This book made available by the Internet Archive.

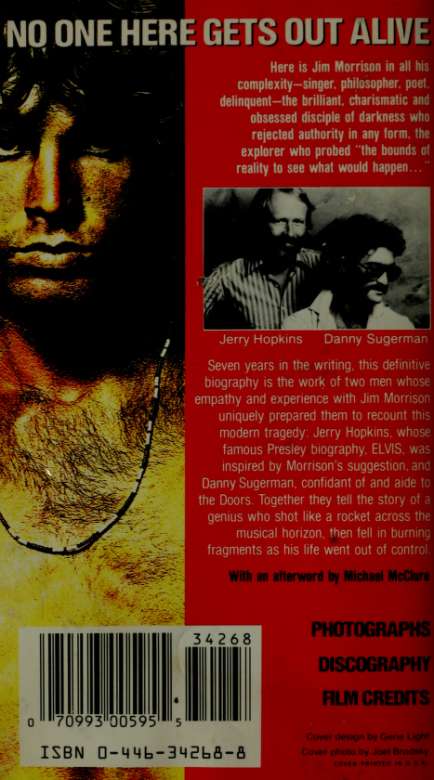

Jerry

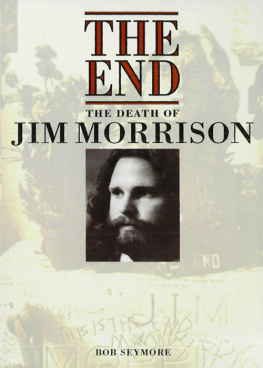

Ray &Jim

Danny

Let's just say I was testing the bounds of reality. I was curious to see what would happen. That's all it was: just curiosity.

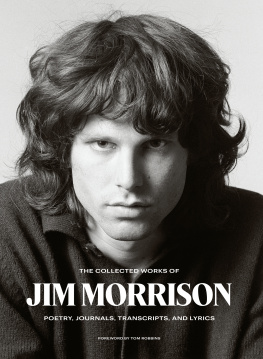

Jim Morrison Los Angeles, 1969

Foreword

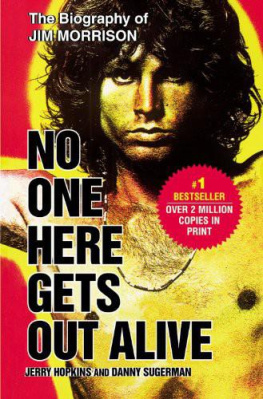

Jim Morrison was well on his way to becoming a mythic

hero while he was still alivehe was, few will dispute, a Hving legend. His death, shrouded in mystery and continuing speculation, completed the consecration, assuring him a place in the pantheon of wounded, gifted artists who felt life too intensely to bear living it: Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire, Lenny Bruce, Dylan Thomas, James Dean, Jimi Hendrix, and so on.

This book neither propels nor dispels the Morrison myth. It is simply a reminder that there is more to Jim Morrison (and the Doors) than legend; that the legend is founded in fact. Sometimes the content of this book is in sharp conflict with the myth, sometimes it is indistinguishable from it. Such was the man.

My personal beHef is that Jim Morrison was a god. To some of you, that may sound extravagant; to others, at least eccentric. Of course, Morrison insisted we were all gods and our destiny was of our own making. I just wanted to say I think Jim Morrison was a modem-day god. Oh hell, at least a lord.

Until now we have had httle understanding of the man.

[ Foreword ]

His work as a member of the Doors continues to reach new audiences, while the man's real talent and sources of inspiration are all but ignored. The stories of arrests and feats circulate wider and wilder than ever, while our image of the man himself g^ows dim.

Morrison changed my life. He changed Jerry Hopkins's life. The truth is Jim Morrison turned a lot of lives around, not only those that were in his immediate orbit, but those he reached as the controversial singer/lyricist of the Doors.

This book is the coverage of Jim's life, not his meaning. Yet we gain insight into the man simply by seeing where he came from and how he got where he was headed.

