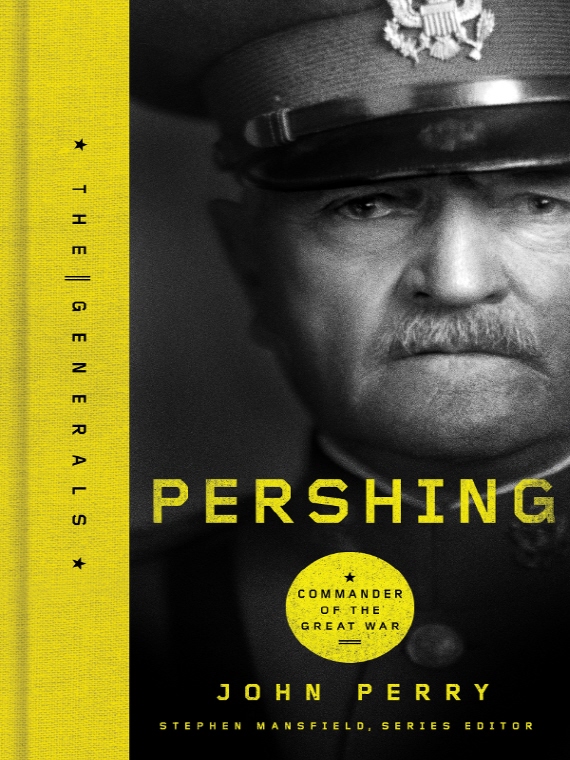

PERSHING

THE | GENERALS

THE | GENERALS

PERSHING

Commander of the Great War

THE | GENERALS

THE | GENERALS

John Perry

2011 by John Perry

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Thomas Nelson. Thomas Nelson is a registered trademark of Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Published in association with the literary agency of Wolgemuth & Associates, Inc.

[If applicable, credits for photography, typesetting, or any other noteworthy vendors]

Thomas Nelson, Inc., titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund-raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail SpecialMarkets@ThomasNelson.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Perry, John, 1952

Pershing : commander of the Great War / John Perry.

p. cm. -- (The generals)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-59555-355-3

1. Pershing, John J. (John Joseph), 1860-1948. 2. United States. Army--Biography. 3.

Generals--United States--Biography. 4. World War, 1914-1918--United States. I. Title.

E181.P516 2011

972.0816092--dc22

[B]

2011015603

Printed in the United States of America

11 12 13 14 15 WOR 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Ivy Scarborough, whose patriotism, strength of character, devotion to duty, and compassion for others make him a man of honor in the Pershing mold, and whose kindness, generosity, and encouragement make him a precious friend.

Contents

TO CONTEMPLATE THE lives of Americas generals is to behold both the best of us as a nation and the lesser angels of human nature, to bask in genius and to be repulsed by arrogance and folly. It is these dichotomies that have defined the widely differing attitudes toward the man on horseback, which have alternatively shaped the eras of our national memory. We have had our seasons of hagiography, in which our commanders can do no wrong and in which they are presented to the young, in particular, as unerring examples of nobility and manhood. We have had our revisionist seasons, in which all power corrupts military power in particularand in which the general is a reviled symbol of societal ills.

Fortunately, we have matured. We have left our adolescence with its gushing extremes and have come to a more temperate view. Now, we are capable as a nation of celebrating Washingtons gifts to us while admitting that he was not always a gifted tactician in the field. We can honor Pattons battlefield genius and decry the deformities of soul that diminished him. We can learn both from MacArthur at Inchon and from MacArthur at Wake Island.

We can also move beyond the mythologies of film and leaden textbook to know the vital humanity and the agonizing conflicts, to find a literary experience of war that puts the smell of boot leather and canvas in the nostrils and both the horror and the glory of battle in the heart. This will endear our nations generals to us and help us learn the lessons they have to teach. Of this we are in desperate need, for they offer lessons of manhood in an age of androgyny, of courage in an age of terror, of prescience in an age of myopia, and of self-mastery in an age of sloth. To know their story and their meaning, then, is the goal here, in the hope that we will emerge from the experience a more learned, perhaps more gallant, and, certainly, more grateful people.

Stephen Mansfield

Series Editor, The Generals

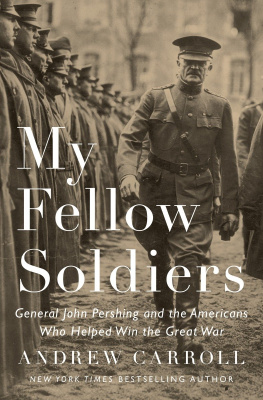

NO OTHER AMERICAN military leader is as important and yet as little known as John J. Pershing. He led an army of more than a million men in France, defeating the seemingly invincible German war machine after only six months of offensive action. Russia had crumbled into anarchy; Britain and France had fallen on their knees after three years of horrific fighting. Pershing crossed the Atlantic determined to do battle a different way. To carry out his plan, he had to fight a political war with his allies. They insisted on continuing as before. Seeing the failure of their approach, Pershing refused.

When the French general-in-chief relieved him of command, Pershing ignored the order and went on to stop the Germans forty-five miles from Paris, saving a nation and probably a continent. By the time he sailed home, Pershing had become the only U.S. army officer in history to be commissioned General of the Armies during his lifetime. The one other soldier so honored, a century and a half after his death, was George Washington.

It was Pershing, more than anyone else, who brought the American army into the modern era. He saw the power of twentieth-century weapons for the first time as an observer during the Russo-Japanese War. The machine gun and other innovations used in that war changed warfare forever. Pershing was a keen observer, a lifelong student and teacher. What he learned in Manchuria, he taught in Mexico more than a decade later when President Wilson sent him to retaliate against Pancho Villa. For the first time, American divisions fought using radios and air support. During World War I, Pershing and his tactical genius aide, George C. Marshall, executed the first battle in American history to coordinate infantry, artillery, tanks, and air support. Troops were armed with machine guns, hand grenades, and poison gas. Draft horses shared the miserable roads with motorized trucks and the generals limousine, the latter fitted with double rear wheels to negotiate the mud.

Pershing returned to the United States a hero. There was a ticker tape parade in New York, an address to a joint session of Congress, rumors of a presidential bid, gossip about the society women the handsome widower was dating, and a Pulitzer Prize for his history of the war to end all war.

And yet today General Pershing has faded away to the second or third tier of Americas historical consciousness. While some of us have heard the name, many more have not. His accomplishments rightly place him in the company of great generals such as MacArthur, Eisenhower, and Patton, all of whom he commanded and inspired, and all of whom he outranked. He shaped world events in Europe as surely as Woodrow Wilson or David Lloyd George. Had they listened to him about forcing Germany into unconditional surrender, his influence would have been even greater. He served with Theodore Roosevelt in CubaPershing was at San Juan Hilland headed the American Expeditionary Force when one of its junior officers was a captain from Missouri named Harry Truman. Still, for all that, Pershings light has dimmed with time while Roosevelts and Trumans have not.

Part of the reasona large part, some would claimis that, as a public figure, John J. Pershing was not a lovable man. Roosevelt (both of them), Truman, Churchill, de Gaulle, and other contemporaries were seen as compassionate, dedicated, inspiring, and personable figures. Yes, FDR was elitist, Truman coarse with his language, de Gaulle conceited (he once declared, I am France), and all great men have their shortcomings. But these were people the public would gladly invite to dinner.

Next page

THE | GENERALS

THE | GENERALS