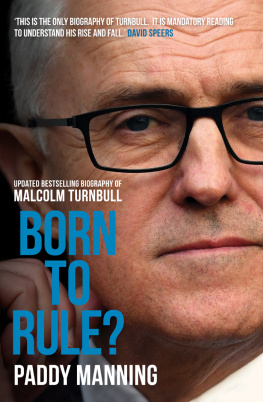

BORN TO RULE

For my father, Peter Manning, whose courageous and

independent journalism has been a lifelong inspiration.

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

1115 Argyle Place South, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2015

Text Paddy Manning, 2015

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2015

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Cover design by Philip Campbell Design

Typeset in Bembo 12/15pt by Cannon Typesetting

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the National Library of Australia

ISBN 9780522868807 (hbk)

ISBN 9780522868814 (ebook)

Contents

Prologue

I T WAS 7.10 AM on Thursday, 5 June 2014, and the airwaves hissed as Sydneys most powerful broadcaster, Alan Jones, worked himself up to his well-planned-and-executed ambush: Can I begin by asking you if you could say after me this? As a senior member of the Abbott government, I want to say here I am totally supportive of the AbbottHockey strategy for Budget repair.

A heartbeats silence. Then Malcolm Turnbull flashed cold steel: Alan, I am not going to take dictation from you.

An Oh escaped, barely audible. The Parrot, whod lectured the country for forty years, was rocking on his perch. Nobody spoke to Jones that way. Trying to regain his balance, Jones pecked and squawked, attacking every which way, trying to get the famously volatile communications minister to explode. In career-ending fashion, if possible. Radio gold. Australia tuned in:

Youre sounding very nervous, Malcolm Are you angry, Malcolm? Youre not much good at teams You have no hope ever of being the leader, youve got to get that into your head Youve got a few sensitive nerves there, Malcolm Youve got not a hope in hell of getting Tony Abbotts job

Sensing the danger, with unmistakeable effort, Turnbull channelled his rage: the more personal Jones got, the more lucid, and civil, and firm were Turnbulls replies. His low voice was a weapon, expertly drawn, the tone of a barrister, a newsman, a debating champ, an actors son.

In 2014, however, it was also the voice of a failed Liberal leader, and perhaps already that of a washed-up politician, who now had to put up with this.

Jones and Turnbull went way back, of course, and theyd spoken the night before, ticking off the bullet points, though no clues had been given of the mornings premeditated verbal assault. It was in keeping with their colourful history. Jones had disparaged Turnbull in 1981, during Turnbulls first tilt at the plush Sydney eastern suburbs seat of Wentworth. And he had launched a barrage against the republic campaign in 1999. But Jones had backed Turnbull for preselection in 2004, when it really mattered.

The issue that morningyes, Turnbull had dined with Clive Palmer, without telling his leaderwas not actually the heart of the matter. Jones wanted to try and convict Turnbull, once and for all, on the charge he was not really a Liberal.

The story of the dinner had been running since Palmer and Turnbull had been snapped leaving the Wild Duck restaurant in Canberra the previous Wednesday. Turnbull was supposed to have been at a Minerals Council dinner at Parliament House that night, where the PM was speaking, but had snuck off for dinner with Liberal Party vice-president Tom Harley. In the parliamentary car park, theyd bumped into Treasury secretary Martin Parkinsonwho had also left an empty chair at the mining dinner upstairsand asked him along. Turnbull then texted his old friend Palmer, and he too escaped the turgid resources love-in, joining the threesome after entrees.

When the photos came out, two weeks after the Abbott governments first Budget had tanked, there were days of fevered speculation about what might have been discussed over Peking duck and fried ricewashed down with some no-doubt-excellent wineby the deposed leader, the machine man, the shafted Treasury official, and

News Ltd columnist and Abbott supporter Andrew Bolt, interviewing the prime minister on his Sunday morning shout-fest, The Bolt Report, put it to Abbott straight: Malcolm Turnbull is after your job. Turnbull was incensedhe was being fitted-up as disloyaland called Abbott, who promised that Bolts question had not been planted by the prime ministers office, run by the powerful Peta Credlin, Turnbulls own former chief of staff, whom he had demoted when he was opposition leaderno love lost there. That evening, Bolt blogged that Turnbull had lavished a lot of charm lately on Abbotts natural predators, even last week launching a new parliamentary group of friends of the ABC, which got a (small) cut in the budget. Turnbull hit back:

It borders on the demented to string together a dinner with Clive Palmer and my attending as the communications minister the launch by a cross-party group of friends of the ABC and say that that amounts to some kind of threat or challenge to the prime minister. It is quite unhinged.

Abbott jetted off to France for the seventieth anniversary of D-day, leaving behind a mess. There was no leadership speculation less than a year into office, everyone agreed. But wasnt the Budget a stinker? Werent the polls terrible? Within days, an Essential poll confirmedonce againthat Turnbull was the peoples preferred Liberal leader, rating 31 per cent to Abbotts 18 per cent.

Wily old Palmer stirred the pot, launching a shameless attack on Credlin under the cover of parliamentary privilege, claiming she was behind Abbotts paid parental leave scheme: Why should

Turnbull texted Credlin, apologising for Palmer and offering to jump to Credlins defence: Chris Mitchell at The Australian had asked him to do an op-ed. Credlin, who had barely had any contact with Turnbull since Abbott had replaced him as Liberal leader in December 2009, replied: We are not that close. Id rather you didnt. Is Turnbull feeling guilty? she wondered. It all made sense. Clives ridiculous outburst must have started with Turnbull, over that dinner at Wild Duck, having a whinge about Tony, about the Budget, about PPL, about her. She pictured Turnbull tying it all together in a savage dump on the government.

When Alan Jones, well briefed as always, goaded Turnbull about Credlin, Turnbull oozed sensitivity: Alan, I dont want to make political capital out of Peta Credlins pain, other people do. Ive worked with Peta Credlin. She does a very good job for Tony and the nation, she does a tough job. This is really hurtful, personal stuff.

On it went. Turnbull checked Jones, parried him, even found humour, and by the end of the interview had him eating out of his hand. Well done! Jones said, and all but apologised for his old schoolmasters ruse. A polite goodbye, and a sharp clickTurnbull had managed to hang up on air. Then the volcanic anger that Turnbull had contained on air erupted in a roar of expletives.

It did die down. Turnbull was then four months shy of sixty. Come October, friends who had been to his thirtieth, fortieth and fiftieth birthday parties wondered where their invitations had gone. Turnbulls circle of acquaintances was peerlesshe could drop names on a global scalebut his circle of trusted friends was getting smaller and smaller. In fact, instead of a birthday party, Turnbull had a quiet drink in the office of the prime minister. Abbott was feeling magnanimous towards the man he had torn down in 2009. Malcolm simply was no longer a threat, it seemed, merely a loyal member of the government. Cabinet colleagues who didnt even like him noted an air of resignation in Turnbull. Perhaps he might be ready for promotion to treasurer, given the federal Budget was proving unsaleable. Then again, perhaps not.

Next page