Barajima Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

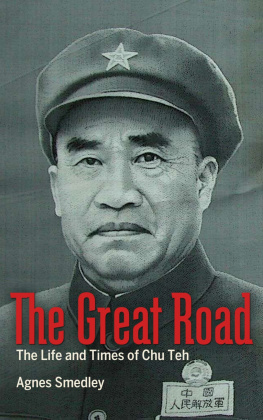

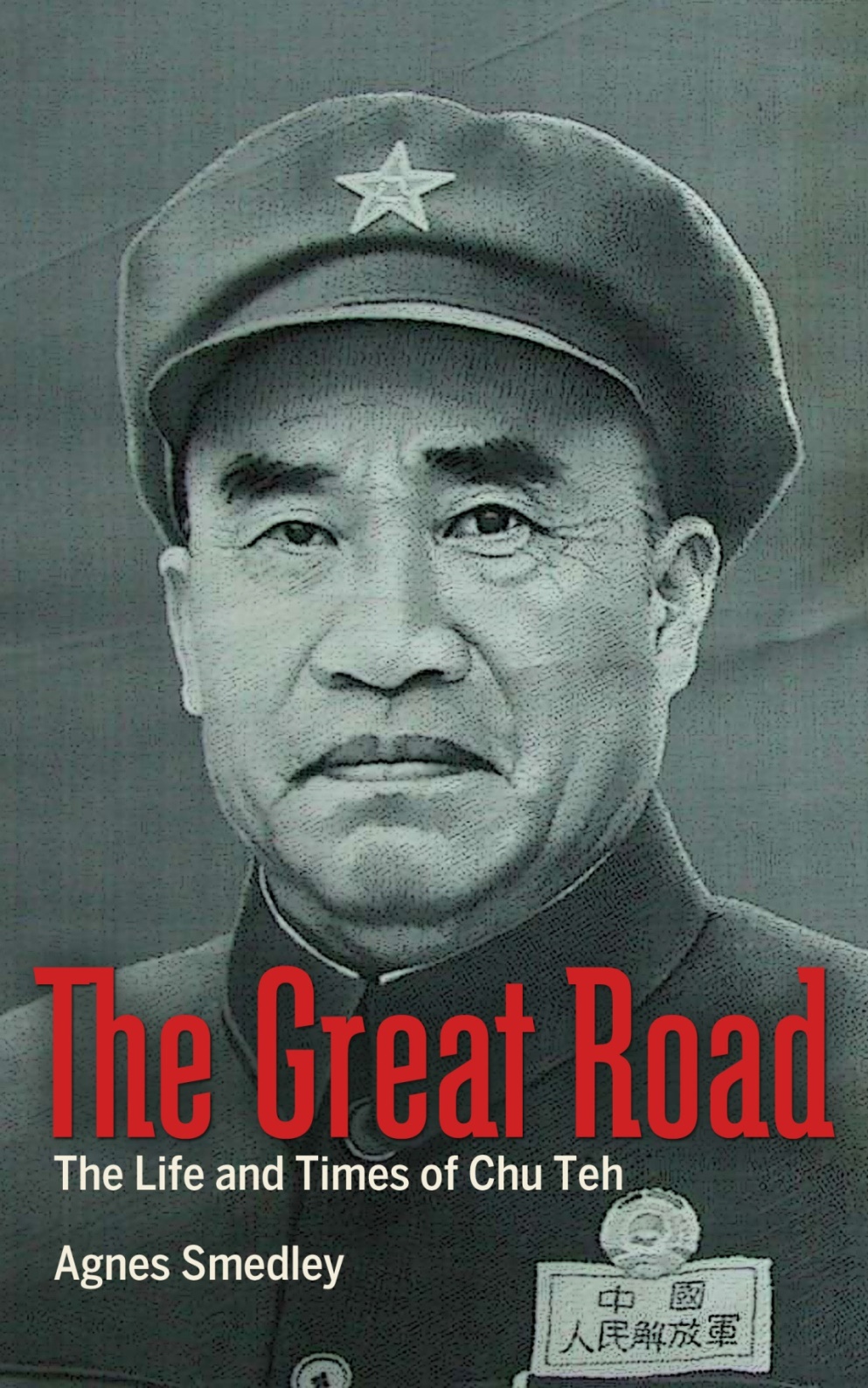

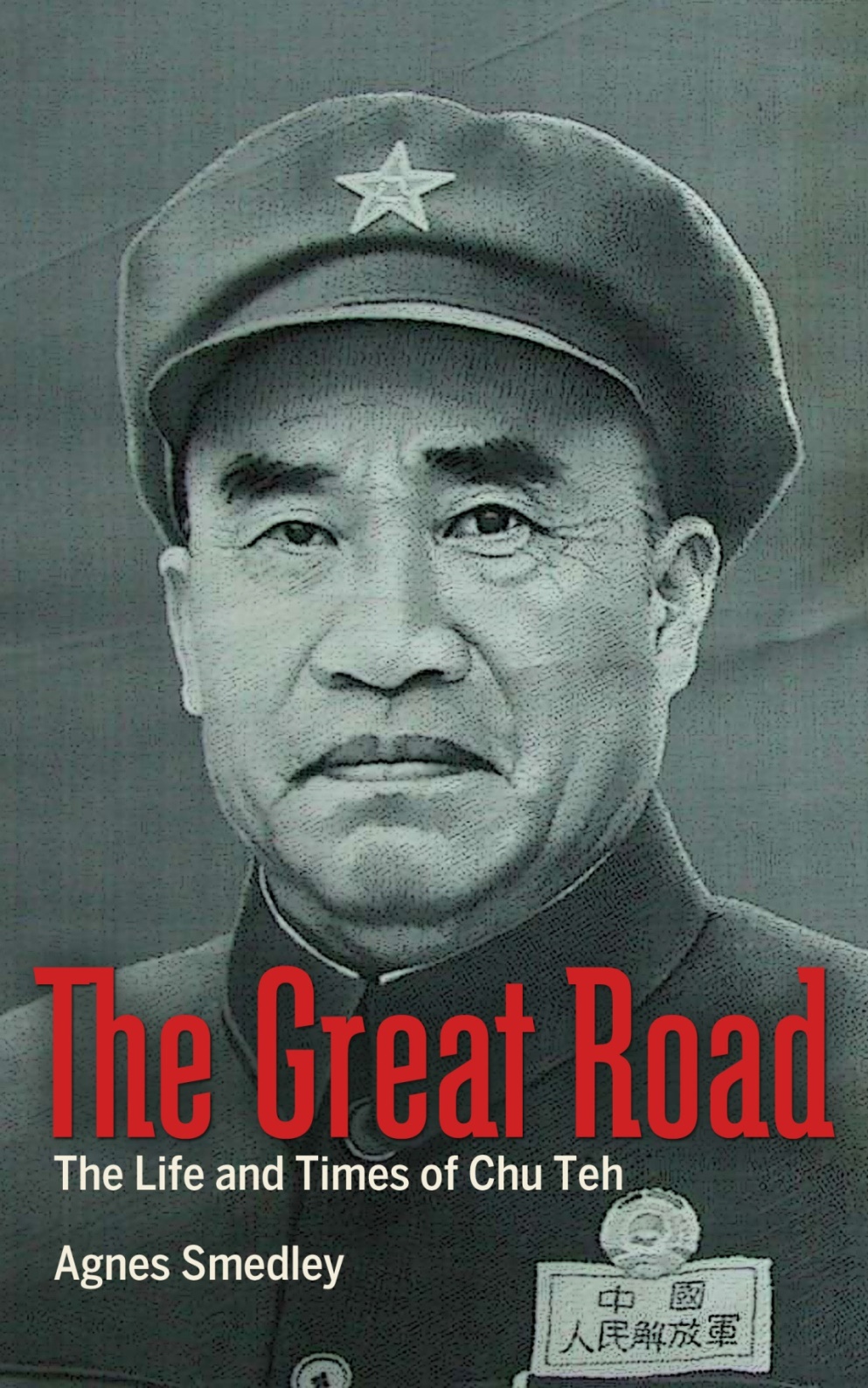

THE GREAT ROAD

The Life and Times of Chu Teh

AGNES SMEDLEY

The Great Road was originally published in 1956 by Monthly Review Press, New York.

Table of Contents

Contents

Publishers Foreword

HISTORIANS of the present are peculiarly fallible. They are circumscribed not only by the unavailability of many facts of varying degrees of relevance but also by the difficulties in the way of achieving a three dimensional stereoscopic view of the facts falling within their field of vision. Yet it is already safe to assert that the Chinese Revolution of 1949 is one of the crucial turning points of the twentieth century, ranking with the October Revolution and the defeat of fascism in World War II in world-historical importance. It has profoundly if not decisively affected the balance of forces between the socialist and non-socialist parts of the world. It has dealt a mortal blow to imperialism in Asia and probably in Africa. It has conclusively shown that a social revolution can be successfully carried through in an economically backward country with only a small modern industrial base and urban proletariat.

