Campaign 85

Peking 1900

The Boxer Rebellion

Peter Harrington Illustrated by Alan & Michael Perry

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

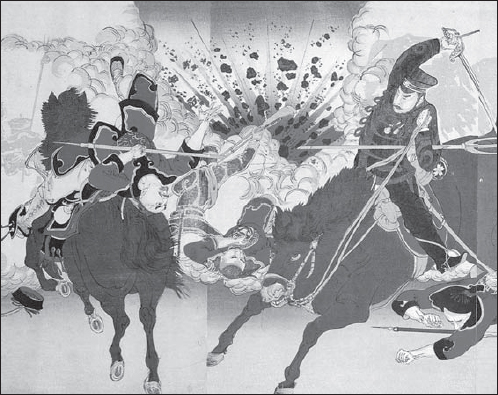

The last stand of the Chinese at Langfang drawn by Frank Craig from a sketch by a British naval officer, and published in theGraphicon 25 August 1900. According to the officer who made the sketch, the train carrying around 900 British and Germans was attacked as it was going down to Yangtsun. The fighting lasted two hours and the scene shows Chinese troops trying unsuccessfully to save their banner. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

BACKGROUND TO THE SIEGE OF PEKING

S imply put, the Boxer outbreak in North China in the summer of 1900 can be attributed directly to Chinese hatred of foreigners and foreign interference in their country. While there were other reasons for the revolt such as economic hardships brought on by poor harvests, floods and drought, they were all blamed on the foreign devils who were encroaching on China in increasing numbers. In short, the Boxer Rebellion was a last gasp attempt to throw off the foreign yoke and preserve the Chinese culture, religion and way of life once and for all.

While the immediate causes can be traced to various events in 1898 and 1899, these were merely a culmination of over 60 years of Chinese frustration of mounting foreign interference in their country. Following the Napoleonic Wars, the victorious nations were looking to expand their foreign markets through the acquisition of foreign lands, a phenomenon that would only end with the First World War. Britain in particular looked towards China as an untapped resource worth exploiting and fought two wars between 1839 and 1860 in order to secure a foothold in the vast country. The first conflict, known today as the Opium War, lasted from 1839 until 1842 and was the result of disagreements between Chinese officials and British merchants in the port of Canton particularly concerning the supply of opium from India. Success was achieved by British forces with the capture of Shanghai and Chinkiangfoo in the summer of 1842 resulting in the Treaty of Nanking, in which Hong Kong was ceded to Britain, a war indemnity of $20 million was levied on the defeated, and various Chinese ports were opened up to British trade. Seventeen years later, a combined Anglo-French force attacked the Taku (Dagu) Forts at the mouth of the Peiho (Baihe) River in order to force the Chinese emperor to grant further trade concessions. Peking (Beijing) was entered by allied forces on 12 October 1860.

The Chinese encampment in the North Fort at Taku on the Peiho River photographed in 1860. On 25 June 1860, the British bombarded the forts at Taku but landing parties were beaten back with heavy casualties. Two months later following a short bombardment, the North Fort was stormed by British and French troops, and the other forts quickly surrendered. Peking was entered on 12 October 1860. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

French soldiers fighting Chinese on a bridge during the Tonkin War of 1884, in a drawing by E. Bouard. France had been trying to establish a colony in Indochina (present-day Vietnam) since the Anglo-French campaign against China in 1860. China regarded the region as her own and fought a number of small wars to try to repel the French. The latter scored a major victory over the Chinese at Son-Tay in December 1883. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

In the wake of the European military victories and the economic opportunities which they brought, came merchants and businessmen, arms dealers and engineers, missionaries and concessionaires, advisers and an odd assortment of unsavoury characters eager to make money at the expence of the Chinese. Both sides viewed the other with contempt, the Chinese poking fun at the physical characteristics of the Europeans such as their red hair and large noses, the Europeans seeing the Chinese as backward, racially inferior, and proof of Darwinian theories regarding the supremacy of the white race. The two sides did not mix well and the Europeans who moved into China created little enclaves where they lived apart from the Chinese. A few scholars and intellectuals tried to understand the natives by adapting to their dress and customs but the Chinese held them in contempt. The Catholic and Protestant churches felt it was their duty to civilise the Chinese by introducing them to the Bible and the words of Jesus; and while they had some success in converting the local populations, most Chinese were highly cynical towards the Christian religion and ridiculed it. Both sides displayed absolute ignorance towards the other. Chinese reaction towards the foreigners took various forms, from violence and terrorism to passive resistance and xenophobic literature such as a publication entitled The Death Blow to Corrupt Doctrines in which the author poked fun at the Europeans in a derogatory fashion.

ANTI-FOREIGN RIOTS

It was in the southern provinces that the first anti-foreign incidents occurred during the decade 1886 to 1896. Earlier in 1875 a westerner had been murdered in Yunnan but it was the foreign presence in the south after 1884 which brought about the first significant developments. France had extended its empire into Tonkin by military conquest and the British were on Chinas border in Burma, and through a series of treaties both were allowed to build railways in China, obtain mining concessions, open up routes and create trading stations. In the wake of the traders and businessmen were the missionaries. It was too much for the Chinese at Chungkung in Szechuan Province who destroyed the British consulate and other foreign buildings in July 1886. Three years later the foreign concession and consulates at Chinkiang were plundered and ruined by a Chinese mob. Next it was the turn of Hankow, where a riot led by students was swiftly put down, but these were just the beginning of a rapidly spreading movement which now began to attack Christian sites. A French Catholic orphanage was assailed but saved by French officials, and in May and June 1891 there were uprisings along the Yangtse River resulting in the death of several British citizens. While some of these attacks may have been spontaneous outpourings of Chinese hatred towards foreigners, there is evidence that some secret societies such as the anti-government Kao Lao Hui carried out attacks on missionaries hoping to embarrass the Manchus in Peking and bring about their fall. To many Chinese the Manchus were viewed as foreign usurpers non-Chinese people from beyond the Great Wall who had conquered China as far back as 1644; they were to rule the country until their overthrow in 1912.

The overall impact of these disturbances was slight but they brought about a marked shift in the policies of the western powers who built up significant naval forces to patrol the region in the early 1890s at the same time making it very clear that they would not tolerate any further outrages committed against their citizens. Nonetheless, serious anti-foreign outbreaks occurred especially in the north, which up till then had been relatively immune from foreign incursions. Furthermore, in 1895 the various western missionary organisations made a concerted effort to bring the message to every Chinese, an act viewed by many as a portent of worse things to come.