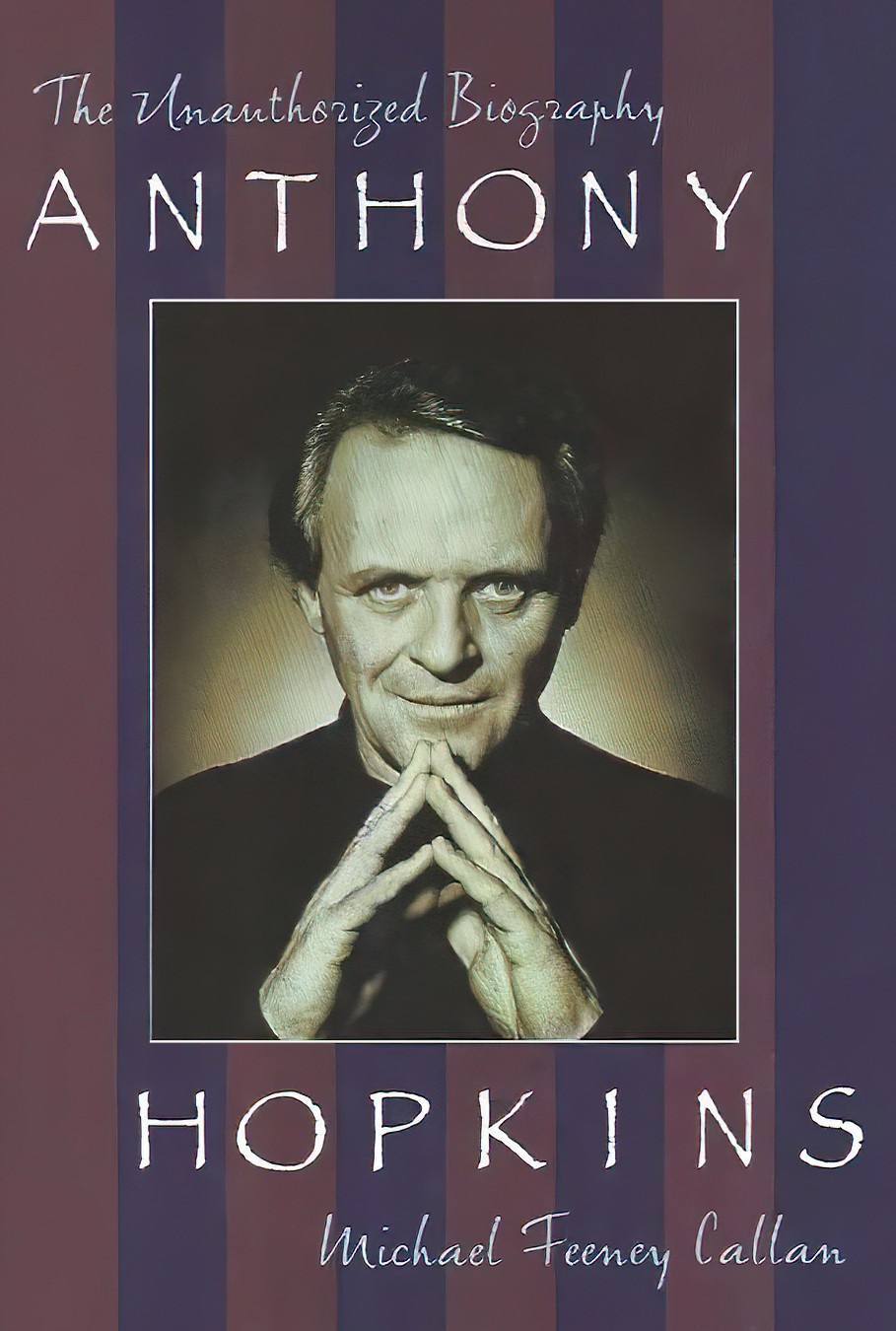

ANTHONY

HOPKINS

The Unauthorized Biograph y

Michael Feeny Callan

Charles Scribners Sons

New York

Maxwell Macmillian International

New York Oxford Sydney

Copyright 19513 by Michael Feeney Callan First United States Edition 1994

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Charles Scribners Sons Macmillan Publishing Company 866 Third Avenue

New York, NY 10022

Macmillan Publishing Company is part of the Maxwell Communication Group of Companies.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Callan, Michael Feeney.

Anthony Hopkins: a biography/ Michael Feeney Callan.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-684-19679-4

1. Hopkins, Anthony, 1937- 2. Actors-Great Britain- Biography I. Title.

PN2598.H66C36 1994

792.028092-dc20 93-40256 CIP [B]

Macmillan books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases for sales promotions, premiums, fund-raising, or educational use.

For details, contact:

Special Sales Director Macmillan Publishing Company 866 Third Avenue

New York, NY 10022

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

For Paris, ma belle

CONTENTS

I love going back to the past to look around. I dont know what the hell Im looking for.

