The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Pierette Simpson, whose devotion to the Andrea Dorias memory and generosity helped make this book possible

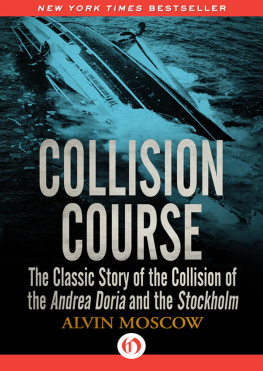

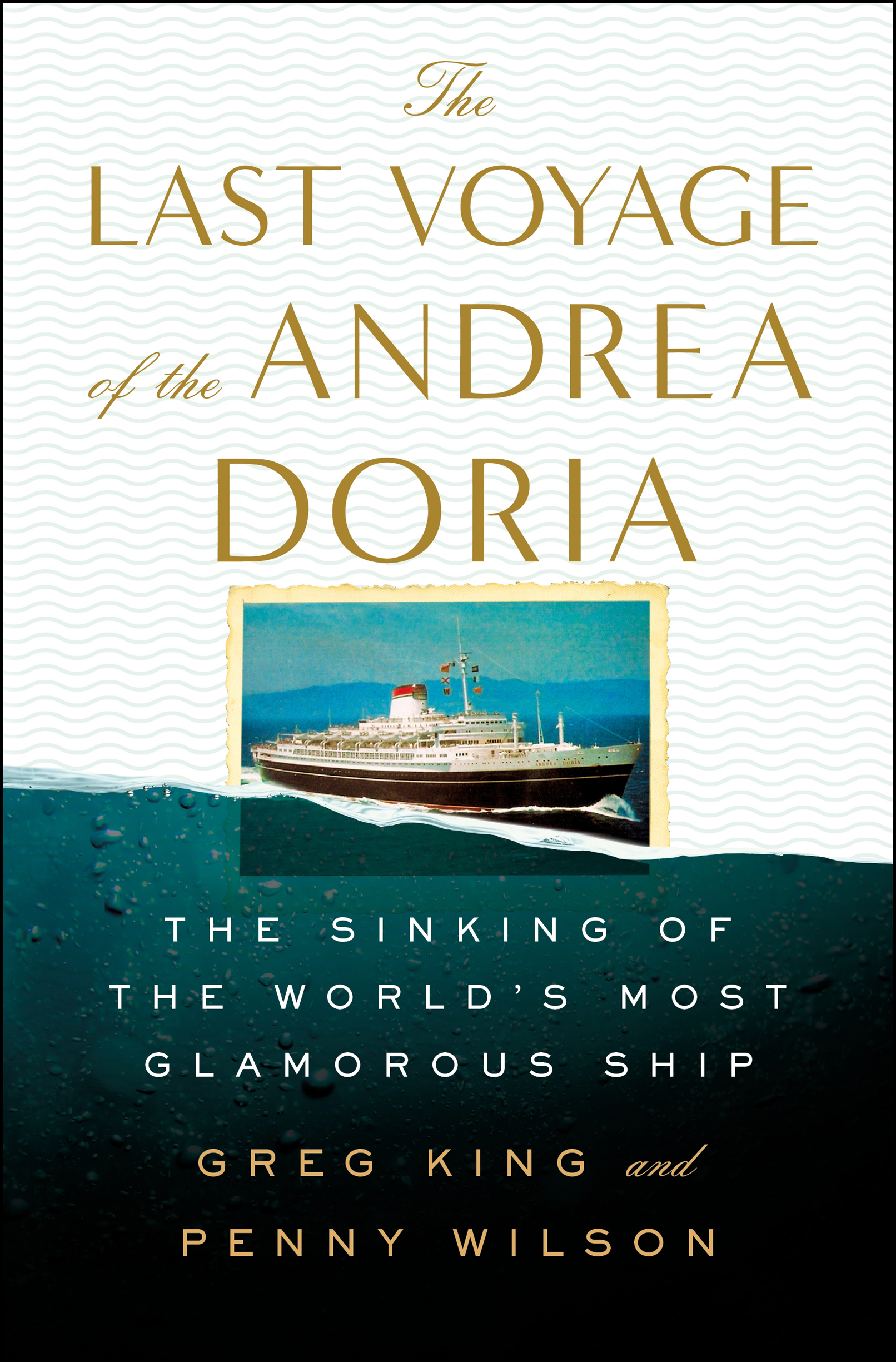

In the summer of 1956, readers were captivated by Walter Lords A Night to Remember, which chronicled the sinking of the magnificent Titanic on her maiden voyage to New York in April 1912. As the story of the impossibly splendid, doomed Titanic took the world by storm, another liner prepared to set sail from its berth in the bustling port of Genoa. Andrea Doria was so famous for her beauty and luxurious onboard life that many people diverted travel plans from other vessels and even airplanes to book passage on this wonderful and happy ship.

