits of his native city went "to sea," as the expression was. He always had a chance to ship as a cabin-boy, just as his American successor could pull up stakes at a moment's notice to try his luck in the next county. Neither of the two knew exactly what they might find at the end of their voyage of adventure. Good luck, bad luck, middling luck, it made no difference. It meant a change, and most frequently it meant a change for the better. Best of all, even if one had no desire to migrate, but, on the other hand, was quite contented to stay at home and be buried in the family vault of his ancestral estate, he knew at all times that he was free to leave just as soon as the spirit moved him.

Remember this when you read Dutch history. It is an item of grave importance. It was always in the mi nd of the mighty potentate who happened to be the ruler and tax-gatherer of the country. He might not be willing to acknowledge it, he might even deny it in vehement documents of state, but in the end he was obliged to regulate his conduct toward his subj ects with due respect for and reference to their wonderful chance of escape. The Middle Ages had a saying that "city air makes free." In the Low Countries we find a wonderful combination of city air and the salt breezes of the ocean. It created a veritable atmosphere of liberty, and not only the liberty of political activity, but freedom of thought and independence in all the thousand and one different little things which go to make up the complicated machinery of human civilization. Wherever a man went in the country there was the high sky of the coastal region, and there were the canals which would carry his small vessel to the main roads of trade and ultimate prosperity. The sea reached up to his very front door. It supported him in his struggle for a liv ing, and it was his best ally in his fight for independence. Half of his family and friends lived on and by and of the sea. The nautical terms of the forecastle became the language of his land. His house reminded the foreign visitor of a ship's cabin.

And finally his state became a large naval commonwealth, with a number of ship-owners as a board of directors and a foreign policy dictated by the need of the oversea commerce. We do not care to go into the details of this interesting question. It is our purpose to draw attention to this one great and important fact upon which the entire economic, social, intellectual, and artistic structure of Dutch society was based. For this purpose we have reprinted in a short and concise form the work of our earliest pioneers of the ocean. They broke through the narrow bonds of their restricted medieval world. In plain American terms, "They were the first to cross the Alleghanies."

They ushered in the great period of conquest of West and East and South and North. They buil t their empire wherever the water of the ocean would carry them. They laid the foundations for a greatness which centuries of subsequent neglect have not been able to destroy, and which the present generation may triumphantly win back if it is worthy to c ontinue its existence as an independent nation.

CHAPTER I

JAN HUYGEN VAN LINSCHOTEN

It was the year of our Lord 1579, and the eleventh of the glorious revolution of Holland against Spain. Brielle had been taken by a handful of hungry sea-beggars. Haarlem and Naarden had been murdered out by a horde of infuriated Spanish regulars. Alkmaarlittle Alkmaar, hidden behind lakes, canals, open fields with low willows and marsheshad been besieged, had turned the welcome waters of the Zuyder Zee upon the enem y, and had driven the enemy away. Alva, the man of iron who was to destroy this people of butter between his steel gloves, had left the stage of his unsavory operations in disgrace. The butter had dribbled away between his fingers. Another Spanish governo r had appeared. Another failure. Then a third one. Him the climate and the brilliant days of his youth had killed.

But in the heart of Holland, William, of the House of Nassau, heir to the rich princes of Orange, destined to be known as the Silent, the Cunning Onethis same William, broken in health, broken in money, but high of courage, marshaled his forces and, with the despair of a last chance, made ready to clear his adopted country of the hated foreign domination.