Getting hip to Morrison in the first place, back in 1967 (which was when most of us first heard from him), was no easy task. It involved more than a bit of soul searching; identifying with Jim meant you were an outsider who preferred to look in. Rock and roll has always attracted a lot of misfits with identity problems, but Morrison took being an outsider one step further. He said, in effect, "That's okay, we like it here. It hurts and it's hell, but it's also a helluva a lot more real than the trip I see you on." He pointed his finger at the parents, teachers, and the other authority figures around the land. He did not make vague references. Angered by the fraud, he did not implyhe blatantly, furiously accused. Then he showed us what it was really like: "People are strange when you're a stranger/ faces are ugly when you're alone." He showed us what could be: "We could be so good together/I'll ttll you about the world we'll invent/wanton world without lament/enterprise/ expedition/invitation and invention." He communicated with emotion, rage, grace, and wisdom. He offered very little in the way of compromise.

. Getting in was definitely not Jim's concern. Getting past or by was not Jim's concern. Jim's only motivation was to break through it all. He'd read about those others who had, and he believed it was possible. And he wanted to take us with him. "We will be inside the gates by evening," he sang. The first few magical years of the Doors' life were little more than [viii]

[ FOREWOKO ]

Jim and his band taking dieir audiences on abbreviated visits to another placea territory that transcended good and evil; a sensuous, dramatic musical landscape. Of course, the ultimate breakthrough to the other side is death.

You can straddle the fence between life and death, between "here" and "there," for only so long. Jim did it, frantically waving his arm for us to join him. Sadly, he seemed to need us more than we needed him. We surely were not ready for where he wanted to take us. We wanted to watch him and we wanted to follow, but we did not. We couldn't. And Jim couldn't stop. So he went on alone, without us.

Jim didn't want help. He only wanted to help. I do not believe Jim Morrison was ever on the "death trip" so many writers claimed he was on. I believe Jim's trip was about life. Not temporary life, but eternal bliss. If he had to kill himself to get there, or even to get a mite closer to his destination, that was all right. If there was any sadness at the end of Jim's life, it was the grief of instinctive, mortal clinging. But as a lord, as a visionary, he knew better.

The story you are about to read may sound like a tragedy, but for me it is a tale of liberation. No matter what depression and frustration Jim might have endured in his final days, I believe he also knew joy, hope, and the calm knowledge that he was almost home.

It does not matter how Jim died. Nor does it particularly matter that he left us so young. It is only important that Jim Morrison lived, and lived with the purpose birth proposes: to discover yourself and your own potential. He did that. Jim's short life speaks well. And I have already spoken too much.

There will never be another one like him.

Danny Sugerman

Beverly Hills, California March 22, 1979

The Bow

Is

Drawn

Chapter

o

nee, when the snow was packed high in the mountains outside Albuquerque, near San-dia Peak, Steve and Clara Morrison took their children tobogganing. Steve was stationed at nearby Kirtland Air Base where he was the executive officer and number two man at what was called the Naval Air Special Weapons Facility. That meant atomic energy, then still a mysterious subject and one he couldn't discuss at home.

It was the winter of 1955 and Jim Morrison was just a few weeks past his twelfth birthday. In less than a month his sister, Anne, who was turning into a chubby sort of tomboy, would be nine. His brother, Andy, somewhat huskier than Jim, was half his age.

The picture was winter simplicity: in the background the snowy Sangre de Cristo Mountains of New Mexico, in the foreground rosy cheeks, dark wavy hair almost hidden by warm-fitting hatshealthy children in heavy coats, clambering onto a wooden toboggan. No snow was falling, there were only the dry, stinging flurries blown by gusts of mountain wind.

[ No One Here Gets Out Auve ]

At the edge of the slope Jim placed Andy in the front of the sled. Anne got behind Andy, and Jim squeezed in at the rear. Using their mittened hands, they propelled themselves forward and slid away with a whoosh and whoop.

Faster and faster they went. In the distance, approaching rapidly, was a cabin.

Next page