The proud flagship of the Italian Line, Andrea Doria represented not only the nations postwar recovery but also its glamorous, creative, and artistic march toward modernity. A living testament to the importance of beauty in the everyday world was how the Italian Line described the Doria on her maiden voyage in 1953. Her seven-hundred-foot-long sleek hull, shimmering black and topped by a cascade of white decks, was somehow traditional while still looking to the future. Previous liners had sported elaborately paneled rooms crowned with stained glass domes and crowded with opulent, overstuffed furniture modeled on British country house interiors. The Doria was starkly different: her modern roomsall concealed lighting, wooden veneers, aluminum strips, and boldly colored, angular furniturecaused a sensation. The cutting-edge dcor and oceangoing Italian hospitality drew a diverse contingent of passengers to this voyage, representing a true microcosm of the twentieth century: aristocrats and heiresses; actors and ballet stars; celebrity politicians and media moguls; a burgeoning rock-and-roll musician and American tourists hoping to indulge in la dolce vita; and immigrants reluctantly leaving their villages to seek new lives in the United States.

It was ironic that so many of the passengers on this trip, the Dorias 101st Atlantic crossing, carried copies of A Night to Remember to their cabins, setting them on bedside tables or tucking them beneath pillows in anticipation of cracking open the spine and enjoying the story of Titanic. Not one seems to have worried that reading about a maritime disaster while at sea might result in an inadvertent but ominous sense of dj vu. That first night, and all the days and nights that followed, the Dorias passengers, snug in their berths or reposing on sun-drenched deck chairs, knew that they were quite safe from Titanics fate. It was summer; the Doria traveled an iceberg-free southern route; and radar and modern technologies seemingly ensured safety at sea.

And then, on the morning of July 26, people turned on their television sets to stunning news. The previous night, the Swedish liner Stockholm had rammed the Doria just off Nantucket. The images were shocking, stark, unbelievable: the great liner on her side in the Atlantic, abandoned as the ocean slowly but surely took possession. It was the first time that a maritime tragedy had played out before millions of eyes. Over the next few days, viewers saw heartrending scenes of survivors arriving in New York as they pushed past cameras and microphones for emotional reunions with desperate relatives. There were tales of heroism and allegations of cowardice, of joy and of loss, and, above all, a sense of disbelief that a tragedy like that which had befallen Titanic could occur in the modern age. But icebergs, as Dorias passengers had discovered, could take many shapes.

In 1956 there would be no Titanic-like casualty figures. Thanks to the valiant efforts of the Andrea Dorias captain and crew, as well as heroic actions by a handful of ships like the French liner Ile de France that had raced to the scene of the collision, only fifty-one lives were lost. Ten were children aboard Andrea Doria, their lives tragically cut short; speaking to their surviving siblings today, the pain remains sharp, the loss incalculable, their memories undimmed by the passage of time.

Arrogance played a part in the Titanic disaster, but Andrea Doria had done nothing to tempt fate. From the gracious and paternal captain to his competent officers to the smiling and helpful employees of the ships hotel, the passengers had discovered a world of peace and quiet, recreation and reflection, art, entertainment, and new friendsa place to spend an enjoyable week away from the pressures of everyday life until, contented and recharged, they were delivered safely to their destination port. The fact that this expected happy ending to the voyage was torn away from those on the Doria less than twelve hours before they were due to dock in New York made the tragedy all the more poignant.

After a century of books, films, and musicals, Titanic remains maritime historys best-known disaster. Yet Andrea Dorias story is more immediate. Many vividly recall watching footage of the sinking and the emotional reunions as survivors arrived in New York. The Doria is closer in time to us than Titanic, and many of her survivors are still alive today. From girls in sundresses sliding down rough ropes into lifeboats, to a young boy venturing into the lower decks of the ship to retrieve his sleeping little sister from their cabin, survivors of the Andrea Doria confronted danger with great bravery and fortitude. Their stories are inspiring, dramatic, and occasionally tragic and deserve to be better known.

The Andrea Doria disaster did not deliver a death blow to the liner industry: it was the increase in commercial air flights that did that. But looking back, it is impossible not to read her tragic death as the foreshadowing of a future already being written in vapor trails against the sky even as her hull disappeared beneath the waves.

At nine oclock on the evening of Monday, April 16, 1956, millions of Americans tuned in to CBS to watch the latest episode of the hit comedy I Love Lucy. Since January, viewers had followed the madcap adventures of the Ricardos and their friends the Mertzes on a trip to Europe. After episodes set in London, Scotland, and Paris, Lucille Ball and company moved on to Italy. That Monday nights episode, Lucys Italian Movie, had the comedienne preparing for a role in a fictional film called Bitter Grapes by stomping her way through a vat of fruit at a local vineyard and ending in a riotous brawl that became one of the most celebrated moments in the series.

Lucys Italian Movie cemented the shift in American attitudes toward the former World War II enemy. After liberating Naples and Rome, soldiers had returned to the United States with memories of sun-drenched piazzas and endless feasts of pasta washed down by flowing wine; a fair number also returned with brides who were surprised to find an America enraptured with pizza and entertainers like Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, and Dean Martin. They flocked to movies by Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica and witnessed the rise of Italian stars like Anna Magnani, Gina Lollabrigida, and the sultry Sophia Loren, who flaunted her affair with married director Carlo Ponti.