Anthony Hopkins, February 1993

Innocence sometimes invites its own calamity

I Ching

INTRODUCTION

AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Sir Anthony Hopkins offered me little comfort as I progressed with this work. After tenuous contact, which predated his 1992 Oscar and subsequent knighthood, he finally wrote that he had had enough of talking about yours truly and, without much sympathy it seemed, I was on my own. Shortly after, as the routine of writing hit full flight, his wife Jenni, a former film production assistant who acts persuasively as his personal secretary, contacted my chief researcher Karen Cook to complain of our pursuit of Muriel, Hopkins mother, who lives in comfortable retirement at Caldicott, Gwent, just a few miles from the stomping ground of the actors youth. She requested that we desist from pursuing an interview and burn Mrs. Hopkins phone number. She made it clear that Muriel Hopkins was elderly, that her memories had no substantial bearing on the story we had to tell, and that she was not in the best of health. We, of course, desisted. Anthony Hopkins had earlier emphasized that he would put up no obstacles for me, but at the same time that he would like to shield whatever close friends I have from the interrogation of biographical analysis.

To be honest, his concluding position suited me. Aware as I was of his 1989 authorized biography, Quentin Falks very readable Too Good to Waste, I was wary of the inevitability of restrictions that would come with any formal participation. The deal struck with Falk in the late eighties prevented any investigation of Hopkins first marriage, to comedian Eric Barkers daughter Petronella, an actress he met in Wales and grew dose to during their contract period at the National Theatre, and who shared with him the storm of his early alcoholism. It also restricted analysis of the alcoholism itself, I believe, in a subtle censorship. Though Hopkins is on record admitting to fifteen years of alcohol abuse, Falks book offers a bald graph of that illness and only a one-page reference to Alcoholics Anonymous in the index.

The issue of a subjects participation in or authorization of a biography has always challenged the careful reader. While it is generally accepted that strict autobiography carries the mandate to hedge and exonerate, approved biographies can be fishy stuff too. Humphrey Barton, biographer of Benjamin Britten and others, illuminated the problem when he wrote in The Times. I recall, while writing one biography, standing late at night outside my subjects house long after he had died and everyone departed and saying to myself, If only I could tell readers what really happened It did not amount to much, I suppose; chiefly a great deal more domestic misery than I had been able to portray, for fear of family censorship. But I felt, and still feel, as if the real story had been omitted from the book.

For my money, the paragon autobiographies are those of Bertrand Russell (where he admits to failings of love on account of his dental pyorrhoea) and H. G. Wellss Experiment in Autobiography (where he cheerfully admits to a penchant for infidelities in his seventies). These deploy a bare-faced candour as enriching for its prejudice and pomposity as it is for its deeply significant integrity. Few comparable authorized works jump to mind. Most if not all in the realm of showbiz seem compromised by the vested interest. Certainly, in the narcissistic mythology of showbiz, the very principle of revelatory honesty seems inapt. The ego is all, so living players reinforce the goods at every turn. Superior intellects only heighten the game. Chaplins memoir is a titanic work of damage control, Gielguds plain slippery. Lesser stars with lesser visions parlay work that diminishes the triumph of the printing press and makes fools of us all.

Increasingly, as a result of my own previous biographies Sean Connery gave me the silent nod, then kept his distance; Richard Harris authorized me, then withdrew when I deviated from his chosen path of suitable interviewees I have come to believe that the only valid kick-off point in a biographical study is fair distance. The honest biographer is then presented with the disarrayed carpet of circumstantial evidence, and forced to make up his own mind.

Biography at its best is detection. In the case of Tony Hopkins I started with a gut admiration for the breadth of his playing and a confusion about his artistic and personal mores. Through the years of work I have read all the transcripts and seen the TY interviews. I have listened to him interpret his own life and work and diagnose his troubles. I have spoken to people close to him, people who lived with him, who have constantly alluded to a greater mystery than I imagined when I set out. I recall my initial preconceptions, and how they were upended as I went along. From the outset it has been a tangled skein: the friendless childhood (I found many friends), the apathy for life (I learnt about burning teenage passions), the wildness (I learnt of paralysing fears), the idolatry for Olivier and the National (abandoned), the adoration of America (out-distanced), the alcoholism (conquered), the despair and paranoia.

Tony Hopkins presented a prism of contradictions. The stagecraft, the voice quality, the genius for mimicry, the mystical presence, the popular appeal all of it was undeniably true. And yet every triumph, clich as it sounds, threw a shadow. For Hopkins, no moment seemed true enough, no peak high enough. All his friends, co-workers, actors and directors, from his first days at the YMCA in Port Talbot to his Hollywood heyday, speak of him as an actor of instinct. Yet, even out of alcoholism, his best instincts were frequently counter-balanced by appalling professional misjudgements. Victory at Entebbe, A Change of Seasons, Hollywood Wives effusions of vapid nonsense every bit as careless as the trash for which he privately castigated lesser actors. What was this self-checking mechanism that operated too in his private life, unbalancing him at moments of great domestic peace, precipitating crisis after crisis? A distortion of chance? Or more?