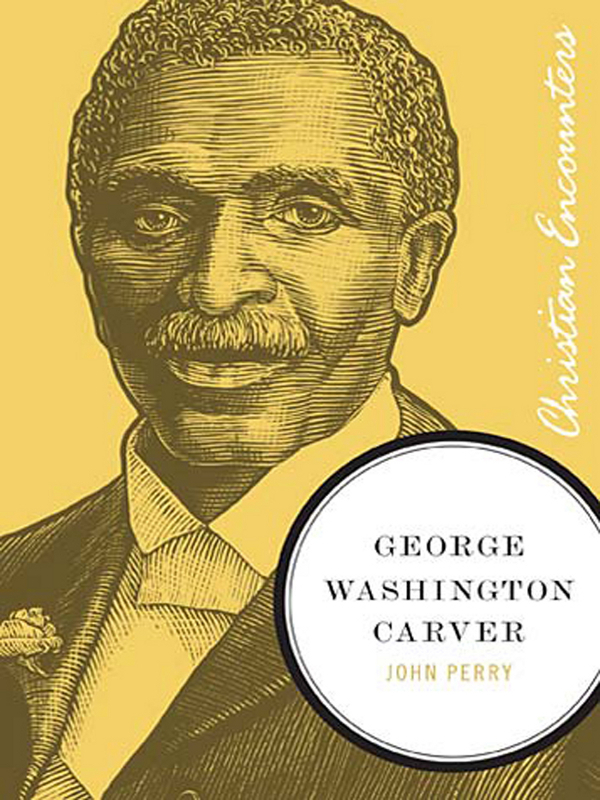

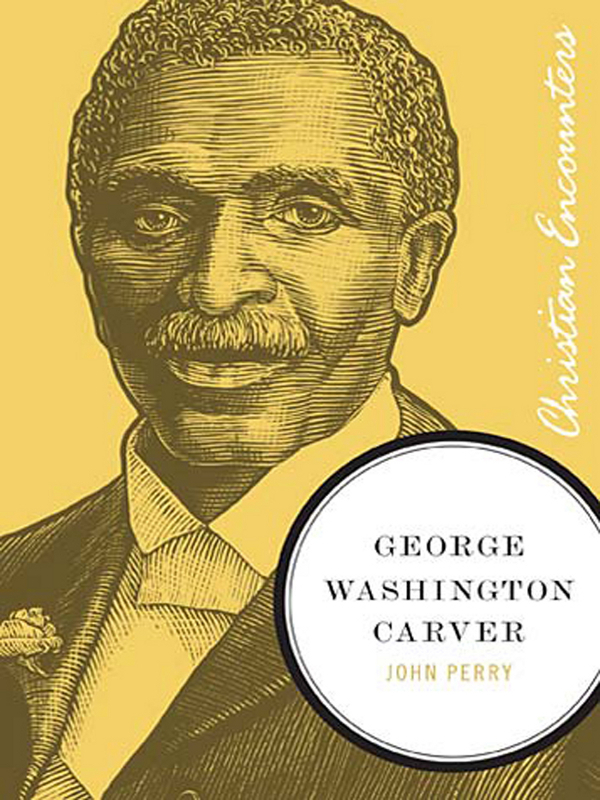

CHRISTIAN ENCOUNTERS

GEORGE

WASHINGTON

CARVER

CHRISTIAN ENCOUNTERS SERIES

GEORGE

WASHINGTON

CARVER

JOHN PERRY

2011 by John Perry

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee. Thomas Nelson is a trademark of Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Thomas Nelson, Inc., titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund-raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail SpecialMarkets@ThomasNelson.com.

Published in association with the literary agency of Wolgemuth & Associates, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Perry, John, 1952

George Washington Carver / John Perry.

p. cm. -- (Christian encounters series)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-59555-026-2

1. Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943. 2. African American agriculturists--Biography. 3. Agriculturists--United States--Biography. I. Title.

S417.C3P37 2011

630.92--dc22

[B]

2011006173

Printed in the United States of America

11 12 13 14 15 HCI 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my brother, Scott,

whose kindness and gentleness

are part of what makes him

such an inspiring husband,

father, brother, and friend.

