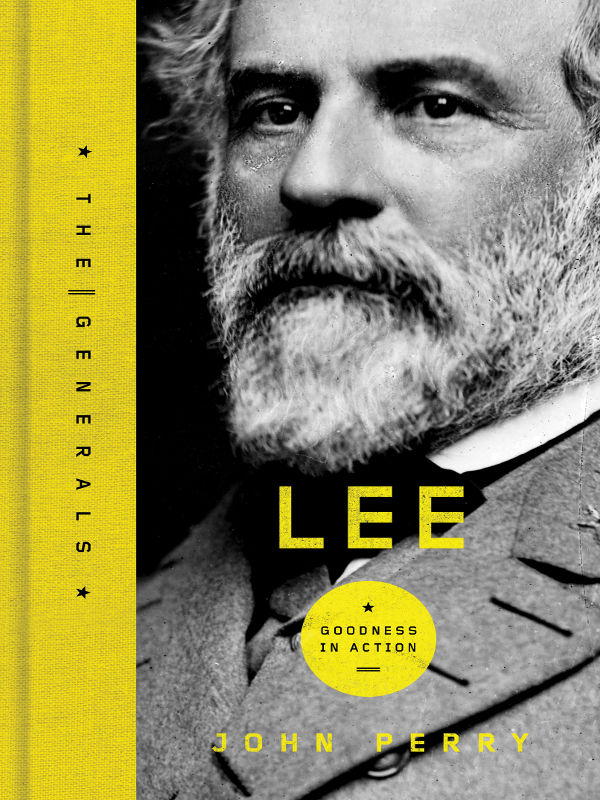

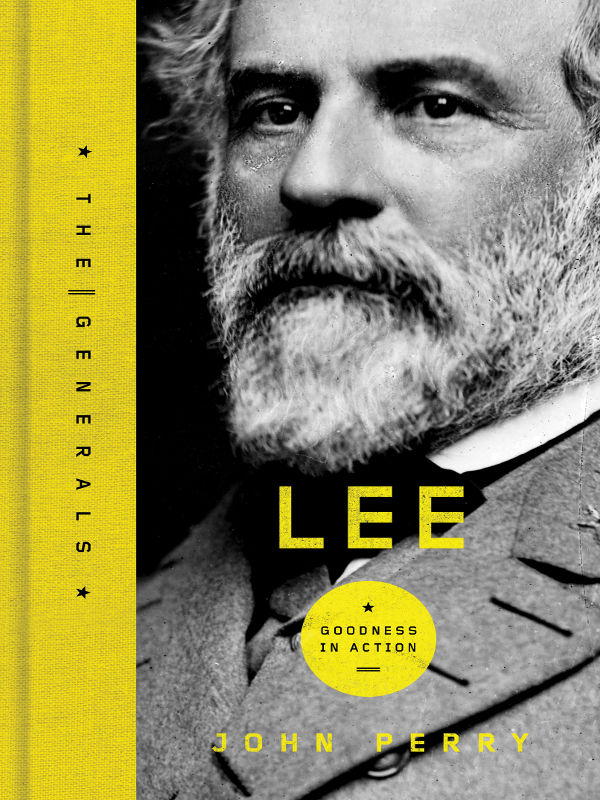

LEE

THE | GENERALS

THE | GENERALS

LEE

A Life of Virtue

THE | GENERALS

THE | GENERALS

John Perry

2010 by John Perry

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Thomas Nelson. Thomas Nelson is a registered trademark of Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Thomas Nelson, Inc., titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund-raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail SpecialMarkets@ThomasNelson.com.

Scripture quotations are from the King James Version.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Perry, John, 1952

Lee : virtue in action / John Perry.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-59555-028-6

1. Lee, Robert E. (Robert Edward), 18071870. 2. GeneralsConfederate States of AmericaBiography. 3. Confederate States of America. ArmyBiography. I. Title.

E467.1.L4P47 2010

973.7'3092dc22

[B]

2010016322

Printed in the United States of America

10 11 12 13 14 WRZ 5 4 3 2 1

To Robert Thomison, for forty years a

true and faithful friend, and a Southern

gentleman who has held fast to the best of the

old while embracing the best of the new

Contents

TO CONTEMPLATE THE lives of Americas generals is to behold both the best of us as a nation and the lesser angels of human nature, to bask in genius and to be repulsed by arrogance and folly. It is these dichotomies that have defined the widely differing attitudes toward the man on horseback, which have alternatively shaped the eras of our national memory. We have had our seasons of hagiography, in which our commanders can do no wrong and in which they are presented to the young, in particular, as unerring examples of nobility and manhood. We have had our revisionist seasons, in which all power corrupts military power in particularand in which the general is a reviled symbol of societal ills.

