This Is a Borzoi Book

Published by Alfred A. Knopf

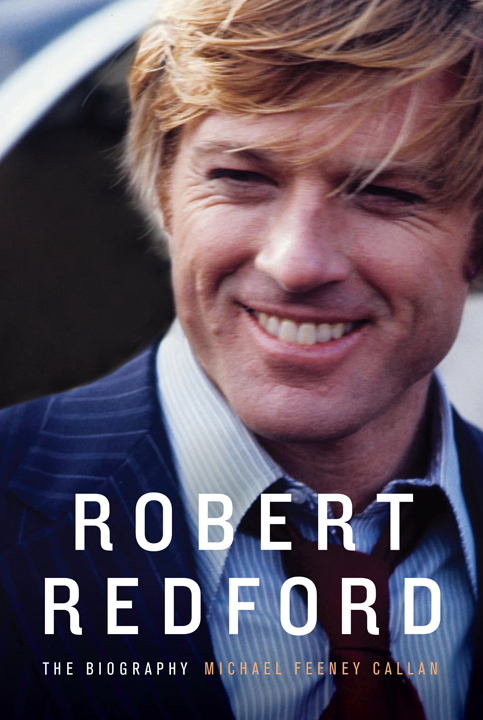

Copyright 2011 by Michael Feeney Callan

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Portions of this work were previously published in Vanity Fair.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Callan, Michael Feeney.

Robert Redford : the biography / Michael Feeney Callan.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-0-307-27297-3

1. Redford, Robert. 2. Motion picture actors and actresses

United StatesBiography. I . Title.

PN2287.R283C35 2009 791.43028092dc22 [ B ] 2009019300

Jacket photograph Estate of Stanley Tretick

Jacket design by Jason Booher

v3.1

To

Corey, Paris and Ree

with love and thanks

true journey-work of the stars

What is become of the horseman, the cow-puncher, the last romantic figure upon our soil? For he was romantic. Whatever he did, he did with his might. The bread that he earned was earned hard, the wages that he squandered were squandered hard. Well, he will be here among us always, invisible, waiting his chance to live and play as he would like. His wild kind has been among us always, since the beginning: a young man with his temptations, a hero without wings.

Owen Wister, The Virginian

Contents

Introduction

America Is the Girl

Rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! the solid earth! the actual world! the common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? where are we?

Henry David Thoreau, The Maine Woods

Its Brigadoon, really, on a summers day. You drive an hour south out of Salt Lake City on the I-15, turn east at the signposts for the Uinta National Park and catch the Provo Canyon Road as it wends along a river once famous for trout as populous as cobblestones. Then you head north again along the Alpine Loop road, and in a vee of aspens you find it: a modest trunk road to a circle of timber cabins, a ski lift or two beyond, and above, the breathtaking elegance of the glacial Mount Timpanogos, towering almost twelve thousand feet above sea level. Apart from the few small-signage properties, and the spidery frames of the lifts, its as it was two centuries before, when the Ute Indians lived here. It is still the home of ground squirrels and four types of snakes. Golden eagles still overfly it. Mountain lions have been sighted. Deer numbered in the thousands until the particularly ferocious winter of 1990 wiped out 90 percent of them. Now the elk are back in numbers. It possesses, it seems, some powerful organic mechanism of renewal.

When you step out of your car (the only way to get here), the air has the minty intensity of the Alps. You breathe deeply, because at this elevationmore than six thousand feetthe air is thinner. Visitors get nosebleeds. It seems a place of enormousness. Huge sky. Huge mountains. Huge contradictions. Henry David Thoreau got lost on Mount Katahdin and in The Maine Woods expressed both the beauty and the concurrent threat of nature. Its a place to take pause.

Robert Redford discovered this canyon more than fifty years ago. Originally it was squatters land, purchased from the government by a Scottish family in 1900 for $1.25 an acre under the terms of the 1877 Desert Land Act and granddaddied for sheep farming thereafter. By the 1950s the wool market was dead and the lands all but derelict. In 1961 Redford and his wife bought two acres and built a home. In 1968, flush with Hollywood success, he purchased several thousand adjoining acres and later called it Sundance in recognition of his movie breakthrough. In 1980 he set up an arts colony to promote young filmmakers. Id seen small movies like Heartland [directed by Richard Pearce], and saw passion that was going nowhere. There was no infrastructure to support these films. Hollywood in the seventies was only interested in blockbusters. His remedy was an arts commune, based in part on the artists colony Yaddo and on the theory of the assembly line that would address scriptwriting, script filming and, eventually, product selling. He asked friends like actor Karl Malden, writer Waldo Salt and cinematographer Lszl Kovcs to assist. They came to the canyon and set the wheels in motion. Seventeen new filmmakers were invited that first season, and the results were immediate. Enthusiasm was defined by the work ethic; people labored seventeen hours a day. Short movies were shot, edited, debated, reshot, finessed. Aspirant filmmakers who came with nothing more than an idea left with the bones of a professional screenplay. A few thousand dollars were spent that first summer. Within two years the sponsors were rolling in and millions were being directed toward what was essentially an alternative filmmaking industry. In popular perception, Robert Redford had invented independent cinema.

Redfords initiative came on the heels of a stream of eco-activism and Indian rights pursuits. Its principle, says Redford, was conciliatory. He recognized the importance of business in Hollywood as much as he recognized the frustration of the independents. But a sense of exclusion, he felt, repressed emerging talent. Apropos of his environmental activism, he wrote in the Harvard Business Review that people need the chance to see how much agreement is possible. Fostering independents, he felt, could only enhance Hollywood. But there were inherent contradictions. He disliked the overintrusion of Hollywood and only reluctantly allowed a studio presence in the Sundance boardroom. He wanted a clear demarcation zone. The bullishness raised hackles. Journalists visited and observed his brand of altruism as suspect. There was about it, one wrote, indulgence. The rebellious seventies had made him a star and a wealthy man: This rustic Xanadu and the ideals behind [it] are his way of keeping that decade alive in all its skepticism and sincerity. Some accused him of granola filmmaking. But Redford stood his ground with ferocity, even against the advice of his lawyers when they told him he couldnt afford the mortgages and overheads that amounted to several hundred thousand dollars a year.

Redford maneuvered to keep his vision alive. He had in place already a mom-and-pop ski resort that comprised a ski lift and a basic restaurant. In 1985 he commercialized the operation, endorsing an expansion plan for accommodations around the estate that included two multiunit condominiums and a hundred houses, all of which, in keeping with his passion for maximum conservation, were built below the tree line. In 1989 he introduced a trading catalog, selling western apparel. Combined, these enterprises effectively underwrote the arts labs. But the labs, he felt, needed an evolutionary nudge. Filmmakers were being trained and projects honed, but there was nowhere for these projects to be seen. The showcasing required a festival forum, and he had it on his doorstep with the Salt Lake Citybased United States Film and Video Festival. In 1985, he annexed it and relocated it in Park City, thirty miles up the road. Henceforth, the Sundance lab projects were one step closer to Hollywood.

In 1989, the film festival liberated Sundance. One movieSteven Soderberghs