CONTENTS

1

CARVERS GEORGE

S outhwestern Missouri in the winter of 1863 was a lawless and deadly land. The war that ripped the United States in two had divided Missouri families against themselves. Though a slaveholding state, the legislature had voted in 1861 to stand with the Union even as Confederate sympathies ran strong. Governor Claiborne Jackson himself led an army of secessionist irregulars on one bloody raid after another. The southwest corner of the state in particular endured endless skirmishes as the two sides fought for control. Making a bad situation worse, the region was a crossroads for soldiers, militiamen, marauders, scavengers, opportunists, bounty hunters, and deserters traveling between the Union and the Confederacy, some with shifting loyalties, others who willingly took the law into their own hands. From rebel Arkansas to the south, raiders came to capture escaped slaves and return them for a reward. Abolitionists rode in from Kansas to the west, once a slave-holding territory and now a free state with its own bloody history, to help Missouri defend itself against homegrown adversaries. In between Arkansas and Kansas, the Oklahoma Indian Territory offered vast empty spaces to hide vigilante patrols, recruit soldiers for both sides, and for runaway slaves to disappear into the trackless plains.

Marion Township, just outside Diamond Grove near the Newton County seat of Neosho, was a rural settlement in the thickest of the Missouri guerrilla fighting. Confederates took over the county government and adopted an ordinance of secession, though in Neosho the Union loyalists likely outnumbered Southern sympathizers. Raiders and looters galloped through the countryside day and night, as did ordinary criminals who found opportunity in the confusion and lawlessness of the moment.

One of the five slaveholders listed in the Marion Township census of 1860 was Moses Carver. He and his wife, Susan, were relatively prosperous farmers, though they lived modestly and seemed to have no material wealth beyond what their neighbors did. Carver was also a successful stock trader and horse trainer. The couple had no children, which was a liability because farmers needed children to keep a place in good order; tending crops, cultivating a kitchen garden, caring for livestock, repairing fences and gates, cutting firewood, drawing water, and maintaining equipment was more than a couple alone could do. Like many Americans before him, Moses Carver was against the idea of one human being owning another but saw slavery as an economic necessity. The 1860 census listed Carver as owning two slaves, a woman named Mary and her mulatto (half white) infant son, Jim, born the previous October. Carver had bought Mary for seven hundred dollars in 1855 when she was thirteen. A female slaves children became the property of her owner.

By late 1863 Mary had another son, George. As with most children born in the countryside, especially slaves, there was no record of his birth. In later years George said he had been born in 1864 or 65. It is possible that a baby recorded as born in Marion Township on July 12, 1860, was George. A birth date so soon after his brothers indicated he arrived prematurely. That would account for his being small, frail, and hampered by severe breathing problemsconditions associated with premature birth, and which he dealt with all his life. George never knew his father, who died either before he was born or about that time. Again no official accounts exist, though in describing his early years, George wrote in 1922 that his father was the property of Mr. Grant, owner of the plantation next door, and was killed soon after George was born while hauling wood with an ox team. In some way he fell from the load, under the wagon, both wheels passing over him.

Mary and her boys lived in what had once been Moses and Susans cabin, a one-room log building with a fireplace, one window opening with shutters but no glass (a rare and expensive luxury on the frontier), and a packed earth floor. Earlier the Carvers had shared it with Moses brothers three children, two boys and a girl, whom they raised after their father died. The children were grown and gone by 1860, and at some point the Carvers built a similar but larger home for themselves and gave their old home to Mary and her boys.

Some slaveholders in southwestern Missouri abandoned their homesteads during the war in the face of threats, raids, and destruction, but Moses would not be frightened off his property. After decades of work, he had built one of the most valuable farms in town, with a hundred acres under cultivation, an orchard, beehives, and a range of livestock. Though others might buckle under the pressure, Moses Carver was a stubborn man when he believed he was right.

Stories vary as to how many times the Carver farm was raided. There is one account that robbers came demanding money, which Carver refused. They ordered him to reveal where his savings were hidden. When he still said nothing, they hung him by his thumbs and burned his feet with hot coals. Stubborn Moses remained silent until the raiders finally gave up.

Either then or during another raid, invaders made off with property far more valuable to the Carvers than buried cash. One bitter cold November day Moses was working in the field and had Jim with him, while Mary was in her cabin with George. Seeing the attackers ride up, Moses and Jim hid from them, but Mary and George were kidnapped.

The men may have been traders or bounty hunters planning to sell captured slaves in Arkansas. As soon as they left, Moses started planning to rescue Mary and her boy, but he had no idea where to look first. His neighbor, Sergeant John Bentley, was a Union scout who knew the shadowy world of bushwhackers and vigilantes in the region and agreed to help. Moses promised a racehorse and forty acres of land for the return of his property. Riding through the night, Sergeant Bentley and his search party found George alone in an abandoned cabin. Bentley instructed the others to continue the chase, then carried the boy home and laid him in the crib with his own son for the night. The next day Bentley returned George to the Carvers and reported there was no sign of Mary. Georges mother was never heard from again. Since the sergeant had found one slave but not the other, Moses gave him part of the reward: a fine horse valued at three hundred dollars.

Next page