Fortunately, we have matured. We have left our adolescence with its gushing extremes and have come to a more temperate view. Now, we are capable as a nation of celebrating Washingtons gifts to us while admitting that he was not always a gifted tactician in the field. We can honor Pattons battlefield genius and decry the deformities of soul which diminished him. We can learn both from MacArthur at Inchon and from MacArthur at Wake Island.

We can also move beyond the mythologies of film and leaden textbook to know the vital humanity and the agonizing conflicts, to find a literary experience of war which puts the smell of boot leather and canvas in the nostrils and both the horror and the glory of battle in the heart. This will endear our nations generals to us and help us learn the lessons they have to teach. Of this we are in desperate need, for they offer lessons of manhood in an age of androgyny, of courage in an age of terror, of prescience in an age of myopia, and of self-mastery in an age of sloth. To know their story and their meaning, then, is the goal here and in the hope that we will emerge from the experience a more learned, perhaps more gallant, and, certainly, more grateful people.

Stephen Mansfield

Series Editor, The Generals

ROBERT E. LEE has been one of the most misunderstood figures in American history for a hundred and fifty years. Who he was and what he stood for are still controversial because the scars of the Civil War remain tender six generations after the last shot was fired. We even argue today over whether to call it the Civil War (implying a nation divided) or the War between the States (meaning two nations). Questions linger over so basic a point as what the fighting was all about. Why did Americans shed one anothers blood so savagely for four terrible years? Why did we fight the deadliest war in our history on our own soil against our own brothers? The typical history textbook will tell you that it was all about slavery. Yet the same source omits the facts that President Lincoln campaigned on a platform of not interfering with slavery anywhere it was already legal, that not all slave states joined the Confederacy, and that only about 10 percent of the white population in the South actually owned slaves.

These books, and the generations of Americans whove read them, will say that Robert E. Lee fought to preserve slavery. During his lifetime and today, Lee has been accused of defending the indefensible, of going to war to uphold laws that allowed one man to own another the same way he might own a chair or a set of dishes. He appears to be a wealthy slave master who turned against his own nation to defend the rich and leisurely lifestyle of the Virginia plantation class, which depended on slave labor.

Northern newspapers branded Lee as a traitorous lowlife who was following in the footsteps of Benedict Arnold, the notorious Revolutionary War turncoat. Lee never denied these slurs that sprang up early in the war and follow him to the present day. He never fought back against his slanderers because he was too busy fighting on the battlefield. Besides, he was such a humble man he wouldnt have done it anyway. And since he never tried to shape his own historical legacy, his enemies shaped it for him, tarring him down through the years with the brush of slaveholder and turncoat.

The truth about Robert E. Lee, gleaned from his own words and the events of his life, is exactly the opposite. Lee consistently condemned slavery as unnatural, ungodly, impractical, economically flawed, and wrong. He probably never owned a slave in his life. Based on the sketchy documentation that survives, he may have inherited four slaves from his mothers estate, but evidently he gave them their freedom within a month. His wife inherited nearly two hundred slaves when her father died, but they were all freed within five years, as her father had directed in his will. By the time Lincolns government enacted the Emancipation Proclamation on New Years Day 1863, there were no slaves left on the Lee family property to be freed by it. Following the spirit of the law as well as the letter, Lee tracked down as many runaway slaves as he could and had their letters of manumission delivered to them.

Lee believed without question that slavery was a moral outrage. Yet like most Southerners who shared his view, he accepted the institution because he didnt know how to deal with the practical obstacles to emancipation. How would millions of blacks with no education and no property mix with a white society that had held them in bondage for more than two hundred years? Would they flood the labor market and drive down wages, causing an employment crisis for better-paid white workers? Would centuries of pent-up resentment explode into a slave revolt? Lee believed that the problems of institutionalized slavery would be solved, and that slavery would eventually be phased out in Gods good time. He was confident that the abolitionists would reach their goal by being patient and practical a lot sooner than they would by forcing proclamations and ultimatums down Southern throats. Lee categorically and repeatedly condemned slavery. He never endorsed it and never fought for it.

Next page

THE | GENERALS

THE | GENERALS