Life is richer than any theory, however subtle and complex. The Chinese Communists are Marxists, not Hegelians. When it became clear that the Chinese Revolution could not be contained in the accepted Marxist formulas, they did not say, So much the worse for the Chinese facts. In the midst of their struggle for survival they proceeded to evolve a more flexible and sophisticated theory which enriched Marxism by reflecting and absorbing the stubborn realities of the Chinese scene.

We do not have to await the verdict of future historians to decide that, as far as China was concerned, the Chinese Communists were better Marxists than their foreign mentors, whether Russian, German, French, or Anglo-Saxon. It was one of the paradoxical legacies of imperialism that, because of the prestige attaching to anything foreignincluding foreign revolutionariesin an economically backward country, the Chinese Communist Party had time and again to pay for mistakes for which its foreign advisers were to a considerable, if still undetermined extent responsible. Some of these mistakes, as in the periods immediately preceding the counter-revolutions in Shanghai and Hankow in 1927 and during the Fifth Kuomintang Extermination Campaign in 1933-1934, were almost suicidal in their consequences and entailed great suffering and loss of life. The wheel was to turn full circle, for the Chinese Communists, having thoroughly digested the lessons of the past, showed themselves far less dependent on foreign advice and aid in acquiring power than did the Kuomintang in losing it. There is no need to point the moral for progressives everywhere, whether in the industrially advanced but often politically backward countries or in the colonial and semi-colonial countries still struggling toward national emancipation.

The fallibility of contemporary historians does not reduce their responsibility either to the present generation or to posterity. Like the course of the Chinese Revolution itself, American works on China in the last thirty years have been extremely uneven. It is sad but true that there is still no reasonably comprehensive and dependable book in English on the background and course of the Great Revolution of 1925-1927. Yet the events of those fateful years, in which scores of millions of Chinese began for the first time to take an active part in molding their own lives, are no less fascinating, no less packed with drama and melodrama, no less fraught with historical significance, than the French Revolution from 1789 to 1793. Much Western writing on the subject is dominated by issues often bearing as much on Russian Communist Party history as on China, and its angle of vision tends to suffer from the same kind, if not the same degree, of Europo-centrism as the reminiscences of Old China Hands. For the rest, to this day many Westerners are dependent on Malrauxs Mans Fate for their impressions of the Great Revolution. Whatever its literary meritsand they are no doubt substantial Mans Fate is primarily a story about foreigners in China, or rather in Treaty Port China, and is, moreover, chronologically unreliable. In any case, no conscientious intellectual would want to rely on A Tale of Two Cities or The Gods Are Athirst for his impressions of the French Revolution.

With the 1930s, the record of contemporary historical writing on China began to be much more creditable. A number of Americans have written excellent books either directly on China or with a predominantly China background, although it must be confessed that with one or two exceptions professional historians are not to be found in their ranks and that the stream has been drying up of late. Such outstanding works as Edgar Snows Red Star Over China, Jack Beldens China Shakes the World, The Stilwell Diaries, and Carlsons The Chinese Army the list is not intended to be exhaustiveimmediately come to mind.

Agnes Smedleys works must stand high on any such list. Together they constitute a valuable contribution to the history of the Chinese Revolution. In her own words, she was neither brave nor learned, just historically curious. It says much for her untutored historical curiosity that it was sufficiently strong to enable her to identify herself and grow with the Chinese Revolution.

She has told us something of her own background in Daughter of Earth and Battle Hymn of China. She was born in a north Missouri village in 1893. When she was still quite small, her family moved to a Rockefeller mining camp in Colorado where she acquired a hatred of capitalism with the air she breathed.

She became and remained an aggressive feminist throughout her life. There are few more touching passages in her writings than her description in China Fights Back of her reaction to Chu Tehs refusal to let her go to the Eighth Route Army anti-Japanese battlefront at Wu Tai Shan in the winter of 1937. Evans Carlsons diary gives an independent eyewitness account, which is worth quoting in full:

I told Agnes about my trip to the front, and at dinner tonight at 4 p.m. (our usual hour) Agnes asked Chu Teh for permission to go to Wu Tai Shan with me. Both Chu Teh and Jen Peh-hsi demurred. They offered various excuses, said that those who went to the front had to be prepared to shoot.

Ill shoot! said Agnes. I was raised in the West.

Next page